Archive for the ‘Decision Making’ Category

Capturing decision rationale on projects

Introduction

Most knowledge management efforts on projects focus on capturing what or how rather than why. That is, they focus on documenting approaches and procedures rather than the reasons behind them. This often leads to a situation where folks working on subsequent projects (or even the same project!) are left wondering why a particular technique or approach was favoured over others. How often have you as a project manager asked yourself questions like the following when browsing through a project archive?

- Why did project decision-makers choose to co-develop the system rather than build it in-house or outsource it?

- Why did the developer responsible for a module use this approach rather than that one?

More often than not, project archives are silent on such matters because the reasoning behind decisions isn’t documented. In this post I discuss how the Issue Based Information System (IBIS) notation can be used to fill this “rationale gap” by capturing the reasoning behind project decisions.

Note: Those unfamiliar with IBIS may want to have a browse of my post on entitled what and whence of issue-based information systems for a quick introduction to the notation and its uses. I also recommend downloading and installing Compendium, a free software tool that can be used to create IBIS maps.

Example 1: Build or outsource?

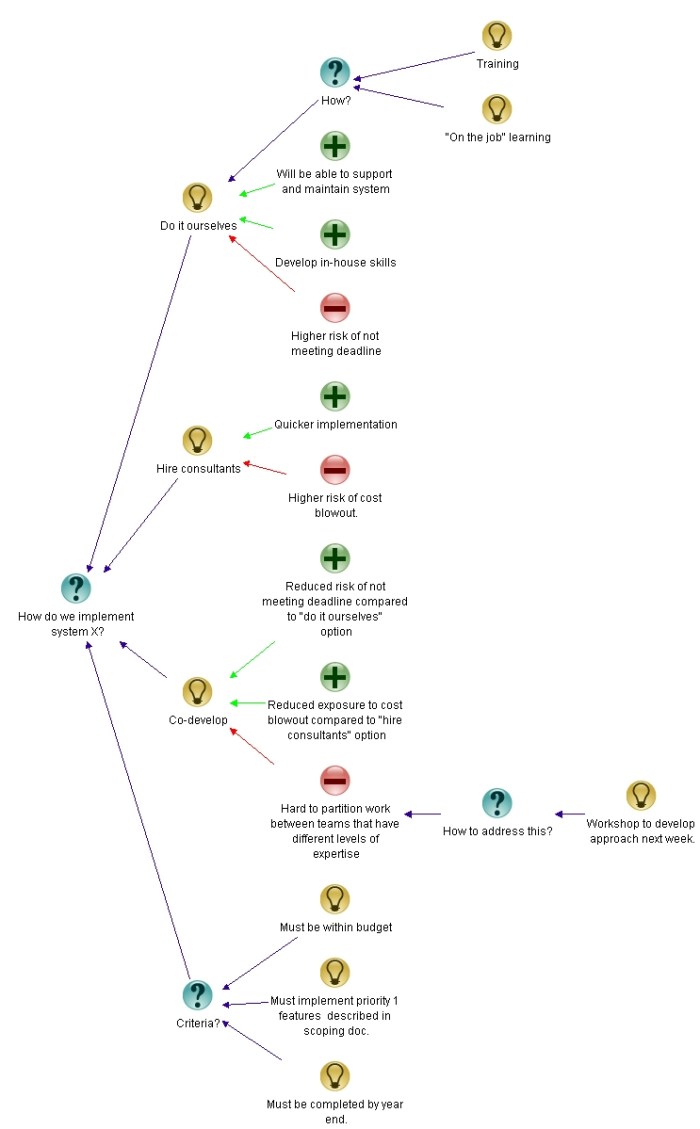

In a post entitled The Approach: A dialogue mapping story, I presented a fictitious account of how a project team member constructed an IBIS map of a project discussion (Note: dialogue mapping refers to the art of mapping conversations as they occur). The issue under discussion was the approach that should be used to build a system.

The options discussed by the team were:

- Build the system in-house.

- Outsource system development.

- Co-develop using a mix of external and internal staff.

Additionally, the selected approach had to satisfy the following criteria:

- Must be within a specified budget.

- Must implement all features that have been marked as top priority.

- Must be completed within a specified time

The post details how the discussion was mapped in real-time. Here I’ll simply show the final map of the discussion (see Figure 1).

Although the option chosen by the group is not marked (they chose to co-develop), the figure describes the pros and cons of each approach (and elaborations of these) in a clear and easy-to-understand manner. In other words, it maps the rationale behind the decision – a person looking at the map can get a sense for why the team chose to co-develop rather than use any of the other approaches.

