Archive for the ‘Decision Making’ Category

Unforeseen consequences – an unexpected sequel to my previous post

Introduction – a dilemma resolved?

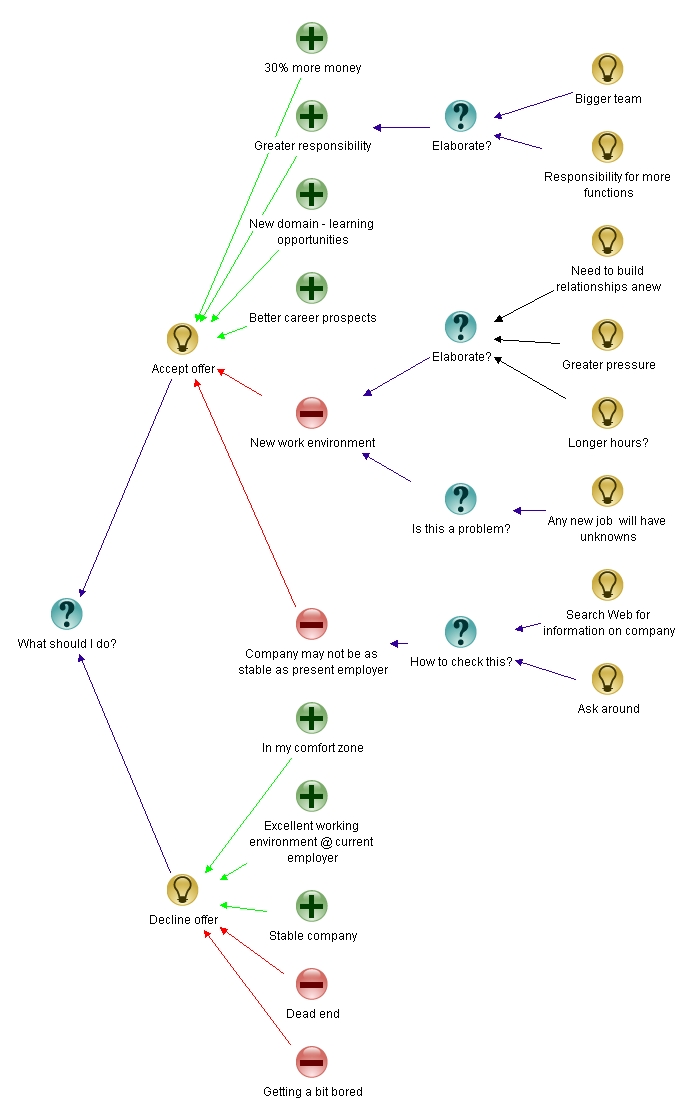

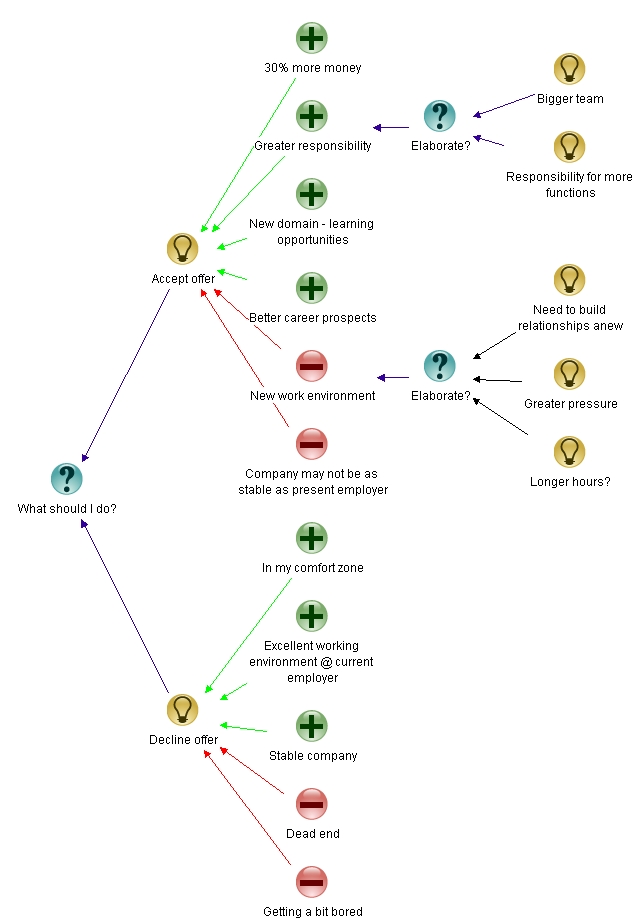

Last week I published a post about how a friend and I used the Issue-based Information System (IBIS) notation to map out a dilemma he was facing – whether to accept or decline a job offer. The final map of that discussion is reproduced in Figure 1 below.

