Archive for the ‘Decision Making’ Category

Improving decision-making in projects (and life)

Note: This post is based on a presentation that I gave at BA World Sydney on 26th June. It draws from a number of posts that I have written over the last few years.

Introduction – the myth of rational decision making

A central myth about decision making in organisations is that it is a rational process. The qualifier rational refers to decision-making methods that are based on the following broad steps:

- Identify available options.

- Develop criteria for rating options.

- Rate options according to criteria developed.

- Select the top-ranked option.

The truth is that decision making in organisations generally does not follow such a process. As I have pointed out in this post (which is based on this article by Tim van Gelder) decisions are often based on a mix of informal reasoning, personal beliefs and even leaps of faith. . Quoting from that post, formal (or rational) processes often cannot be applied for one or more of the following reasons:

- Real-world options often cannot be quantified or rated in a meaningful way. Many of life’s dilemmas fall into this category. For example, a decision to accept or decline a job offer is rarely made on the basis of material gain alone.

- Even where ratings are possible, they can be highly subjective. For example, when considering a job offer, one candidate may give more importance to financial matters whereas another might consider lifestyle-related matters (flexi-hours, commuting distance etc.) to be paramount. Another complication here is that there may not be enough information to settle the matter conclusively. As an example, investment decisions are often made on the basis of quantitative information that is based on questionable assumptions.

- Finally, the problem may be wicked – i.e. complex, multi-faceted and difficult to analyse using formal decision making methods. Classic examples of wicked problems are climate change (so much so, that some say it is not even a problem) and city / town planning. Such problems cannot be forced into formal decision analysis frameworks in any meaningful way.

The main theme running through all of these is uncertainty. Most of the decisions we are called upon to make in our professional lives are fraught with uncertainty – it is what makes it hard to rate options, adds to the subjectivity of ratings (where they are possible) and magnifies the wickedness of the issue.

Decision making in projects and the need for systematic deliberation

The most important decisions in a project are generally made at the start, at what is sometimes called the “front-end of projects”. Unfortunately this is where information availability is at its lowest and, consequently, uncertainty at its highest. In such situations, decision makers feel that they are left with little choice but to base their decisions on instinct or intuition.

Now, even when one bases a decision on intuition, there is some deliberation involved – one thinks things through and weighs up options in some qualitative way. Unfortunately, in most situations, this is done in an unsystematic manner. Moreover, decision makers fail to record the informal reasoning behind their decisions. As a result the rationale behind decisions made remain opaque to those who want to understand why particular choices were made.

A brief introduction to IBIS

Clearly, what one needs is a means to make the informal reasoning behind a decision explicit. Now there are a number of argument visualisation techniques available for this purpose, but I will focus on one that I have worked with for a while: Issue-Based Information System (IBIS). I will introduce the notation briefly below. Those who want a detailed introduction will find one in my article entitled, The what and whence of issue-based information systems.

IBIS consists of three main elements:

- Issues (or questions): these are issues that need to be addressed.

- Positions (or ideas): these are responses to questions. Typically the set of ideas that respond to an issue represents the spectrum of perspectives on the issue.

- Arguments: these can be Pros (arguments supporting) or Cons (arguments against) an issue. The complete set of arguments that respond to an idea represents the multiplicity of viewpoints on it.

The best IBIS mapping tool is Compendium – it can be downloaded here. In Compendium, the IBIS elements described above are represented as nodes as shown in Figure 1: issues are represented by green question nodes; positions by yellow light bulbs; pros by green + signs and cons by red – signs. Compendium supports a few other node types, but these are not part of the core IBIS notation. Nodes can be linked only in ways specified by the IBIS grammar as I discuss next.

The IBIS grammar can be summarized in a few simple rules:

- Issues can be raised anew or can arise from other issues, positions or arguments. In other words, any IBIS element can be questioned. In Compendium notation: a question node can connect to any other IBIS node.

- Ideas can only respond to questions – i.e. in Compendium “light bulb” nodes can only link to question nodes. The arrow pointing from the idea to the question depicts the “responds to” relationship.

