Archive for the ‘Communication’ Category

Inexplicit knowledge: what people know, but won’t tell

Introduction

Much of the knowledge that exists in organisations remains unarticulated, in the heads of those who work at the coalface of business activities. Knowledge management professionals know this well, and use the terms explicit and tacit knowledge to distinguish between knowledge that can and can’t be communicated via language. Incidentally, the term tacit knowledge was coined by Michael Polanyi – and it is important to note that he used it in a sense that is very different from what it has come to mean in knowledge management. However, that’s a topic for another post. In the present post I look at a related issue that is common in organisations: the fact that much of what people know can be made explicit, but isn’t. Since the discipline of knowledge management is in dire need of more jargon, I call this inexplicit knowledge. To borrow a phrase from Polanyi, inexplicit knowledge is what people know, but won’t tell. Below, I discuss reasons why potentially explicit knowledge remains inexplicit and what can be done about it.

Why inexplicit knowledge is common

Most people would have encountered work situations in which they chose “not to tell” – remaining silent instead of sharing knowledge that would have been helpful. Common reasons for such behaviour include:

- Fear of loss of ownership of the idea: People are attached to their ideas. One reason for not volunteering their ideas is the worry that someone else in the organisation (a peer or manager) might “steal” the idea. Sometimes such behaviour is institutionalised in the form of an “innovation committee” that solicits ideas, offering monetary incentives for those that are deemed the best (more on incentives below). Like most committee-based solutions, this one is a dud. A better option may be to put in place mechanisms to ensure that those who conceive and volunteer ideas are encouraged to see them through to fruition.

- Fear of loss of face and/or fear of reprisals: In organisational cultures that are competitive, people may fear that their ideas will be ridiculed or put down by others. Closely related to this is the fear of reprisals from management. This happens often enough, particularly when the idea challenges the status quo or those in positions of authority. One of the key responsibilities of management is to foster an environment in which people feel psychologically safe to volunteer ideas, however controversial or threatening the ideas may be.

- Lack of incentives: Some people may be willing to part with their ideas, but only at a price. To address this, organisations may offer extrinsic rewards (i.e. material items such as money, gift vouchers etc) for worthwhile ideas. Interestingly, research has shown that non-monetary extrinsic rewards (meals, gifts etc.) are more effective than monetary ones. This makes sense – financial rewards are more easily forgotten; people are more likely to remember a meal at a top-flight restaurant than a 500$ cheque. That said, it is important to note that extrinsic rewards can also lead to unintended side effects. For example, financial incentives based on quantity of contributions might lead to a glut of low-quality contributions. See the next point for a discussion of another side effect of extrinsic rewards.

- Wrong incentives: As I have discussed at length in my post on motivation in knowledge management projects, people will contribute their hard earned knowledge only if they are truly engaged in their work. Such people are intrinsically motivated (i.e. internally motivated, independent of material rewards); their satisfaction comes from their work (yes, such people do exist!). Consequently they need little or no supervision. Intrinsic rewards are invariably non-material and they cannot be controlled by management. A surprising fact is that, intrinsically motivated people can actually be turned off – even offended – by material rewards.

Psychological safety and incentives are important factors, but there is an even more important issue: the relationships between people who make up the workgroup.

Knowledge sharing and the theory of cooperative action

The work of Elinor Ostrom on collective (or cooperative) action is relevant here because knowledge sharing is a form of cooperation. According to the theory of cooperative action, there are three core relationships that promote cooperation in groups: trust, reciprocity and reputation. Below I take a look at each of these in the context of knowledge sharing:

Trust: In the end, whether we choose to share what we know is largely a matter of trust: if we believe that others will respond positively – be it through acknowledgement or encouragement via tangible or intangible rewards – then the chances are that we will tell what we know. On the other hand, if the response is likely to be negative, we may prefer to remain silent.

Reciprocity: This refers to strategies that are based on treating people in the way we believe they would treat us. We are more likely to share what we know with others if we have reason to believe that they would be just as open with us.

Reputation: This refers to the views we have about the individuals we work with. Although such views may be developed by direct observation of peoples’ behaviours, they are also greatly influenced by opinions of others. The relevance of reputation is that we are more likely to be open with people who have a good reputation.

According to Ostrom, these core relationships can be enhanced by face-to-face communication and organisational rules/ norms that promote openness. See my post on Ostrom’s work and its relevance to project management for more on this.