The map illustrates how we analysed the pros and cons of the options before him.

As I’d mentioned in the post, a couple of days after we did the map, he called to tell me that he had accepted the offer. I was pleased that it had worked out for him and was pretty sure that the dilemma was essentially resolved: he’d accepted the job, so that was that.

..or so I thought.

An unforeseen consequence

Last Saturday I happened to meet him again. Naturally, I asked him how things were going – how his current employer had reacted to his resignation etc.

“You’re not going to believe this,” he said. “After he heard that I had resigned, the CEO (who is many levels above me in the org chart) asked to see me immediately.”

“Wow!” I couldn’t help interjecting.

“…Yeah. So, I met him and we had a chat. He told me that management had me marked for a role at a sister organization, at a much higher level than I am at now. So he asked me to hold off for a day or two, until I’d heard what was on offer. When I told him I’d signed the contract already, he said that I should hear what they had to say anyway.”

Wow, indeed – we couldn’t have anticipated this scenario… or could we?

An expert’s observations

In a comment on that post Tim van Gelder makes two important points:

- The options explored in the map (accept/decline) are in fact the same point – one is simply the negation of the other. So this should be represented as a single option (either accept or decline), with the pros arguing for the represented option and the cons arguing for the unrepresented one.

- Options other than the obvious one (accept or decline) should have been explored.

In my response I pointed out that although representing the two options as separate points causes redundancies, it can help participants “see” arguments that may not be obvious immediately. One is drawn to consider each of the actions separately because they are both represented as distinct options, each with their own consequences (I’ll say more about this later in this post). The downside, as Tim mentions, is more clutter and superfluity. This is not necessarily a problem for small maps but can be an issue in larger ones.

However, it is the second point that is more relevant here. In my response to Tim’s comment I stated:

For completeness we ought to have explored options other than the two (one?) that we did, and had we more time we may have done so. That said, my mate viewed this very much as an accept/decline dilemma (precluding other options) because he had only a day to make a decision.

Clearly, in view of what happened, my argument about not having enough time is a complete cop out: we should have made the time to explore the options because it is precisely what had come back to bite us.

Choice and consequence

In hindsight it’s all very well to say that we could have done this or should have done that. The question is: how could we have given ourselves the best possible chance to have foreseen the eventuality that occurred (and others ones that didn’t)?

One way to do this is to explore other ideas in response to the root question: what should I do? (see Figure1). However, it can be difficult for the person(s) facing the dilemma to come up with new ideas when one option looms so much larger than all others. It is the facilitator’s job to help the group come up with options when this happens, and I had clearly failed on this count.

Sure, it can be difficult to come up with options out of the blue – especially when one is not familiar with the context and background of the problem. This highlights the importance of getting a feel for things before the discussion starts. In this case, I should have probed my friends current work situation, how he was regarded at his workplace and his motivations for moving before starting with the map. However, even had I done so, it is moot whether we would have foreseen the particular consequence that occurred.

So, is there any way to get participants thinking about consequences of their choices? Remember, in IBIS one “evaluates” an idea in terms of its pros and cons. Such an analysis may not include consequences .

In my opinion, the best way to get folks thinking about consequences is to ask the question explicitly: “What are the consequences of this idea/option?”

Figure 2 illustrates how this might have worked in the case of my friend’s dilemma. Had we brainstormed the consequences of accepting, he may well have come up with the possibility that actually eventuated.

The branch highlighted in yellow shows how we might have explored the consequences of accepting the job. For each consequence one could then consider how one might respond to it. The exploration of responses could be done on the same map or hived off into its own map as I’ve shown in the figure. Note that clicking on a map node in Compendium (the free software tool used to create IBIS maps) simply opens up a new map. Such sub-maps offer a convenient way to organise complex discussions into relatively self-contained subtopics.

I emphasise that the above is largely a reframing of pros and cons: all the listed consequences can be viewed as pros or cons (depending on whether the consequence is perceived as a negative or a positive one). However asking for consequences explicitly prompts participants to think in terms of what could happen, not just known pros and cons.

Of course, there is no guarantee that this process would have enabled us to foresee the situation that actually occurred. This deceptively simple dilemma is indeed wicked.