- Arguments can only be associated with ideas – i.e in Compendium + and – nodes can only link to “light bulb” nodes (with arrows pointing to the latter)

The legal links are summarized in Figure 2 below.

The rules are best illustrated by example- follow the links below to see some illustrations of IBIS in action:

- See or this post or this one for examples of IBIS in mapping dialogue.

- See this post or this one for examples of argument visualisation (issue mapping) using IBIS.

The case studies

In my talk, I illustrated the use of IBIS by going through a couple of examples in detail, both of which I have described in detail in other articles. Rather than reproduce them here, I will provide links to the original sources below.

The first example was drawn from a dialogue mapping exercise I did for a data warehousing project. A detailed discussion of the context and process of mapping (along with figures of the map as it developed) are available in a paper entitled, Mapping project dialogues using IBIS – a case study and some reflections (PDF).

The second example, in which I described a light-hearted example of the use of IBIS in a non-work setting, is discussed in my post, What should I do now – a bedtime story about dialogue mapping.

Benefits of IBIS

The case studies serve to highlight how IBIS encourages collective deliberation of issues. Since the issues we struggle with in projects often have elements of wickedness, eliciting opinions from a group through dialogue improves our chances arriving at a “solution” that is acceptable to the group as a whole.

Additional benefits of using IBIS in a group setting include:

- It adds clarity to a discussion

- Serves as a simple and intuitive discussion summary (compare to meeting minutes!)

- Is a common point of reference to move a discussion forward.

- It captures the logic of a decision (decision rationale)

Further still, IBIS disarms disruptive discussion tactics such as “death by repetition” – when a person brings up the same issue over and over again in a million and one different ways. In such situations the mapper simply points to the already captured issue and asks the person if they want to add anything to it. The disruptive behaviour becomes evident to all participants (including the offender).

The beauty of IBIS lies in its simplicity. It is easy to learn – four nodes with a very simple grammar. Moreover, participants don’t need to learn the notation. I have found that most people can understand what’s going on within a few minutes with just a few simple pointers from the mapper.

Another nice feature of IBIS is that it is methodology-neutral. Whatever your methodological persuasion – be it Agile or something that’s BOKsed – you can use it to address decision problems in your project meetings.

Getting started

The best way to learn IBIS is to map out the logic of articles in newspapers, magazines or even professional journals. Once you are familiar with the syntax and grammar, you can graduate to one-on-one conversations, and from there to small meetings. When using it in a meeting for the first time, tell the participants that you are simply taking notes. If things start to work well – i.e. if you are mapping the conversation successfully – the group will start interacting with the map, using it as a basis for their reasoning and as a means to move the dialogue forward. Once you get to this point, you are where you want to be – you are mapping the logic of the conversation.

Of course, there is much more to it than I’ve mentioned above. Check out the references at the end of this piece for more information on mapping dialogues using IBIS.

Wrap up

As this post is essentially covers a talk I gave at a conference, I would like to wrap up with a couple of observations and comments from the audience.

I began my talk with the line, “A central myth about decision making in organisations is that it is a rational process.” I thought many in the audience would disagree. To my surprise, however, there was almost unanimous agreement! The points I made about uncertainty and problem wickedness also seemed to resonate. There were some great examples from the audience on wicked problems in IT – a particularly memorable one about an infrastructure project (which one would normally not think of as particularly wicked) displaying elements of wickedness soon after it was started.

It seems that although mainstream management ignores the sense-making aspect of the profession, many practitioners tacitly understand that making sense out of ambiguous situations is an important part of their work. Moreover, they know that this is best done by harnessing the collective intelligence of a group rather than by enforcing a process or a solution

References:

- Jeff Conklin, Dialogue Mapping: Building Shared Understanding of Wicked Problems, John Wiley, New York (2005). See my review of Conklin’s book here

- Paul Culmsee & Kailash Awati, The Heretic’s Guide to Best Practices: The Reality of Managing Complex Problems in Organisations, iUniverse: Bloomington, Indiana (2011).

