Archive for November 2024

Towards a public understanding of AI – notes from an introductory class for a general audience

There is a dearth of courses for the general public on AI. To address this gap, I ran a 3-hour course entitled “AI – A General Introduction” on November 4th at the Workers Education Association (WEA) office in Sydney. My intention was to introduce attendees to modern AI via a historical and cultural route, from its mystic 13th century origins to the present day. In this article I describe the content of the session, offering some pointers for those who would like to run similar courses.

–x–

First some general remarks about the session:

- The course was sold out well ahead of time – there is clearly demand for such offerings.

- Although many attendees had used ChatGPT or other similar products, none had much of an idea of how they worked or what they are good (and not so good) for.

- The session was very interactive with lots of questions. Attendees were particularly concerned about social implications of AI (job losses, medical applications, regulation).

- Most attendees did not have a technical background. However, judging from their questions and feedback, it seems that most of them were able to follow the material.

The biggest challenge in designing a course for the public is the question of prior knowledge – what one can reasonably assume the audience already knows. When asked this question, my contact at WEA said I could safely assume that most attendees would have a reasonable familiarity with western literature, history and even some philosophy, but would be less au fait with science and tech. Based on this, I decided to frame my course as a historical / cultural introduction to AI.

–x–

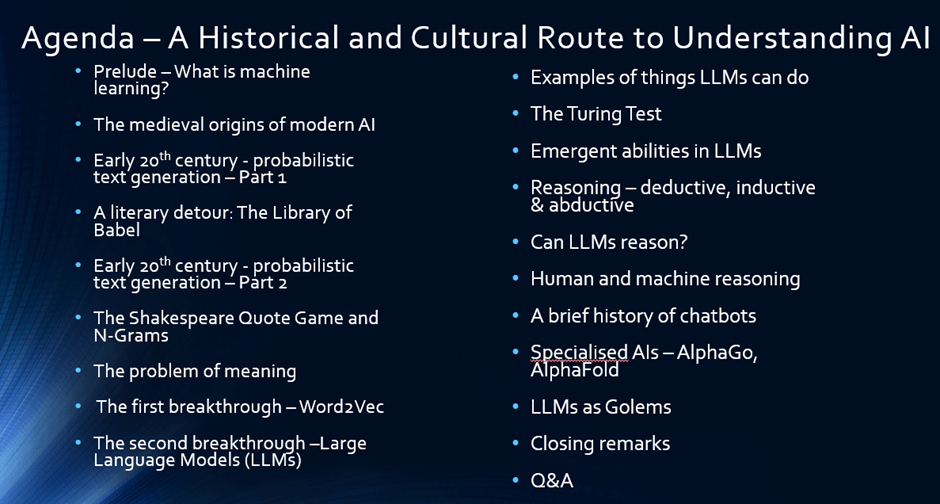

The screenshot below, taken from my slide pack, shows the outline of the course

Here is a walkthrough the agenda, with notes and links to sources:

- I start with a brief introduction to machine learning, drawing largely on the first section of this post.

- The historical sections, which are scattered across the agenda (see figure above), are based on this six part series on the history of natural language processing (NLP) supplemented by material from other sources.

- The history starts with the Jewish mystic Abraham Abulafia and his quest for divine incantations by combining various sacred words. I also introduce the myth of the golem as a metaphor for the double-edgedness of technology, mentioning that I will revisit it at the end of the lecture in the context of AI ethics.

- To introduce the idea of text generation, I use the naïve approach of generating text by randomly combining symbols (alphabet, basic punctuation and spaces), and then demonstrate the futility of this approach using Jorge Luis Borges famous short story, The Library of Babel.

- This naturally leads to more principled approaches based on the actual occurrence of words in text. Here I discuss the pioneering work of Markov and Shannon.

- I then use a “Shakespeare Quote Game” to illustrate the ideas behind next word completion using n-grams. I start with the first word of a Shakespeare quote and ask the audience to guess the quote. With just one word, it is difficult to figure out. However, as I give them more and more consecutive words, the quote becomes more apparent.

