On the physical origins of modern AI – an explainer on the 2024 Nobel for physics

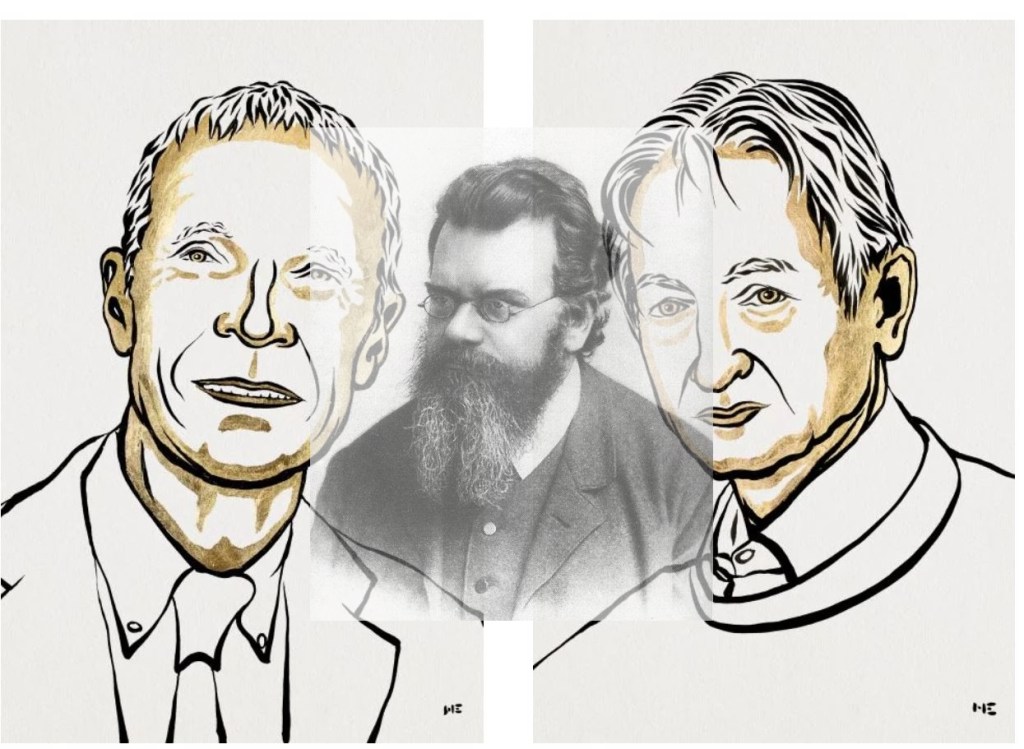

My first reaction when I heard that John Hopfield and Geoffrey Hinton had been awarded the Physics Nobel was – “aren’t there any advances in physics that are, perhaps, more deserving?” However, after a bit of reflection, I realised that this was a canny move on part of the Swedish Academy because it draws attention to the fact that some of the inspiration for the advances in modern AI came from physics. My aim in this post is to illustrate this point by discussing (at a largely non-technical level) two early papers by the laureates which are referred to in the Nobel press release.

The first paper is “Neural networks and physical systems with emergent collective computational abilities“, published by John Hopfield in 1982 and the second is entitled, “A Learning Algorithm for Boltzmann Machines,” published by David Ackley, Geoffrey Hinton and Terrence Sejnowski in 1985.

–x–

Some context to begin with: in the early 1980s, new evidence on the brain architecture had led to a revived interest in neural networks, which were first proposed by Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts in this paper in the early 1940s! Specifically, researchers realised that, like brains, neural networks could potentially be used to encode knowledge via weights in connections between neurons. The search was on for models / algorithms that demonstrated this. The papers by Hopfield and Hinton described models which could encode patterns that could be recalled, even when prompted with imperfect or incomplete examples.

Before describing the papers, a few words on their connection to physics:

Both papers draw on the broad field of Statistical Mechanics, a branch of physics that attempts to derive macroscopic properties of objects such as temperature and pressure from the motion of particles (atoms, molecules) that constitute them.

The essence of statistical mechanics lies in the empirically observed fact that large collections of molecules, when subjected to the same external conditions, tend to display the same macroscopic properties. This, despite the fact the individual molecules are moving about at random speeds and in random directions. James Clerk Maxwell and Ludwig Boltzmann derived the mathematical equation that describes the fraction of particles that have a given speed for the special case of an ideal gas – i.e., a gas in which there are no forces between molecules. The equation can be used to derive macroscopic properties such as the total energy, pressure etc.