The unspoken life of information in organisations

Introduction

Many activities in organisations are driven by information. Chief among these is decision-making : when faced with a decision, those involved will seek information on the available choices and their (expected) consequences. Or so the theory goes.

In reality, information plays a role that does not quite square up with this view. For instance, decision makers may expend considerable time and effort in gathering information, only to ignore it when making their choices. In this case information plays a symbolic role, signifying competence of the decision-maker (the volume of information being a measure of competence) rather than being a means of facilitating a decision. In this post I discuss such common but unspoken uses of information in organisations, drawing on a paper by James March and Martha Feldman entitled Information in Organizations as Symbol and Signal.

Information perversity

As I have discussed in an earlier post, the standard view of decision-making is that choices are based on an analysis of their consequences and (the decision-maker’s) preferences for those consequences. These consequences and preferences generally refer to events in the future and are therefore uncertain. The main role of information is to reduce this uncertainty. In such a rational paradigm, one would expect that information gathering and utilization are consistent with the process of decision making. Among other things this implies that:

- The required information is gathered prior to the decision being made.

- All relevant information is used in the decision-making process.

- All available information is evaluated prior to requesting further information.

- Information that is not relevant to a decision is not collected.

In reality, the above expectations are often violated. For example:

- Information is gathered selectively after a decision has been made (only information that supports the decision is chosen).

- Relevant information is ignored.

- Requests for further information are made before all the information at hand is used.

- Information that has no bearing on the decision is sought.

On the face of it, such behaviour is perverse – why on earth would someone take the trouble to gather information if they are not going to use it? As we’ll see next, there are good reasons for such “information perversity”, some of which are obvious but others that are less so.

Reasons for information perversity

There are a couple of straightforward reasons why a significant portion of the information gathered by organisations is never used. These are:

- Humans have bounded cognitive capacities, so there is a limit to the amount of information they can process. Anything beyond this leads to information overload.

- Information gathered is often unusable in that it is irrelevant to the decision that is to be made.

Although these reasons are valid in many situations, March and Feldman assert that there are other less obvious but possibly more important reasons why information gathered is not used. I describe these in some detail below.

Misaligned incentives

One of the reasons for the mountains of unused information in organisations is that certain groups of people (who may not even be users of information) have incentives to gather information regardless of its utility. March and Feldman describe a couple of scenarios in which this can happen:

- Mismatched interests: In most organisations the people who use information are not the same as those who gather and distribute it. Typically, information users tend to be from business functions (finance, sales, marketing etc.) whereas gatherers/distributors are from IT. Users are after relevant information whereas IT is generally interested in volume rather than relevance. This can result in the collection of data that nobody is going to use.

- “After the fact” assessment of decisions: Decision makers know that many (most?) of their decisions will later turn out to be suboptimal. In other words, after-the-fact assessments of their decision may lead to the realisation that those decisions ought to have been made differently. In view of this, decision makers have good reason to try to anticipate as many different outcomes as they can, which leads to them gathering more information than can be used.

Information as measurement

Often organisations collect information to measure performance or monitor their environments. For example, sales information is collected to check progress against targets and employees are required to log their working times to ensure that they are putting in the hours they are supposed to. Information collected in such a surveillance mode is not relevant to any decision except when corrective action is required. Most of the information collected for this purpose is never used even though it could well contain interesting insights

Information as a means to support hidden agendas

People often use information to build arguments that support their favoured positions. In such cases it is inevitable that information will be misrepresented. Such strategic misrepresentation (aka lying!) can cause more information to be gathered than necessary. As March and Feldman state in the paper:

Strategic misrepresentation also stimulates the oversupply of information. Competition among contending liars turns persuasion into a contest in (mostly unreliable) information. If most received information is confounded by unknown misrepresentations reflecting a complicated game played under conditions of conflicting interests, a decision maker would be curiously unwise to consider information as though it were innocent. The modest analyses of simplified versions of this problem suggest the difficulty of devising incentive schemes that yield unambiguously usable information…

As a consequence, decision makers end up not believing information, especially if it is used or generated by parties that (in the decision-makers’ view) may have hidden agendas.