Epilogue

On Sunday I happened to re-read Rittel and Webber’s classic paper on wicked problems. In view of what had occurred, it isn’t surprising that the following lines in the paper had a particular resonance:

With wicked problems…. any solution, after being implemented, will generate waves of consequences over an extended–virtually an unbounded– period of time. Moreover, the next day’s consequences of the solution may yield utterly undesirable repercussions which outweigh the intended advantages or the advantages accomplished hitherto. In such cases, one would have been better off if the plan had never been carried out.

The full consequences cannot be appraised until the waves of repercussions have completely run out, and we have no way of tracing all the waves through all the affected lives ahead of time or within a limited time span.

I can’t hope to put it any better than that.

To accept or to decline: mapping life’s little dilemmas using IBIS

Introduction

Last weekend I met up with a friend I hadn’t seen for a while. He looked a bit preoccupied so I asked him what the matter was. It turned out he had been offered a job and was mulling over whether he should accept it or not. This dilemma is fairly representative of some of the tricky personal decisions that we are required to make at various junctures in our lives: there’s never enough information to be absolutely certain about the right course of action, and turning to others for advice isn’t particularly helpful because their priorities and motivations are likely differ from ours.

The question of whether or not to accept a job offer is a wicked problem because it has the following characteristics:

- It is a one-shot operation.

- It is unique.

- One is liable to face the consequences of whatever choice one makes (one has no right to be wrong)

- Since one can make only one choice, one has no opportunity to test the correctness of ones choice.

- The choice one makes (the solution) depends on which aspects of the two choices one focuses on (i.e. the solution depends on ones explanation of the issue).

Admittedly, there are some characteristics of wickedness that the job dilemma does not satisfy. For example, the problem has a definitive formulation (specified by the choices) and there are an enumerable number of choices (accept or decline). Nevertheless, since it satisfies five criteria, one can deem the problem as being wicked. No doubt, those who have grappled with this question in real life will probably agree.

Horst Rittel, the man who coined the term wicked problem also invented the Issue-based Information System (IBIS) notation to document and manage such problems (note that I don’t use the word “solve” because such problems can’t be solved in the conventional sense). The notation is very easy to learn because it has just three elements and a simple grammar – see this post for a quick introduction. Having used IBIS to resolve work related issues before (see this post, for example), I thought it might help my friend if we could used it to visualize his problem and options. So, as we discussed the problem, I did a pencil and paper IBIS map of the issue (I didn’t have my computer handy at the time). In the remainder of this post, I reconstruct the map based on my recollection of the conversation.

Developing the map

All IBIS maps begin with a root question that summarises the issue to be resolved. The dilemma faced by my friend can be summarized by the question:

What should I do (regarding the job offer)?

Questions are represented by blue-green question marks in IBIS (see Figure 1).

There are two possible responses to the question– accept or decline. Responses are referred to as ideas in IBIS, and are denoted by yellow lightbulbs. The root question and the two ideas responding to it are shown in Figure 1.

An IBIS map starts with the root questions and develops towards the right as the discussion progresses.

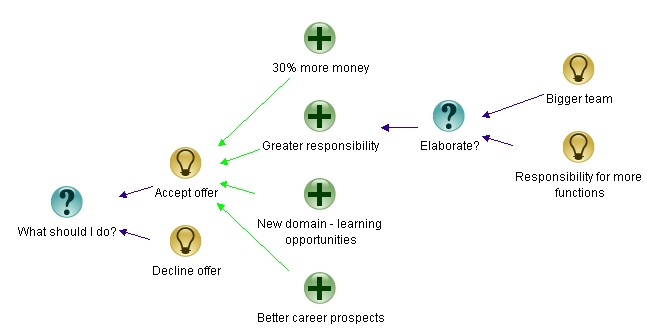

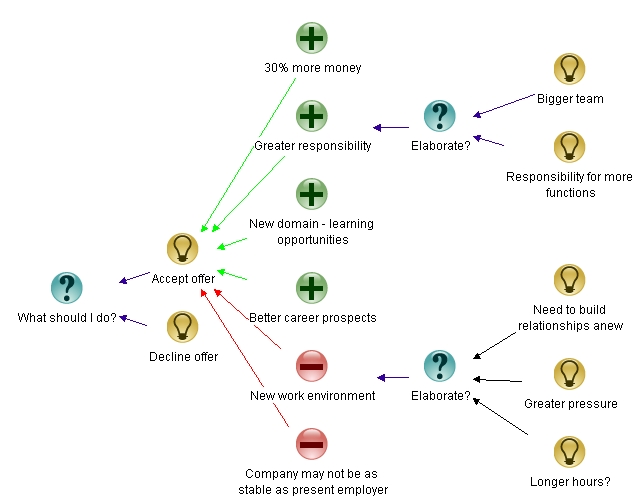

The next step is to formulate arguments for and against each idea. These are referred to as pros and cons in IBIS, and are denoted by a green + and red – sign respectively (See Figures 2 and 3 for examples of these).

