Archive for the ‘Business Fables’ Category

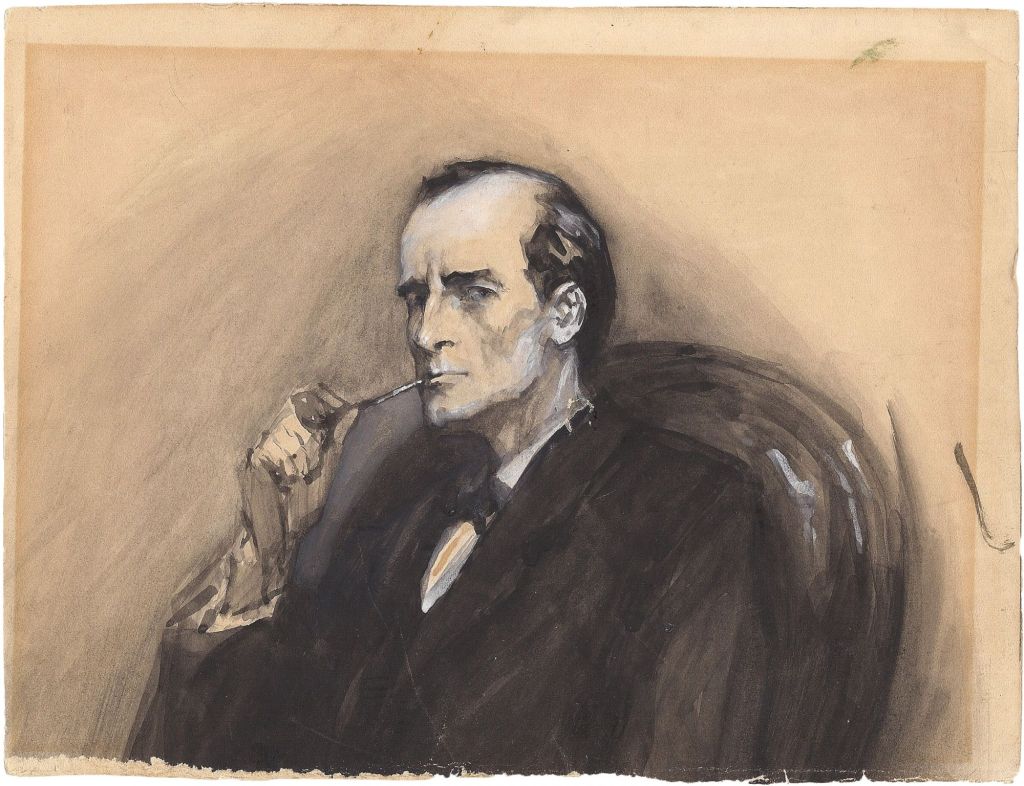

Sherlock Holmes and the case of the Agile rituals

As readers of these chronicles will know, the ebb in demand for the services of private detectives had forced Mr. Holmes to deploy his considerable intellectual powers in the service of large multinationals. Yet, despite many successes, he remained ambivalent about the change.

As he once remarked to me, “the criminal mind is easier to analyse than that of the average executive: the former displays a clarity of thought that tends to be largely absent in the latter.”

Harsh words, perhaps, but judging from the muddle-headed thinking I have witnessed in the corporate world, I think his assessment is fair.

The matter of the Agile rituals is a case in point.

–x–

It was a crisp autumn morning. I had risen at the crack of dawn and gone for my customary constitutional. As I opened the door to 221B on my return, I was greeted by the unmistakable aroma of cooked eggs and bacon. Holmes, who is usually very late in the mornings, save upon those not infrequent occasions when he is up all night, was seated at the table, tucking into an English Breakfast.

“Should you be eating that?” I queried, as I hung my coat on the rack.

“You underestimate the Classic English Breakfast,” he said, waving a fork in my direction. “Yes, its nutritional benefits are overstated, but the true value of the repast lies in the ritual of cooking and consuming it.”

“The ritual?? I was under the impression that rituals have more to do with the church than the kitchen.”

“Ah, Watson, you are mistaken. Practically every aspect of human life has its rituals, whether it be dressing up for work or even doing work. Any activity that follows a set sequence of steps can become a ritual – by which I mean something that can be done without conscious thought.”

“But, is not that an invitation for disaster? If one does not think about what one is doing, one will almost certainly make errors.”

“Precisely,” he replied, “and that is the paradox of ritualisation. There are certain activities that are safe to ritualise, so to speak. Preparing and partaking this spread, for example. It offers the comfort of doing something familiar and enjoyable – and there is no downside, barring a clogged capillary or two. The problem is that there are other activities that, when ritualised, turn out to be downright dangerous.”

“For example?” I was intrigued.

He smiled. “For that I shall ask you to wait until we go to BigCorp’s offices later today.”

“BigCorp??”

“So many questions, Watson. Come with me and all will be clear.”