The above points are true enough. However, March and Feldman suggest that there is a more subtle reason for information perversity in organisations.

The symbolic significance of information

In my earlier post on decision making in organisations I stated that:

…the official line about decision making being a rational process that is concerned with optimizing choices on the basis of consequences and preferences is not the whole story. Our decisions are influenced by a host of other factors, ranging from the rules that govern our work lives to our desires and fears, or even what happened at home yesterday. In short: the choices we make often depend on things we are only dimly aware of.

One of the central myths of modern organisations is that decision making is essentially a rational process. In reality, decision making is often a ritualised activity consisting of going through the motions of identifying choices, their consequences and our preferences for them. In such cases, information has a symbolic significance; it adds to the credibility of the decision. Moreover, the greater the volume of information, the greater the credibility (providing, of course, that the information is presented in an attractive format!). Such a process reaffirms the competence of those involved and reassures those in positions of authority that the right decision has been made, regardless of the validity or relevance of the information used.

Information is thus a symbol of rational decision making; it signals (or denotes) competence in decision making and that the decision made is valid.

Conclusion

In this article I have discussed the unspoken life of information in organisations – how it is used in ways that do not square up to a rational process of decision making. As March and Feldman put it:

Individuals and organizations invest in information and information systems, but their investments do not seem to make decision-theory sense. Organizational participants seem to find value in information that has no great decision relevance. They gather information and do not use it. They ask for reports and do not read them. They act first and receive requested information later.

Some of the reasons for such “information perversity” are straightforward: they include, limited human cognitive ability, irrelevant information, misaligned incentives and even lying! But above all, organisations gather information because it symbolises proper decision making behaviour and provides assurance of the validity of decisions, regardless of whether or not decisions are actually made on a rational basis. To conclude: the official line about information spins a tale about its role in rational decision-making but the unspoken life of information in organisations tells another story.

The shape of things to come: an essay on probability in project estimation

Introduction

Project estimates are generally based on assumptions about future events and their outcomes. As the future is uncertain, the concept of probability is sometimes invoked in the estimation process. There’s enough been written about how probabilities can be used in developing estimates; indeed there are a good number of articles on this blog – see this post or this one, for example. However, most of these writings focus on the practical applications of probability rather than on the concept itself – what it means and how it should be interpreted. In this article I address the latter point in a way that will (hopefully!) be of interest to those working in project management and related areas.

Uncertainty is a shape, not a number

Since the future can unfold in a number of different ways one can describe it only in terms of a range of possible outcomes. A good way to explore the implications of this statement is through a simple estimation-related example:

Assume you’ve been asked to do a particular task relating to your area of expertise. From experience you know that this task usually takes 4 days to complete. If things go right, however, it could take as little as 2 days. On the other hand, if things go wrong it could take as long as 8 days. Therefore, your range of possible finish times (outcomes) is anywhere between 2 to 8 days.

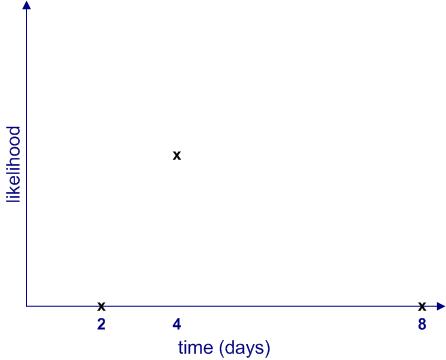

Clearly, each of these outcomes is not equally likely. The most likely outcome is that you will finish the task in 4 days. Moreover, the likelihood of finishing in less than 2 days or more than 8 days is zero. If we plot the likelihood of completion against completion time, it would look something like Figure 1.

Figure 1 begs a couple of questions:

- What are the relative likelihoods of completion for all intermediate times – i.e. those between 2 to 4 days and 4 to 8 days?

- How can one quantify the likelihood of intermediate times? In other words, how can one get a numerical value of the likelihood for all times between 2 to 8 days? Note that we know from the earlier discussion that this must be zero for any time less than 2 or greater than 8 days.