Other familiar macroscopic properties such as magnetism or the vortex patterns in fluid flow can (in principle) also be derived from microscopic considerations. The key point here is that the collective properties (such as pressure or magnetism) are insensitive to microscopic details of what is going in the system.

With that said about the physics connection, let’s move on to the papers.

–x–

In the introduction to his paper Hopfield poses the following question:

“…physical systems made from a large number of simple elements, interactions among large numbers of elementary components yield collective phenomena such as the stable magnetic orientations and domains in a magnetic system or the vortex patterns in fluid flow. Do analogous collective phenomena in a system of simple interacting neurons have useful “computational” correlates?”

The inspired analogy between molecules and neurons led him to propose the mathematical model behind what are now called Hopfield Networks (which are cited in the Nobel press release). Analogous to the insensitivity of the macroscopic properties of gases to the microscopic dynamics of molecules, he demonstrated that a neural network in which each neuron has simple properties can display stable collective computational properties. In particular the network model he constructed displayed persistent “memories” that could be reconstructed from smaller parts of the network. As Hopfield noted in the conclusion to the paper:

“In the model network each “neuron” has elementary properties, and the network has little structure. Nonetheless, collective computational properties spontaneously arose. Memories are retained as stable entities or Gestalts and can be correctly recalled from any reasonably sized subpart. Ambiguities are resolved on a statistical basis. Some capacity for generalization is present, and time ordering of memories can also be encoded.”

–x–

Hinton’s paper, which followed Hopfield’s by a couple of years, describes a network “that is capable of learning the underlying constraints that characterize a domain simply by being shown examples from the domain.” Their network model, which they christened “Boltzmann Machine” for reasons I’ll explain shortly, could (much like Hopfield’s model) reconstruct a pattern from a part thereof. In their words:

“The network modifies the strengths of its connections so as to construct an internal generative model that produces examples with the same probability distribution as the examples it is shown. Then, when shown any particular example, the network can “interpret” it by finding values of the variables in the internal model that would generate the example. When shown a partial example, the network can complete it by finding internal variable values that generate the partial example and using them to generate the remainder.”

They developed a learning algorithm that could encode the (constraints implicit in a) pattern via the connection strengths between neurons in the network. The algorithm worked but converged very slowly. This limitation is what led Hinton to later invent Restricted Boltzmann Machines, but that’s another story.

Ok, so why the reference to Boltzmann? The algorithm (both the original and restricted versions) uses the well-known gradient descent method to minimise an objective function, which in this case is an expression for energy. Students of calculus will know that gradient descent is prone to getting stuck in local minima. The usual way to get out of these minima is to take occasional random jumps to higher values of the objective function. The decision rule Hinton and Co use to determine whether or not to make the jump is such that the overall probabilities of the two states converges to a Boltzmann distribution (different from, but related to, the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution mentioned earlier). It turns out that the Boltzmann distribution is central to statistical mechanics, but it would take me too far afield to go into that here.

–x–

Hopfield networks and Boltzmann machines may seem far removed from today’s neural networks. However, it is important to keep in mind that they heralded a renaissance in connectionist approaches to AI after a relatively lean period in the 1960s and 70s. Moreover, vestiges of the ideas implemented in these pioneering models can be seen in some popular architectures today ranging from autoencoders to recurrent neural networks (RNNs).

That’s a good note to wrap up on, but a few points before I sign off:

Firstly, a somewhat trivial matter: it is simply not true that physics Nobels have not been awarded for applied work in the past. A couple of cases in point are the 1909 prize awarded to Marconi and Braun for the invention of wireless telegraphy, and the 1956 prize to Shockley, Bardeen and Brattain for the discovery of the transistor effect, the basis of the chip technology that powers AI today.

Secondly: the Nobel committee, contrary to showing symptoms of “AI envy”, are actually drawing public attention to the fact that the practice of science, at its best, does not pay heed to the artificial disciplinary boundaries that puny minds often impose on it.

Finally, a much broader and important point: inspiration for advances in science often come from finding analogies between unrelated phenomena. Hopfield and Hinton’s works are not rare cases. Indeed, the history of science is rife with examples of analogical reasoning that led to paradigm-defining advances.

–x–x–

[…] Aside 2: Interestingly, the Roseblueth-Wiener-Bigelow paper along with this paper by Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts laid the foundation for cybernetics. A little known fact is that the McCulloch-Pitts paper articulated the basic ideas behind today’s neural networks and Nobel Prize glory, but that’s another story. […]

LikeLike

On the anticipation of unintended consequences | Eight to Late

February 18, 2025 at 5:23 am