We focused on the “accept” option first. The pros were quite easy to see as the offer was generous and the new role a step up from where he was now. I asked him to describe list all the pros he could think of. He mentioned the following:

- Better pay (30% more than current)

- Greater responsibility compared to current job.

- Good learning opportunity (new domain)

- Better career prospects

These points have been depicted in Figure 2.

I felt the second point needed clarification, so I asked him to elaborate on what he meant by “Greater responsibility.” Now, any node in IBIS can be elaborated by asking appropriate questions and responding to them. He mentioned that he would be managing a bigger team which was responsible for a wider range of functions. I broke these up into two points elaborating on the “greater responsibility” point. The elaborations are on the extreme right in Figure 2.

“Do you see any downside to taking the job?” I asked.

“A big one,” he said, “there are all the unknowns that go with a new working environment: the need to build relationships from scratch, greater pressure and possibly longer working hours until I establish my credibility.”

I mapped these points with “New working environment” as the main point and the others as elaborations of it.

I then asked him if there were any other cons he could think of.

“Just one,” he said, “From what I hear, the company may not be as stable as my current employer.”

I added this in and asked him to check if the map was an accurate representation of what he meant. “Yes,” he said, “that’s a good summary of my concerns.”

The map at this stage is shown in Figure 3.

He seemed to be done with the “accept” option, so I suggested moving on to outlining arguments for and against staying with his present employer.

Tellingly, he outlined the pros first:

- He was in his comfort zone – he knew what was expected of him and was able to deliver it with ease.

- The working environment in his company was excellent.

- The company was doing very well and the outlook for the foreseeable future was good.

I mapped these as he spoke. After he was done, I asked him to outline the cons of staying. Almost right away he mentioned the following:

- No prospects for career advancement; the job was a dead end.

- After five odd years, he was getting a bit bored.

The map at this stage is shown in Figure 4.

Through the conversation, he was watching me sketch out the map on paper, but he hadn’t been looking too closely (perhaps because my handwriting is pure chicken scrawl). Nevertheless, at this point he turned the paper around to have a closer look, and said, “Hey, this isn’t bad – my options and reasons for and against them in one glance.”

I asked him if the analysis thus far suggested a choice.

“No,” he said shaking his head.

To make progress, I suggested looking at the cons for both options, to see if these could be mitigated in some way.

We looked at the “stay with the current employer option” – there was really nothing that could be done about the issue of career stagnation or the fact that the work was routine. The company couldn’t create a new position just for him, and the work was all routine because he had done it for so long.

Finally, we turned our attention to the cons of the “move to the new employer” option.

After a while, he said “The uncertainty regarding a new work environment isn’t specific to this employer. It applies to any job – including the ones I may consider in future.”

“That’s an excellent point,” I said, “So we should disregard it, right?”

“Yes. So we’re left with only the stability issue.”

“Perhaps you can search the Web for some information on the company and may be even ask around.”

“I think things are a lot clearer now,” he said as I added the points we’d just discussed to the map.

Figure 5 shows the final result of our deliberations.

Afterword

A few days later he called to tell me that he had accepted the job, but only after satisfying himself that the company was sound. He had to rely on information that he found on the web because no one in his network of accquaintances knew anything about the company. But that’s OK, he said – absolute certainty is impossible when dealing with life’s little dilemmas.

The Approach: a dialogue mapping story

Jack could see that the discussion was going nowhere: the group been talking about the pros and cons of competing approaches for over half an hour, but they kept going around in circles. As he mulled over this, Jack got an idea – he’d been playing around with a visual notation called IBIS (Issue-Based Information System) for a while, and was looking for an opportunity to use it to map out a discussion in real time (Editor’s note: readers unfamiliar with IBIS may want to have a look at this post and this one before proceeding). “Why not give it a try,” he thought, “I can’t do any worse than this lot.” Decision made, he waited for a break in the conversation and dived in when he got one…

“I have a suggestion,” he said. “There’s this conversation mapping tool that I’ve been exploring for a while. I believe it might help us reach a common understanding of the approaches we’ve been discussing. It may even help facilitate a decision. Do you mind if I try it?”