Summing up

One of the key challenges that organisations face is to get people working together in a cooperative manner. Among other things this includes getting people to share their knowledge; to “tell what they know.” Unfortunately, much of this potentially explicit knowledge remains inexplicit, locked away in peoples’ heads, because there is no incentive to share or, even worse, there are factors that actively discourage people from sharing what they know. These issues can be tackled by offering employees the right incentives and creating the right environment. As important as incentives are, the latter is the more important factor: the key to unlocking inexplicit knowledge lies in creating an environment of trust and openness.

On the meaning and interpretation of project documents

Introduction

Most projects generate reams of paperwork ranging from business cases to lessons learned documents. These are usually written with a specific audience in mind: business cases are intended for executive management whereas lessons learned docs are addressed to future project staff (or the portfolio police…). In view of this, such documents are intended to convey a specific message: a business case aims to convince management that a project has strategic value while a lessons learnt document offers future project teams experience-based advice.

Since the writer of a project document has a clear objective in mind, it is natural to expect that the result would be largely unambiguous. In this post, I look at the potential gap between the meaning of a project document (as intended by the author) and its interpretation (by a reader). As we will see, it is far from clear that the two are the same – in fact, most often, they are not. Note that the points I make apply to any kind of written or spoken communication, not just project documents. However, in keeping with the general theme of this blog, my discussion will focus on the latter.

Meaning and truth

Let’s begin with an example. Consider the following statement taken from this sample business case:

“ABC Company has an opportunity to save 260 hours of office labor annually by automating time-consuming and error-prone manual tasks.”

Let’s ask ourselves: what is the meaning of this sentence?

On the face of it, the meaning of a sentence such as the one above is equivalent to knowing the condition(s) under which the claim it makes is true. For example, the statement above implies that if the company undertakes the project (condition) then it will save the stated hours of labour (claim). This interpretation of meaning is called the truth-conditional model. Among other things, it assumes that the truth of a sentence has an objective meaning.

Most people have something like the truth-conditional model in mind when they are writing documents: they (try to) write in a way that makes the truth of their claims plausible or, better yet, evident.

Buehler’s model of language

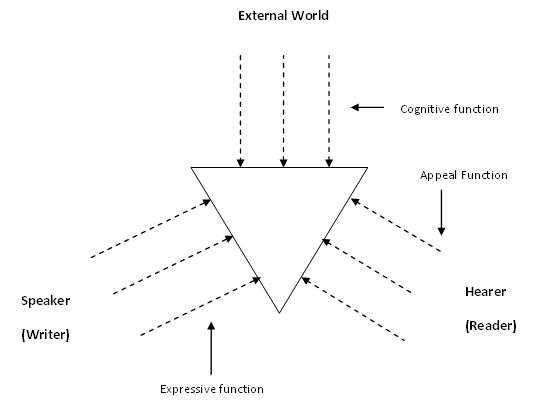

At this point, it is helpful to look at a model of language proposed by the German linguist Karl Buehler in the 1930s. According to Buehler, language has three functions, not just one as in the truth-conditional model. The three functions are:

- Cognitive: representing an (objective) truth about the world. This is the same “truth” as in the truth-conditional model.

- Expressive: expressing a point of view of the writer (or speaker).

- Appeal: making a request of the reader – or “appealing to” the reader.

A graphical representation of the model –sometimes called the organon model – is shown in Figure 1 below.

The basic point Buehler makes is that focusing on the cognitive function alone cannot lead to a complete picture of meaning. One has to factor in the desires and intent of the writer (or speaker) and the predispositions of those who make up the audience. Ultimately, the meaning resides not in some idealized objective truth, but in how readers interpret the document.

Meaning and interpretation

Let’s look at the statement made in the previous section in the light of Buehler’s model.

First, the statement (and indeed the document) makes some claims regarding the external, objective world. This is essentially the same as the truth-conditional view mentioned in the previous section.

Second, from the viewpoint of the expressive function, the statement (and the entire business case, for that matter) selects facts that the writer believes will convince the reader. So, among other things, the writer claims that the company will save 260 hours of manual labour by automating time-consuming and error-prone tasks. The adjectives used imply that some tasks are not carried out efficiently. The author chose to make this point; he or she could have made it another way or even not made it all.

Finally, executives who read the business case might interpret claim made in many different ways depending on:

- Their knowledge of the office environment (things such as the workload of office staff, scope for automation etc.) and the environment. This corresponds to the cognitive function in Buehler’s model.

- Their own predispositions, intentions and desires and those that they impute to the author. This corresponds to the appeal and expressive functions.