The two questions are actually related: as we shall soon see, once we know the relative likelihood of completion at all times (compared to the maximum), we can work out its numerical value.

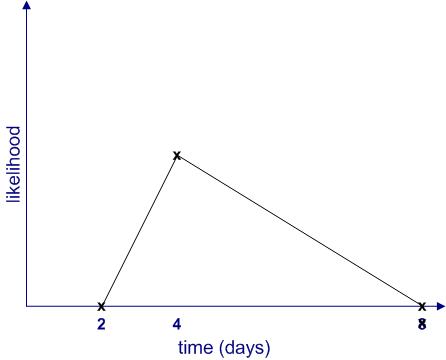

Since we don’t know anything about intermediate times (I’m assuming there is no historical data available, and I’ll have more to say about this later…), the simplest thing to do is to assume that the likelihood increases linearly (as a straight line) from 2 to 4 days and decreases in the same way from 4 to 8 days as shown in Figure 2. This gives us the well-known triangular distribution.

Note: The term distribution is simply a fancy word for a plot of likelihood vs. time.

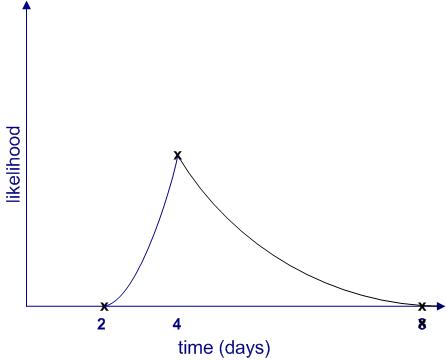

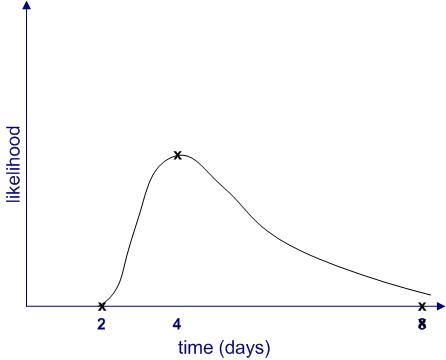

Of course, this isn’t the only possibility; there are an infinite number of others. Figure 3 is another (admittedly weird) example.

Further, it is quite possible that the upper limit (8 days) is not a hard one. It may be that in exceptional cases the task could take much longer (say, if you call in sick for two weeks) or even not be completed at all (say, if you leave for that mythical greener pasture). Catering for the latter possibility, the shape of the likelihood might resemble Figure 4.

From the figures above, we see that uncertainties are shapes rather than single numbers, a notion popularised by Sam Savage in his book, The Flaw of Averages. Moreover, the “shape of things to come” depends on a host of factors, some of which may not even be on the radar when a future event is being estimated.

Making likelihood precise

Thus far, I have used the word “likelihood” without bothering to define it. It’s time to make the notion more precise. I’ll begin by asking the question: what common sense properties do we expect a quantitative measure of likelihood to have?

Consider the following:

- If an event is impossible, its likelihood should be zero.

- The sum of likelihoods of all possible events should equal complete certainty. That is, it should be a constant. As this constant can be anything, let us define it to be 1.

In terms of the example above, if we denote time by and the likelihood by

then:

for

and

And

where

Where denotes the sum of all non-zero likelihoods – i.e. those that lie between 2 and 8 days. In simple terms this is the area enclosed by the likelihood curves and the x axis in figures 2 to 4. (Technical Note: Since

is a continuous variable, this should be denoted by an integral rather than a simple sum, but this is a technicality that need not concern us here)

is , in fact, what mathematicians call probability– which explains why I have used the symbol

rather than

. Now that I’ve explained what it is, I’ll use the word “probability” instead of ” likelihood” in the remainder of this article.

With these assumptions in hand, we can now obtain numerical values for the probability of completion for all times between 2 and 8 days. This can be figured out by noting that the area under the probability curve (the triangle in figure 2 and the weird shape in figure 3) must equal 1. I won’t go into any further details here, but those interested in the maths for the triangular case may want to take a look at this post where the details have been worked out.