“Pfft – I’m all for it if it helps us get to a decision.” said Max. He’d clearly had enough too.

Jack looked around the table. Mary looked puzzled, but nodded her assent. Rick seemed unenthusiastic, but didn’t voice any objections. Andrew – the boss – had a here-he-goes-again look on his face (Jack had a track record of “ideas”) but, to Jack’s surprise, said, “OK. Why not? Go for it.”

“Give me a minute to get set up,” said Jack. He hooked his computer to the data projector. Within a couple of minutes, he had a blank IBIS map displayed on-screen. This done, he glanced up at the others: they were looking at screen with expressions ranging from curiosity (Mary) to skepticism (Max).

“Just a few words about what I’m going to do, he said. “I’ll be using a notation called IBIS – or issue based information system – to capture our discussion. IBIS has three elements: issues, ideas and arguments. I’ll explain these as we go along. OK – Let’s get started with figuring out what we want out of the discussion. What’s our aim?” he asked.

His starting spiel done, Jack glanced at his colleagues: Max seemed a tad more skeptical than before; Rick ever more bored; Andrew and Mary stared at the screen. No one said anything.

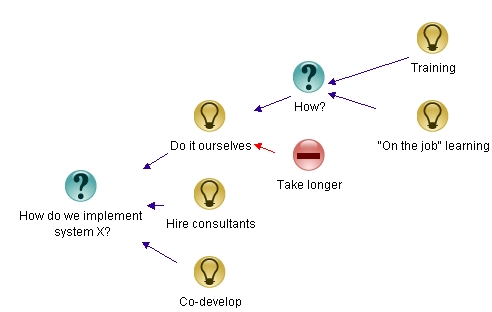

Just as he was about to prompt them by asking another question, Mary said, “I’d say it’s to explore options for implementing the new system and find the most suitable one. Phrased as a question: How do we implement system X?”

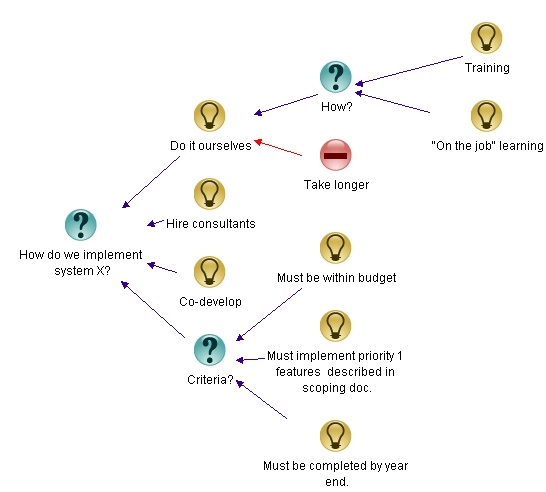

Jack glanced at the others. They all seemed to agree – or at least, didn’t disagree – with Mary, “Excellent,” he said, “I think that’s a very good summary of what we’re trying to do.” He drew a question node on the map and continued: “Most discussions of this kind are aimed at resolving issues or questions. Our root question is: What are our options for implementing system X, or as Mary put it, How do we implement System X.”

“So, what’s next,” asked Max. He still looked skeptical, but Jack could see that he was intrigued. Not bad, he thought to himself….

“Well, the next step is to explore ideas that address or resolve the issue. So, ideas should be responses to the question: how should we implement system X? Any suggestions?”

“We’d have to engage consultants,” said Max. “We don’t have in-house skills to implement it ourselves.”

Jack created an idea node on the map and began typing. “OK – so we hire consultants,” he said. He looked up at the others and continued, “In IBIS, ideas are depicted by light bulbs. Since ideas respond to questions, I draw an arrow from the idea to the root question, like so:

“I think doing it ourselves is an option,” said Mary, “We’d need training and it might take us longer because we’d be learning on the job, but it is a viable option. ”

“Good,” said Jack, “You’ve given us another option and some ways in which we might go about implementing the option. Ideally, each node should represent a single – or atomic – point. So I’ll capture what you’ve said like so.” He typed as fast he could, drawing nodes and filling in detail.

As he wrote he said, “Mary said we could do it ourselves – that’s clearly a new idea – an implementation option. She also partly described how we might go about it: through training to learn the technology and by learning on the job. I’ve added in “How” as a question and the two points that describe how we’d do it as ideas responding to the question.” He paused and looked around to check that every one was with him, then continued. “But there’s more: she also mentioned a shortcoming of doing it ourselves – it will take longer. I capture this as an argument against the idea; a con, depicted as red minus in the map.”