For instance, the statement might be viewed as irrelevant by an executive who believes that the existing office staff are perfectly capable of dealing with the workload (“They need to work smarter”, he might say). On the other hand, if he knows that the business case has been written up by the IT department (who are currently looking to justify their budgets), he might well question the validity of the statement and ask for details of how the figure of 260 hours was arrived at. The point is: even a simple and seemingly unambiguous statement (from the point of view of the writer) might be interpreted in a host of unexpected ways.

More than just “sending and receiving”

The standard sender-receiver model of communication is simplistic. Among other things it assumes that interpretation is “just” a matter of interpreting a message correctly. The general assumption is that:

…If the requisite information has been properly packed in a message, only someone who is deficient could fail to get it out. This partitioning of responsibility between the sender and the recipient often results in reciprocal blaming for communication. (Quoted from Questions and Information: contrasting metaphors by Thomas Lauer)

Buehler’s model reminds us that any communication – as clear as it may seem to the sender – is open to being interpreted in a variety of different ways by the receiver. Moreover, the two parties need to understand each others intent and motives, which are generally not open to view.

Wrapping up

The meaning of project documents isn’t as clear-cut as is usually assumed. This is so even for documents that are thought of as being unambiguous (such as contracts or status reports). Writers write from their point of view, which may differ considerably from that of their readers. Further, phrases and sentences which seem clear to a writer can be interpreted in a variety of ways by readers, depending on their situation and motivations. The bottom line is that the writer must not only strive for clarity of expression, but must also try to anticipate ways in which readers might interpret what’s written.

What is the make of that car? A tale about tacit knowledge

My son’s fascination with cars started early: the first word he uttered wasn’t “Mama” or “Dada”, it was “Brrrm.”

His interest grew with him; one of the first games we played together as a family was “What’s the make of that car?” – where his mum or I would challenge him to identify the make of a car that had just overtaken us when we were out driving. The first few times we’d have to tell him what a particular car was (he couldn’t read yet), but soon enough he had a pretty good database in his little head. Exchanges like the following became pretty common:

“So what’s that one Rohan?”

“Mitsubishi Magna, Dad”

“Are you sure?”

“Yes, it is Mitsubishi,” he’d assert, affronted that I would dare question his ability to identify cars.

He was sometimes wrong about the model (and his mum would order me not to make an issue of it). More often than not, though, he’d be right. Neither his mum nor I are car enthusiasts, so we just assumed he figured it out from the logo and / or the letters inscribing the make on the boot.

Then one day we asked him to identify a car that was much too far away for him to be able to see letters or logos. Needless to say, he got it right…

Astounded, I asked, “Did you see the logo when the car passed us?”

“No Dad”

“How did you know then?”

“From the shapes, of course?” As though it were the most obvious thing in the world.

“What shapes?” I was truly flummoxed.

“All cars have different shaped lights and bumpers and stuff.” To his credit, he refrained from saying, didn’t you know that.

“Ah, I see…”

But I didn’t really. Somehow Rohan had intuitively figured out that specific makes and models have unique tail-light, boot and bumper designs. He understood, or knew, car makes and models in a completely different way than we did – his knowledge of cars was qualitatively different from ours.

(I should make it clear that he picked up this particular skill because he enjoys learning about cars; he is, therefore, intrinsically motivated to learn about them. In most other areas his abilities are pretty much in line with kids his age)

—

Of course, the cognoscenti are well aware that cars can be identified by their appearance. I wasn’t, and neither was my dear wife. Those who know cars can identify the make (and even the model) from a mere glance. Moreover, they can’t tell you exactly how they know, they just know – and more often than not they’re right.

This incident came back to me recently, as I was reading Michael Polanyi’s book, The Tacit Dimension, wherein he explains his concept of tacit knowledge (which differs considerably from what it has come to mean in mainstream knowledge management). The basic idea is that we know more than we can tell; that a significant part of our knowledge cannot be conveyed to others via speech or writing. At times we may catch a glimpse of it when the right questions are asked in the right context, but this almost always happens by accident rather than plan. We have to live with the fact that it is impossible for me to understand something you know in the same way that you do. You could explain it to me, I could even practice it under your guidance, but my understanding of it will never be the same as yours.

My point is this: we do not and cannot fully comprehend how others understand and know things, except through fortuitous occurrences. If this is true for a relatively simple matter like car makes and models, what implications does it have for more complex issues that organisations deal with everyday? For example: can we really understand a best practice in the way that folks in the originating organisation do? More generally, are our present methods of capturing and sharing insights (aka Knowledge Management) effective?