Example 2: Real-time updates of a data mart

In another post on dialogue mapping I described how IBIS was used to map a technical discussion about the best way to update selected tables in a data mart during business hours. For readers who are unfamiliar with the term: data marts are databases that are (generally) used purely for reporting and analysis. They are typically updated via batch processes that are run outside of normal business hours. The requirement to do real-time updates arose from a business need to see up-to-the-minute reports at specified times during the financial year.

Again, I’ll refer the reader to the post for details, and simply present the final map (see Figure 2).

Since there are a few technical terms involved, here’s a brief rundown of the options, lifted straight from my earlier post (Note: feel free skip this detail – it is incidental to the main point of this post) :

- Use our messaging infrastructure to carry out the update.

- Write database triggers on transaction tables. These triggers would update the data mart tables directly or indirectly.

- Write custom T-SQL procedures (or an SSIS package) to carry out the update (the database is SQL Server 2005).

- Run the relevant (already existing) Extract, Transform, Load (ETL) procedures at more frequent intervals – possibly several times during the day.

In this map the option chosen by the group decision is marked out – it was decided that no additional development was needed; the “real-time” requirement could be satisfied simply by running existing update procedures during business hours (option 4 listed above).

Once again, the reasoning behind the decision is easy to see: the option chosen offered the simplest and quickest way to satisfy the business requirement, even though the update was not really done in real-time.

Summarising

The above examples illustrate how IBIS captures the reasoning behind project decisions. It does so by:

- Making explicit all the options considered.

- Describing the pros and cons of each option (and elaborations thereof).

- Providing a means to explicitly tag an option as a decision.

- Optionally, providing a means to link out to external source (documents, spreadsheets, urls). In the second example I could have added clickable references to documents elaborating on technical detail using the external link capability of Compendium.

Issue maps (as IBIS maps are sometimes called) lay out the reasoning behind decisions in a visual, easy-to-understand way. The visual aspect is important – see this post for more on why visual representations of reasoning are more effective than prose.

I’ve used IBIS to map discussions ranging from project approaches to mathematical model building, and have found them to be invaluable when asked questions about why things were done in a certain way. Just last week, I was able to answer a question about variables used in a market segmentation model that I built almost two years ago – simply by referring back to the issue map of the discussion and the notes I had made in it.

In summary: IBIS provides a means to capture decision rationale in a visual and easy-to-understand way, something that is hard to do using other means.

The Abilene paradox in front-end decision-making on projects

The Abilene paradox refers to a situation in which a group of people make a collective decision that is counter to the preferences or interests of everyone in the group. The paradox was first described by Jerry Harvey, via a story that is summarised nicely in the Wikipedia article on the topic. I reproduce the story verbatim below:

On a hot afternoon in Coleman, Texas, the family is comfortably playing dominoes on a porch, until the father-in-law suggests that they take a trip to Abilene [53 miles north] for dinner. The wife says, “Sounds like a great idea.” The husband, despite having reservations because the drive is long and hot, thinks that his preferences must be out-of-step with the group and says, “Sounds good to me. I just hope your mother wants to go.” The mother-in-law then says, “Of course I want to go. I haven’t been to Abilene in a long time.”

The drive is hot, dusty, and long. When they arrive at the cafeteria, the food is as bad as the drive. They arrive back home four hours later, exhausted.

One of them dishonestly says, “It was a great trip, wasn’t it?” The mother-in-law says that, actually, she would rather have stayed home, but went along since the other three were so enthusiastic. The husband says, “I wasn’t delighted to be doing what we were doing. I only went to satisfy the rest of you.” The wife says, “I just went along to keep you happy. I would have had to be crazy to want to go out in the heat like that.” The father-in-law then says that he only suggested it because he thought the others might be bored.

The group sits back, perplexed that they together decided to take a trip which none of them wanted. They each would have preferred to sit comfortably, but did not admit to it when they still had time to enjoy the afternoon.

Harvey contends that variants of this story play out over and over again in corporate environments. As he states in this paper, organizations frequently take actions in contradiction to what they really want to do and therefore defeat the very purposes they are trying to achieve.

—

The Abilene paradox is essentially a consequence of the failure to achieve a shared understanding of a problem before deciding on a solution. A case in point is Nokia’s ill-judged restructuring circa 2003, initiated in response to the rapidly changing mobile phone market.