He paused briefly to look at his handiwork on-screen, then asked, “Any questions?”

Rick asked, “Are there any rules governing how nodes are connected?”

“Good question! In a nutshell: ideas respond to questions and arguments respond to ideas. Issues, on the other hand, can be generated from any type of node. I can give you some links to references on the Web if you’re interested.”

“That might be useful for everyone,” said Andrew. “Send it out to all of us.”

“Sure. Let’s move on. So, does anyone have any other options?”

“Umm..not sure how it would work, but what about co-development?” Suggested Rick.

“Do you mean collaborative development with external resources?” asked Jack as he began typing.

“Yes,” confirmed Rick.

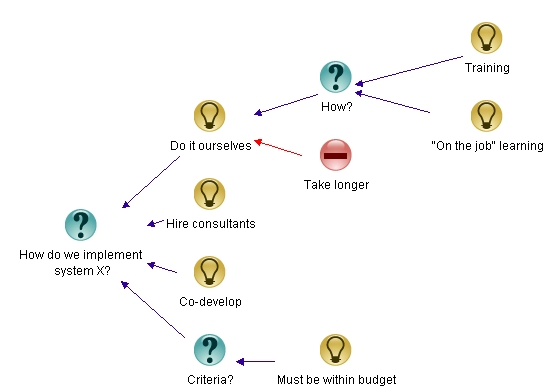

“What about costs? We have a limited budget for this,” said Mary.

“Good point,” said Jack as he started typing. “This is a constraint that must be satisfied by all potential approaches.” He stopped typing and looked up at the others, “This is important: criteria apply to all potential approaches, so the criterial question should hang off the root node,” he said. “Does this make sense to everyone?”

“I’m not sure I understand,” said Andrew. “Why are the criteria separate from the approaches?”

“They aren’t separate. They’re a level higher than any specific approach because they apply to all solutions. Put another way, they relate to the root issue – How do we implement system X – rather than a specific solution.”

“Ah, that makes sense,” said Andrew. “This notation seems pretty powerful.”

“It is, and I’ll be happy to show you some more features later, but let’s continue the discussion for now. Are there any other criteria?”

“Well, we must have all the priority 1 features described in the scoping document implemented by the end of the year,” said Andrew. One can always count on the manager to emphasise constraints.

“OK, that’s two criteria actually: must implement priority 1 features and must implement by year end,” said Jack, as he added in the new nodes. “No surprises here,” he continued, “we have the three classic project constraints – budget, scope and time.”

The others were now engaged with the map, looking at it, making notes etc. Jack wanted to avoid driving the discussion, so instead of suggesting how to move things forward, he asked, “What should we consider next?”

“I can’t think of any other approaches,” said Mary. Does anyone have suggestions, or should we look at the pros and cons of the listed approaches?”

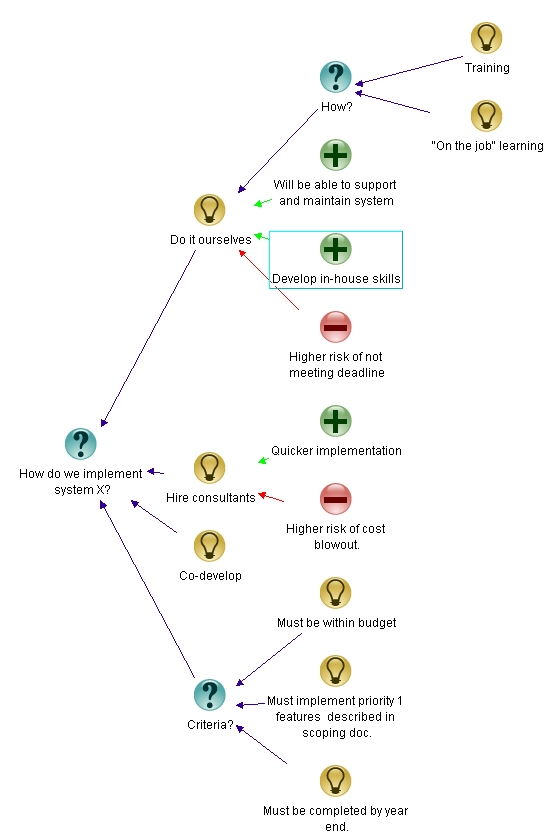

“I’ve said it before; I’ll say it again: I think doing it ourselves is a dum..,.sorry, not a good idea. It is fraught with too much risk…” started Max.