- I then illustrate the limitations of n-grams by pointing out the problem of meaning – specifically, the issues associated with synonymy and polysemy. This naturally leads on to Word2Vec, which I describe by illustrating the key idea of how rolling context windows over large corpuses leads to a resolution of the problem. The basic idea here is that instead of defining the meaning of words, we simply consider multiple contexts in which they occur. If done over large and diverse corpuses, this approach can lead to an implicit “understanding” of the meanings of words.

- I also explain the ideas behind word embeddings and vectors using a simple 3d example. Then using vectors, I provide illustrative examples of how the word2vec algorithm captures grammatical and semantic relationships (e.g., country/capital and comparative-superlative forms).

- From word2vec, I segue to transformers and Large Language Models (LLMs) using a hand-wavy discussion. The point here is not so much the algorithm, but how it is (in many ways) a logical extension of the ideas used in early word embedding models. Here I draw heavily on Stephen Wolfram’s excellent essay on ChatGPT.

- I then provide some examples of “good” uses of LLMs – specifically for ideation, explanation and a couple of examples of how I use it in my teaching.

- Any AI course pitched to a general audience must deal with the question of intelligence – what it is, how to determine whether a machine is intelligent etc. To do this, I draw on Alan Turing’s 1950 paper in which he proposes his eponymous test. I illustrate how well LLMs do on the test and ask the question – does this mean LLMs are intelligent? This provokes some debate.

- Instead of answering the question, I suggest that it might be more worthwhile to see if LLMs can display behaviours that one would expect from intelligent beings – for example, the ability to combine different skills or to solve puzzles / math problems using reasoning (see this post for examples of these). Before dealing with the latter, I provide a brief introduction to deductive, inductive and abductive reasoning using examples from popular literature.

- I leave the question of whether LLMs can reason or not unanswered, but I point to a number of different approaches that are popularly used to demonstrate reasoning capabilities of LLMs – e.g. chain of thought prompting. I also make the point that the response obtained from LLMs is heavily dependent on the prompt, and that in many ways, an LLM’s response is a reflection of the intelligence of the user, a point made very nicely by Terrence Sejnowski in this paper.

- The question of whether LLMs can reason is also related to whether we humans think in language. I point out that recent research suggests that we use language to communicate our thinking, but not to think (more on this point here). This poses an interesting question which Cormac McCarthy explored in this article.

- I follow this with a short history of chatbots starting from Eliza to Tay and then to ChatGPT. This material is a bit out of sequence, but I could not find a better place to put it. My discussion draws on the IEEE history mentioned at the start of this section complemented with other sources.

- For completeness, I discuss a couple of specialised AIs – specifically AlphaFold and AlphaGo. My discussion of AlphaFold starts with a brief explanation of the protein folding problem and its significance. I then explain how AlphaFold solved this problem. For AlphaGo, I briefly describe the game of Go, why its considered far more challenging than chess. This is followed by high level explanation of how AlphaGo works. I close this section with a recommendation to watch the brilliant AlphaGo documentary.

- To close, I loop back to where I started – the age old human fascination with creating machines in our own image. The golem myth has a long history which some scholars have traced back to the bible. Today we are a step closer to achieving what medieval mystics yearned for, but it seems we don’t quite know how to deal with the consequences.

I sign off with some open questions around ethics and regulation – areas that are still wide open – as well as some speculations on what comes next, emphasising that I have no crystal ball!

–x–

A couple of points to close this piece.

There was a particularly interesting question from an attendee about whether AI can help solve some of the thorny dilemmas humankind faces today. My response was that these challenges are socially complex – i.e., different groups see these problems differently – so they lack a commonly agreed framing. Consequently, AI is unlikely to be of much help in addressing these challenges. For more on dealing with socially complex or ambiguous problems, see this post and the paper it is based on.

Finally, I’m sure some readers may be wondering how well this approach works. Here are some excerpts from emails I received from few of the attendees:

“What a fascinating three hours with you that was last week. I very much look forward to attending your future talks.”

“I would like to particularly thank you for the AI course that you presented. I found it very informative and very well presented. Look forward to hearing about any further courses in the future.”

“Thank you very much for a stimulating – albeit whirlwind – introduction to the dimensions of artificial intelligence.”

“I very much enjoyed the course. Well worthwhile for me.”

So, yes, I think it worked well and am looking forward to offering it again in 2025.

–x–x–

Copyright Notice: the course design described in this article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/)