Prior to the restructure, Nokia was a product-oriented company that focused on developing one or two new phone models per year. Then, as quoted by an employee in an article published in Helsingin Sanomat (A Finnish daily), Nokia management deemed that: “Two new models a year was no longer enough, but there was a perceived need to bring out as many as 40 or 50 models a year… An utterly terrifying number.” Company management knew that it would be impossible to churn out so many models under the old, product-focused structure. So they decided to reorganise the company into different divisions comprising of teams dedicated to creating standard components (such as cameras), the idea being that standard components could be mixed-and-matched into several “new” phone models every year .

The restructuring and its consequences are described in this article as follows:

[The] re-organisation split Nokia’s all-conquering mobile phones division into three units. The architect was Jorma Ollila, Nokia’s most successful ever CEO, and a popular figure – who steered the company from crisis in 1992 to market leadership in mobile phones – and who as chairman oversaw the ousting of Olli-Pekka Kallasvuo this year [i.e 2010].

In Ollila’s reshuffle, Nokia made a transition from an agile, highly reactive product-focused company to one that managed a matrix, or portfolio. The phone division was split into three: Multimedia, Enterprise and Phones, and the divisions were encouraged to compete for staff and resources. The first Nokia made very few products to a very high standard. But after the reshuffle, which took effect on 1 January 2004, the in-fighting became entrenched, and the company being increasingly bureaucratic. The results were pure Dilbert material.

That the Nokia restructure was possibly a “trip to Abilene” is suggested by the following excerpt from an interview with a long-time Nokia employee (see part IV of the Helsingin Salomat article):

…Even CEO Jorma Ollila was less than enthusiastic about the heavy organisational structure, and recognised perfectly well that it was making Nokia stiff and sluggish in its movements. In their time, Ollila’s views made it all the way down to the factory floor.

But was it not Jorma Ollila himself who created the organisation he led?

“Yes”, replies the woman.Ollila’s unwavering line was to allow his subordinates freedom, to trust them without tight controls. In this way the then leaders of the business units like Mobile Phones and Multimedia could recruit whom they wanted. And in so doing the number of managers at all levels mushroomed to enormous proportions and the product development channels became clogged…

Management actions aimed at shoring up and boosting Nokia’s market share ended up achieving just the opposite, and the irony is that the restructure did not even have the whole-hearted support of management.

—

Like the Nokia restructuring effort, most projects are initiated in response to a perceived problem. Often times, those responsible for giving the project the go-ahead do not have an adequate appreciation of the problem or the proposed solution. As I have stated in an earlier post:

Many high profile projects fail because they succeed. This paradoxical statement is true because many projects are ill-conceived efforts directed at achieving goals that have little value or relevance to their host organisations. Project management focuses on ensuring that the project goals are achieved in an efficient manner. The goals themselves are often “handed down from above”, so the relevance or appropriateness of these is “out of scope” for the discipline of project management. Yet, the prevalence of projects of dubious value suggests that more attention needs to be paid to “front-end” decision making in projects – that is, decision making in the early stages, in which the initiative is just an idea.

Front-end decisions are difficult because they have to be made on the basis of ambiguous or incomplete information. This makes it all the more important that such decisions incorporate the honest views and opinions of all stakeholders in the organisation (or their nominated representatives). The first step in such a process is to ensure that all stakeholders have a common understanding of the goals of the project – i.e. what needs to be done. The next is to reach a shared understanding of how those goals will be achieved. Such stakeholder alignment can be facilitated through communication-centric, collaborative techniques such as dialogue mapping. Genuine dialogue is the only way to prevent pointless peregrinations to places that an organisation can ill-afford to go to.

What should I do now? A bedtime story about dialogue mapping

It was about half past eight in the evening a couple of weeks ago; I was sitting at my computer at home, writing up some notes for a blog post on issue mapping.

“What are you drawing?” asked my eight year old, Rohan. I hadn’t noticed him. He had snuck up behind me quietly, and was watching me draw an IBIS map. (Note: see my post entitled, the what and whence of issue-based information systems for a quick introduction to IBIS)

“Go to bed,” I said, still looking at the screen. It was past his bedtime.

“…but what are you drawing. What are those questions and arrows and stuff?”

A few minutes won’t hurt, I thought. I turned to him and explained the basics of the notation and how it worked.

“But what good is it,” he asked.

“Good question,” I said. “It has many uses, but one of the most important ones is that it can help people make good decisions.”

“Decisions about what?”

“Anything, I said, “for example: you may want to decide what you should do right now. Well, IBIS can help you make that decision.”

“How?”

“I’ll have to show you,” I said, “and I can’t because you have to go to bed now.” What a cop out, I thought to myself, as I said those words.