–x–

We were seated in Jarvis’ office. He was BigCorp’s Head of Technology.

“Mr. Holmes, I was surprised to get your call this morning,” said Jarvis. “You were on site this Monday so I thought it would be at least a few more weeks before we heard from you. Doesn’t it take time to analyse all the information you collected from our teams? From what I was told you took away reams of transcripts and project plans.”

“Not all data is information, most of it is noise,” replied Holmes. “It is of the highest importance, therefore, not to have useless facts elbowing out the useful ones.”

“I see,” said Jarvis. The look on his face said he clearly didn’t.

“Let me get straight to the point,” said Holmes. “BigCorp implemented XXXX Agile framework across the organisation a year ago with the expectation it would improve customer satisfaction with projects delivered. In particular, the intent was to follow Agile Principles. So, you adapted and implemented Agile practices from XXXX that would enable you to operationalise the principles. Would that be a fair summary?” (Editor’s note: the name of the framework has been redacted at Mr. Holmes’ request)

“Yes, that is correct,” nodded Jarvis.

“My conversations with your staff make it clear that the practices and processes have indeed been adapted and implemented. And this has been confirmed by the many project documents I checked,” said Holmes.

“So, where’s the problem then?” queried Jarvis.

“Adopting a practice or process is no guarantee that it will be implemented correctly.” said Holmes.

“I’m not sure I understand.”

“It seems that your staff follow Agile practices ritualistically with no thought about the intent behind them. For example, stand up meetings are treated as forums to enforce specific points of view rather than debate them. Instead of surfacing issues and dealing with them in a way that works for all parties, the meetings invariably end up with winners and losers. This is totally counter to the Agile philosophy. As an observer, it seemed to me that there was no sense of ‘being in it together’ or wanting to get the best outcome for the customer.”

“How many meetings did you attend, Mr. Holmes?””

“Three.”

“Surely that is too small a sample to generalise from,” said Jarvis.

“Not if you know what to look for. You know my method. It is founded upon the observation of trifles. Things such as attitude, tone of voice, engagement, empathy etc. Believe me, I saw enough to tell me what is wrong. Your people have implemented practices but not the intent behind them.”

“I’m not sure I understand.”

“OK, an example might help. One of the Agile principles states that changing requirements are welcomed, even late in development. In one of the meetings I attended, the PM shut down a discussion about changes that the customer wanted by offering technical excuses. The conversation was used to enforce a viewpoint that is centred on BigCorp’s interests rather than those of the customer. Is that not counter to Agile principles? Surely, even if the customer is asking for something unreasonable, it is incumbent on your team to work towards mutual agreement rather than shutting them down summarily.”

“Hmm, I see. So, what do you recommend, Mr. Holmes?”

“You are not going to like what I say, Mr. Jarvis, but the fault lies with you and your management team. You have created an environment that is not conducive to the mindset and dispositions required to be truly Agile. As a result, what you have are its rituals, followed mindlessly. Only you can change that.”

“How?”

“By creating an environment that encourages your staff to develop an Agile mindset without fear of failure. I can recommend a reference or two.”

“That would be helpful Mr. Holmes,” said Jarvis.

Holmes elaborated on the reference and what Jarvis and his team needed to do. The conversation then moved on to other matters that are not relevant to my tale.

–x–

“That was excellent, Holmes,” I remarked, as we made our way out of the BigCorp Office.

“No, it’s elementary,” he replied with a smile, “it is simply that many practitioners prefer not to think about what it means to be Agile. Blindly enacting its rituals is so much easier.”

–x–

Notes:

- There are three quotes taken from Sherlock Holmes stories in the above piece. Can you spot them? (Hint: they are not in the last section.)

- See this post for more on rituals in information system design and development.

- And finally, for a detailed discussion of an approach that privileges intent over process, check out my book on data science strategy.

The story before the story – a data science fable

It is well-known that data-driven stories are a great way to convey results of data science initiatives. What is perhaps not as well-known is that data science projects often have to begin with stories too. Without this “story before the story” there will be no project, no results and no data-driven stories to tell….

For those who prefer to read, here’s a transcript of the video in full:

In the beginning there is no data, let alone results…but there are ideas. So, long before we tell stories about data or results, we have to tell stories about our ideas. The aim of these stories is to get people to care about our ideas as much as we do and, more important, invest in them. Without their interest or investment there will be no results and no further stories to tell.

So one of the first things one has to do is craft a story about the idea…or the story before the story.

Once upon a time there was a CRM system. The system captured every customer interaction that occurred, whether it was by phone, email or face to face conversation. Many quantitative details of interactions were recorded, time, duration, type. And if the interaction led to a sale, the details of the sale were recorded too.

Almost as an aside, the system also gave sales people the opportunity to record their qualitative impressions as free text notes. As you might imagine, this information, though potentially valuable, was never analysed. Sure managers looked at notes in isolation from time to time when referring.to specific customer interactions, but there was no systematic analysis of the corpus as a whole. Nobody had thought it worthwhile to do this, possibly because it is difficult if not quite impossible to analyse unstructured information in the world of relational databases and SQL.