The meaning of it all

(Note: parts of this section borrow from my post on the interpretation of probability in project management)

So now we understand how uncertainty is actually a shape corresponding to a range of possible outcomes, each with their own probability of occurrence. Moreover, we also know, in principle, how the probability can be calculated for any valid value of time (between 2 and 8 days). Nevertheless, we are still left with the question as to what a numerical probability really means.

As a concrete case from the example above, what do we mean when we say that there is 100% chance (probability=1) of finishing within 8 days? Some possible interpretations of such a statement include:

- If the task is done many times over, it will always finish within 8 days. This is called the frequency interpretation of probability, and is the one most commonly described in maths and physics textbooks.

- It is believed that the task will definitely finish within 8 days. This is called the belief interpretation. Note that this interpretation hinges on subjective personal beliefs.

- Based on a comparison to similar tasks, the task will finish within 8 days. This is called the support interpretation.

Note that these interpretations are based on a paper by Glen Shafer. Other papers and textbooks frame these differently.

The first thing to note is how different these interpretations are from each other. For example, the first one offers a seemingly objective interpretation whereas the second one is unabashedly subjective.

So, which is the best – or most correct – one?

A person trained in science or mathematics might claim that the frequency interpretation wins hands down because it lays out an objective, well -defined procedure for calculating probability: simply perform the same task many times and note the completion times.

Problem is, in real life situations it is impossible to carry out exactly the same task over and over again. Sure, it may be possible to do almost the same task, but even straightforward tasks such as vacuuming a room or baking a cake can hold hidden surprise (vacuum cleaners do malfunction and a friend may call when one is mixing the batter for a cake). Moreover, tasks that are complex (as is often the case in the project work) tend to be unique and can never be performed in exactly the same way twice. Consequently, the frequency interpretation is great in theory but not much use in practice.

“That’s OK,” another estimator might say,” when drawing up an estimate, I compared it to other similar tasks that I have done before.”

This is essentially the support interpretation (interpretation 3 above). However, although this seems reasonable, there is a problem: tasks that are superficially similar will differ in the details, and these small differences may turn out to be significant when one is actually carrying out the task. One never knows beforehand which variables are important. For example, my ability to finish a particular task within a stated time depends not only on my skill but also on things such as my workload, stress levels and even my state of mind. There are many external factors that one might not even recognize as being significant. This is a manifestation of the reference class problem.

So where does that leave us? Is probability just a matter of subjective belief?

No, not quite: in reality, estimators will use some or all of three interpretations to arrive at “best guess” probabilities. For example, when estimating a project task, a person will likely use one or more of the following pieces of information:

- Experience with similar tasks.

- Subjective belief regarding task complexity and potential problems. Also, their “gut feeling” of how long they think it ought to take. These factors often drive excess time or padding that people work into their estimates.

- Any relevant historical data (if available)

Clearly, depending on the situation at hand, estimators may be forced to rely on one piece of information more than others. However, when called upon to defend their estimates, estimators may use other arguments to justify their conclusions depending on who they are talking to. For example, in discussions involving managers, they may use hard data presented in a way that supports their estimates, whereas when talking to their peers they may emphasise their gut feeling based on differences between the task at hand and similar ones they have done in the past. Such contradictory representations tend to obscure the means by which the estimates were actually made.

Summing up

Estimates are invariably made in the face of uncertainty. One way to get a handle on this is by estimating the probabilities associated with possible outcomes. Probabilities can be reckoned in a number of different ways. Clearly, when using them in estimation, it is crucial to understand how probabilities have been derived and the assumptions underlying these. We have seen three ways in which probabilities are interpreted corresponding to three different ways in which they are arrived at. In reality, estimators may use a mix of the three approaches so it isn’t always clear how the numerical value should be interpreted. Nevertheless, an awareness of what probability is and its different interpretations may help managers ask the right questions to better understand the estimates made by their teams.