“Come on, dad – just a few minutes. I really want to know how it can help me make a decision about what I should do now.”

“You should go to bed.”

“How do I know that’s a good decision? Let’s see what IBIS says,” said the boy.

Brilliant! It was checkmate. I relented.

———

“OK, “ I said, opening a new map in Compendium and drawing a question node. “Every IBIS map begins with a question – we call it the root question. Our root question is: What should I do now?”

I typed in the root question and asked him: “So, tell me: what are the different things you could do now.”

He thought for a bit and said, “I could go to sleep but that’s boring.”

“Good. There are actually two things you’ve said there – an idea (go to sleep) and an argument against it (its boring). Let’s put that down in the map. In an IBIS map, an idea is shown as a light-bulb (as in a comic) and an argument against it by a minus sign.”

The map with the root question along with Rohan’s first response and argument is shown in Figure 1.

He looked at the map and said, “There’s another minus I can think of – it is hard to sleep so early.”

I put that point in and said, “I’m sure you could also think of some plus points for sleeping early.”

“Yes,” he said, “I can get up early and do stuff.”

“What stuff?”

“I can play Wii before I go to school.”

“OK let’s put all that into the map,” I said. “See, an argument supporting an idea is shown as a plus sign. Then, I asked you to explain a bit more about why getting up early is a good thing. Your answer goes into the map as another idea. Notice, also, that the map develops from right to left, starting from the root question.”

The map at this point of the discussion is shown in Figure 2.

“What else can you do now?”

“I can talk to you,” said Rohan.

“And what are the plus points of that?” I asked.

“It is interesting to talk to you.” Ah, the boy has the makings of a diplomat…

“The minus points?”

“You are tired and crabby”

OK, may be he isn’t a diplomat…

The map at this point is shown in Figure 3.

“What else can you do,” I asked, as I cleaned up the map a bit.

“I could spend some time with Vikram.” (Vikram is Rohan’s 4 month old brother).

“What are the plus points of doing that?”

“He does funny things and he’s cute.”

“That’s two points, ” I said, adding them to the map. Then I asked, “What kinds of funny things?”

“He gurgles, smiles and blows spit bubbles.”

“Great,” I said, adding those points as elaborations of “does funny things”.

Rohan said, “I forgot. Vik is asleep so I can’t play with him.”

“OK, so that’s a minus point that rules out the choice,” I said, adding it as an argument against the idea. The map at this point is shown in Figure 4.

“Can you think of anything else you can do?” I asked.

He thought for a while and replied, “I could read.”

“OK,” I said. “What are the plus and minus points of that.”

“It’s interesting,” he said, and then in the same breath added, “but I have nothing to new to read.”

I put these points in as arguments for and against reading. The map at this point is shown in Figure 5.

After finishing I asked, “Anything else you want to add.”

“I could just stay up and watch a movie,” he said.

I stopped myself from vetoing that outright. Instead, I put the point in and asked,” Why do you want to stay up and watch a movie?”

“It’s fun,” he said.

“May be so, but a movie would take too long and you have school tomorrow.”

“School’s boring.”

“I’ll note your point,” I said, “but I’m afraid I have to veto that option.”

“I was just trying it out, dad.”

“I know,” I said, as I updated the map (see Figure 6).

“Can you think of anything else you could do?”

“No.”

“OK, let’s look at where we are. Have a look at the map and tell me what you think.”

Rohan looked at the map for a bit and said, “It shows me all my choices and gives me reasons to choose or not to choose them.”

“Does that help you decide what you should do now?”

“Sort of,” he said, “I know I can’t spend time with Vik because he’s asleep. I can’t talk to you because you’re tired and might get crabby. I can’t stay up and watch a movie because you won’t let me.”

“So what can you do?”

“I can read or go to sleep”

“But you have nothing new to read.,” I pointed out.

“Yes, but I think I could find something that I would like to read again…Yes, I know what I will do – I’ll read for a while and then go to sleep.”

“Sounds like a good idea – that way you get to do two of the things on the list.” I said.

“This IBIS stuff is cool. I think I’ll talk about it at my news this Thursday. It is free choice.” (News is a 2-3 minute presentation that all kids in class get to do once a week. Most often the topic is assigned beforehand, but there’s one free-choice session per term where the kids can talk about anything they want to)

“Great idea,” I said, “I’ll help you make some notes and map images tomorrow. Now you’d really better go off to bed before your mum comes in and gets upset at us both.”

”Good night, dad”

“’night, Rohan”