“No it isn’t,” countered Mary, “on the contrary, hiring externals is more risky because costs can blowout by much more than if we did it ourselves.”

“Good points,” said Jack, as he noted Mary’s point. “Max, do you have any specific risks in mind?”

“Time – it can take much longer,” said Max.

“We’ve already captured that as a con of the do-it-ourselves approach,” said Jack.

“Hmm…that’s true, but I would reword it to state that we have a hard deadline. Perhaps we could say – may not finish in allotted time – or something similar.”

“That’s a very good point,” said Jack, as he changed the node to read: higher risk of not meeting deadline. The map was coming along nicely now, and had the full attention of folks in the room.

“Alright,” he continued, “so are there any other cons? If not, what about pros – arguments in support of approaches?”

“That’s easy, “ said Mary, “doing it ourselves will improve our knowledge of the technology; we’ll be able to support and maintain the system ourselves.”

“Doing it through consultants will enable us to complete the project quicker,” countered Max.

Jack added in the pros and paused, giving the group some time to reflect on the map.

Rick and Mary, who were sitting next to each other, had a whispered side-conversation going; Andrew and Max were writing something down. Jack waited.

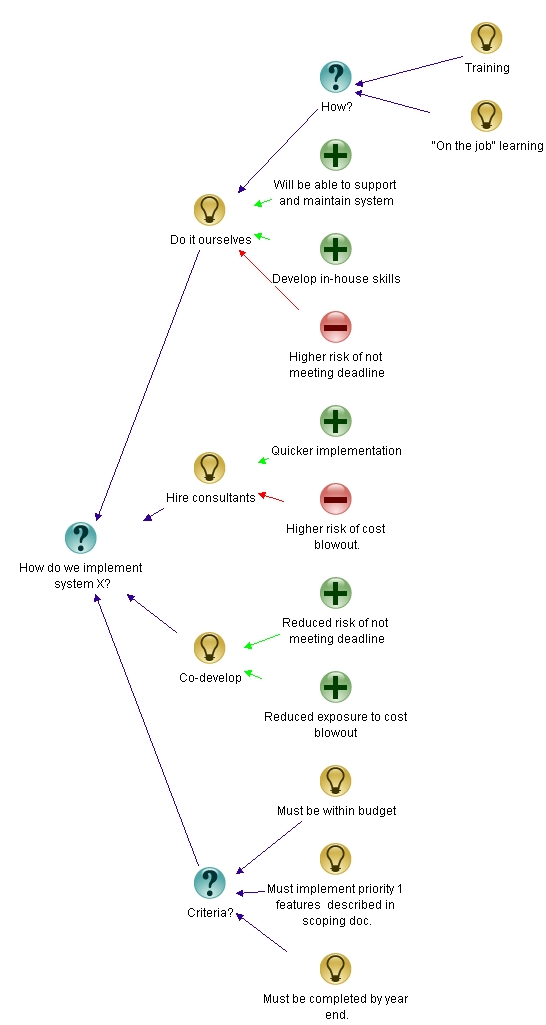

“Mary and I have an idea,” said Rick. “We could take an approach that combines the best of both worlds – external consultants and internal resources. Actually, we’ve already got it down as a separate approach – co-development, but we haven’t discussed it yet..” He had the group’s attention now. “Co-development allows us to use consultants’ expertise where we really need it and develop our own skills too. Yes, we’d need to put some thought into how it would work, but I think we could do it.”

“I can’t see how co-development will reduce the time risk – it will take longer than doing it through consultants.” said Max.

“True,” said Mary, “but it is better than doing it ourselves and, more important, it enables us to develop in-house skills that are needed to support and maintain the application. In the long run, this can add up to a huge saving. Just last week I read that maintenance can be anywhere between 60 to 80 percent of total system costs.”