One day, an analyst was browsing data randomly in the system, as good analysts sometimes do. He came across a note that to him seemed like the epitome of a good note…it described what the interaction was about, the customer’s reactions and potential next steps all in a logical fashion.

This gave him an idea. Wouldn’t it be cool, he thought, if we could measure the quality of notes? Not only would this tell us something about the customer and the interaction, it may tell us something about the sales person as well.

The analyst was mega excited…but he realised he’d need help. He was an IT guy and as we all know, business folks in big corporations stopped listening to their IT guys long ago. So our IT guy had his work cut out for him.

After much cogitation, he decided to enlist the help of his friend, a strategic business analyst in the marketing department. This lady, who worked in marketing had the trust of the head of marketing. If she liked the idea, she might be able to help sell it to the head of marketing.

As it turned out, the business analyst loved the idea…more important, since she knew what the sales people do on a day to day basis, she could give the IT guy more ideas on how he could build quantitative measures of the quality of notes. For example, she suggested looking for emotion-laden words or mentions of competitor’s products and so on. The IT guy now had some concrete things to work on. The initial results gave them even more ideas, and soon they had more than enough to make a convincing pitch to the head of marketing.

It would take us too far afield to discuss details of the pitch, but what we will say is this: they avoided technical details, instead focusing on the strategic and innovative aspects of the work.

The marketing head liked the idea…what was there not to like? He agreed to support the effort, and the idea became a project….

…and yes, within months the project resulted in new insights into customer behaviour. But that is another story.

The proof of concept – a business fable

The Head of Data Management was a troubled man. The phrase “Big Data” had cropped up more than a few times in a lunch conversation with Jack, a senior manager from Marketing.

Jack had pointedly asked what the data management team was doing about “Big Data”…or whether they were still stuck in a data time warp. This comment had put the Head of Data Management on the defensive. He’d mumbled something about a proof of concept with vendors specializing in Big Data solutions being on the drawing board.

He spent the afternoon dialing various vendors in his contact list, setting up appointments to talk about what they could offer. His words were music to the vendors’ ears; he had no trouble getting them to bite.

The meetings went well. He was soon able to get a couple of vendors to agree to doing proofs of concept, which amounted to setting up trial versions of their software on the organisation’s servers, thus giving IT staff an opportunity to test-drive and compare the vendors’ offerings.

The software was duly installed and the concept duly proven.

…but the Head of Data Management was still a troubled man.

He had sought an appointment with Jack to inform him about the successful proof of concept. Jack had listened to his spiel, but instead of being impressed had asked a simple question that had the Head of Data Management stumped.

“What has your proof of concept proved?” Jack asked.

“What do…do you mean?” stammered the Head of Data Management.

“I don’t think I can put it any clearer than I already have. What have you proved by doing this so-called proof of concept?”

“Umm… we have proved that the technology works,” came the uncertain reply.

“Surely we know that the technology works,” said Jack, a tad exasperated.

“Ah, but we don’t know that it works for us,” shot back the Head of Data Management.

“Look, I’m just a marketing guy, I know very little about IT,” said Jack, “but I do know a thing or two about product development and marketing. I can say with some confidence that the technology– whatever it is – does what it is supposed to do. You don’t need to run a proof of concept to prove that it works. I’m sure the vendors would have done that before they put their product on the market. So, my question remains: what has your proof of concept proved?”

“Well we’ve proved that it does work for us…:

“Proved it works for what??” asked Jack, exasperation mounting. “Let me put it as clearly as I can – what business problem have you solved that you could not address earlier.”

“Well we’ve taken some of the data from our largest databases – the sales database, from your area of work, and loaded it into the Big Data infrastructure.”

“…and then what?”

“Well that’s about it…for now.”

“So, all you have is another database. You haven’t actually done anything that cannot be done on our existing databases. You haven’t tackled a business problem using your new toy,” said Jack.

“Yes, but this is just the start. We’ll now start doing analytics and all that other stuff we were talking about.”

“I’m sorry to say, this is a classic example of putting the cart before the horse,” said Jack, shaking his head in disbelief.

“How so?” challenged the Head of Data Management.

“Should be obvious but may be it isn’t, so let me spell it out. You’ve jumped to a solution – the technology you’ve installed – without taking the time to define the business problems that the technology should address.”

“…but…but you talked about Big Data when we had lunch the other day.”

“Indeed I did. And what I expected was the start of a dialogue between your people and mine about the kinds of problem we would like to address. We know our problems well, you guys know the technology; but the problems should always drive the solution. What you’ve done now is akin to a solution in search of a problem, a cart before a horse”

“I see,” said the Head of Data Management slowly.

And Jack could only hope that he really did see.

Disclaimer:

This is a work of fiction. It could never happen in real life 😉