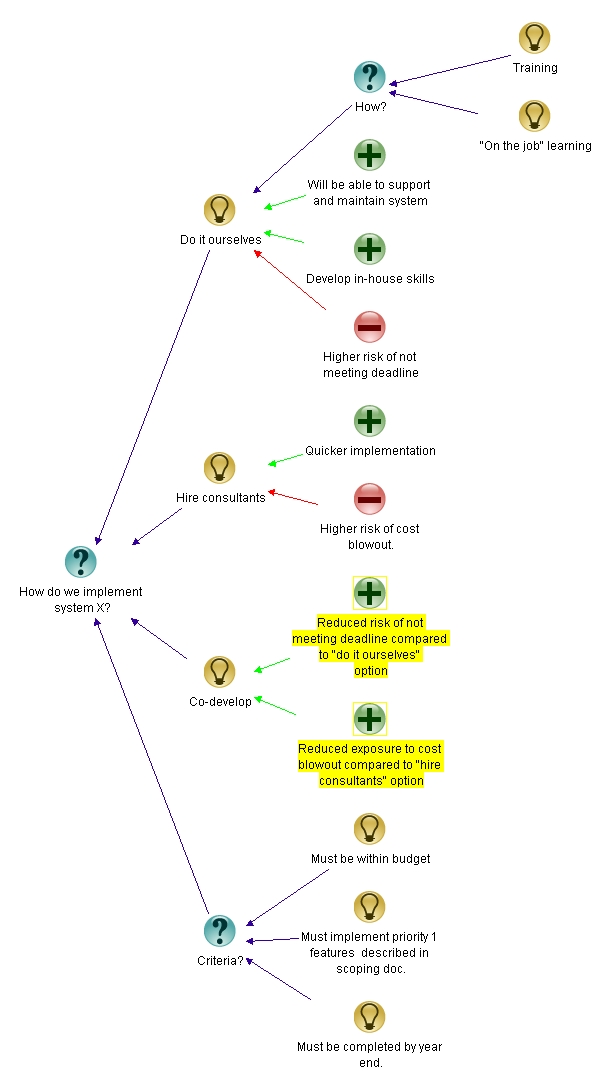

“So you’re saying that it reduces implementation time and results in a smaller exposure to cost blowout?” asked Jack.

“Yes,” said Mary

Jack added in the pros and waited.

“I still don’t see how it reduces time,” said Max.

“It does, when compared to the option of doing it ourselves,” retorted Mary.

“Wait a second guys,” said Jack. “What if I reword the pros to read – Reduced implementation time compared to in-house option and Reduced cost compared to external option.”

He looked at Mary and Max. – both seemed to OK with this, so he typed in the changes.

Jack asked, “So, are there any other issues, ideas or arguments that anyone would like to add?”

“From what’s on the map, it seems that co-development is the best option,” said Andrew. He looked around to see what the others thought: Rick and Mary were nodding; Max still looked doubtful.

Max asked, “how are we going to figure out who does what? It isn’t easy to partition work cleanly when teams have different levels of expertise.”

Jack typed this in as a con.

“Good point,” said Andrew. “There may be ways to address this concern. Do you think it would help if we brought some consultants in on a day-long engagement to workshop a co-development approach with the team? ”

Max nodded, “Yeah, that might work,” he said. “It’s worth a try anyway. I have my reservations, but co-development seems the best of the three approaches.”

“Great,“ said Andrew, “I’ll get some consultants in next week to help us workshop an approach.”

Jack typed in this exchange, as the others started to gather their things. “Anything else to add?” he asked.

Everyone looked up at the map. “No, that’s it, I think,” said Mary.

“Looks good,” said Mike . “Be sure to send us a copy of the map.”

“Sure, I’ll print copies out right away,” said Jack. “Since we’ve developed it together, there shouldn’t be any points of disagreement.”

“That’s true,” said Andrew, “another good reason to use this tool.” Gathering his papers, he asked, “Is there anything else? He looked around the table. “ Alright then, I’ll see you guys later, I’m off to get some lunch before my next meeting.”

Jack looked around the group. Helped along by IBIS and his facilitation, they’d overcome their differences and reached a collective decision. He had thought it wouldn’t work, but it had.

“ Jack, thanks for your help with the discussion. IBIS seems to be a great way to capture discussions. Don’t forget to send us those references,” said Mary, gathering her notes.

“I’ll do that right away,” said Jack, “and I’ll also send you some information about Compendium – the open-source software tool I used to create the map.”

“Great,” said Mary. “I’ve got to run. See you later.”

“See you later,” replied Jack.

————

Further Reading:

1. Jeff Conklin’s book is a must-read for any one interested in dialogue mapping. I’ve reviewed it here.

2. For more on Compendium, see the Compendium Institute site.

3. See Paul Culmsee’s series of articles, The One Best Practice to Rule Them All, for an excellent and very entertaining introduction to issue mapping.

4. See this post and this one for examples of how IBIS can be used to visualise written arguments.

5. See this article for a dialogue mapping story by Jeff Conklin.