Archive for the ‘Decision Making’ Category

Two ways of knowing

I usually don’t pick up calls from unknown numbers but that day, for some reason, I did.

“It’s Raj,” he said, “from your decision-making class.”

As we exchanged pleasantries, I wondered what he was calling about.

“I’m sorry to call out of the blue, but I wanted to tell you about something that happened at work. It relates to what you talked about in last week’s class – using sensemaking techniques to help surface and resolve diverse perspectives on wicked problems.”

[Note: wicked problems are problems that are difficult to solve because stakeholders disagree on what the problem is. A good example of contemporary importance is climate change]

Naturally, I asked Raj to tell me more.

It turned out that he worked for a large IT consulting firm where his main role was to design customised solutions for businesses. The incident he related had occurred at a pre-sales meeting with a potential customer. During the meeting it had become clear that the different stakeholders from the customer side had differing views on what they wanted from the consulting firm.

On the spur of the moment, Raj decided to jump in and help them find common ground.

To do so, he adapted a technique I had discussed at length in class – and I’ll say more about the technique later. It worked a treat – he helped stakeholders resolve their differences and thereby reframe their problem in a more productive way. Ironically, this led to the customer realising that they did not need the solution Raj’s company was selling. However, a senior manager on the customer’s side was so impressed with Raj’s problem framing and facilitation skills that he was keen to continue the dialogue with Raj’s company.

“We think we know our customers through the data we have about them,” said Raj, “but understanding them is something else altogether.”

–x–

In his book, Ways of Attending, Iain McGilchrist draws attention to the asymmetry in the human brain and its consequences for the ways in which we understand the world. His main claim is that the two hemispheres of the brain perceive reality very differently: the left hemisphere sees objects and events through the lens of theories, models and abstractions whereas the right sees them as embedded in and thus related to a larger world. As he puts it:

“The left hemisphere tends to see things more in the abstract, the right hemisphere sees them more embedded in the real-world context in which they occur. As a corollary, the right hemisphere seems better able to appreciate actually existing things in all their uniqueness, while the left hemisphere schematises and generalises things into categories.”

McGilchrist emphasises that both hemispheres are involved in reasoning and emotion, but in very different ways.

“In the left hemisphere, we “experience” our experience in a special way: a “re-presented” version of it, containing now static, separable, bounded, but essentially fragmented entities, grouped into classes on which predictions can be based. This kind of attention isolates, fixes and makes each thing explicit by bringing it under the spotlight of attention. In doing so it renders things inert, mechanical, lifeless. In the other, that of the right hemisphere, we experience the live, complex, embodied world of individual, always unique, beings, forever in flux, a net of interdependencies, forming and reforming wholes, a world with which we are deeply connected.”

It struck me that Raj’s epiphany was deeply connected with McGilchrist’s distinction between the ways in which the two hemispheres of our brains attend to the world.

–x–

The data we collect on our customers (or anything else for that matter) focuses on facts, attributes that are easy to classify or measure. However, such data has its limitations. As McGilchrist notes in his magnum opus, The Master and His Emissary:

“…there is [a] kind of knowledge that comes from putting things together from bits. It is a knowledge of what we call facts. This is not usually well-applied to knowing people. We could have a go – for example, ‘born on 16 September 1964’, ‘lives in New York’, ‘5ft 4inches tall’, ‘red hair’ …, and so on. Immediately you get a sense of somebody who you don’t actually know….What’s more, it sounds as though you’re describing an inanimate object…”

Facts by themselves do not lead to understanding.

–x–

Understanding something requires one to connect the dots between facts, to build a mental model of what is going on. This is a creative act that requires a blend of imaginative and logical thinking.

Since mental models we build are necessarily influenced our beliefs and past experiences, it is unreasonable to expect any two individuals will understand a given situation in exactly the same way. Understanding is a mental process, not a thing, and knowledge (as in knowing something) is an ever-evolving byproduct of the process. Education is not about conveying knowledge, rather it is about helping students expand and refine their individual processes of understanding.

As Heinz von Foerster put it:

“No wonder that an educational system that confuses the process of creating new processes with the dispensing of goods called ‘knowledge’ may cause some disappointment in the hypothetical receivers, for the goods are just not forthcoming: there are no goods.

Historically, I believe, the confusion by which knowledge is taken as substance comes from a witty broadsheet printed in Nuremberg in the Sixteenth Century. It shows a seated student with a hole on top of his head into which a funnel is inserted. Next to him stands the teacher who pours into this funnel a bucket full of “knowledge,” that is, letters of the alphabet, numbers and simple equations.”

The entire business of education is predicated on the assumption that knowledge is transferable and is assimilated by different individuals in exactly the same way. But this cannot be so. As von Foerster so eloquently noted, “the processes [of assimilating knowledge] cannot be passed on… for your nervous activity is just your nervous activity and, alas, not mine”

Since assimilating knowledge (understanding, by another name) is a highly individual activity, it should not be surprising that individuals perceive and understand situations in very different ways. This is precisely the problem that Raj ran into: two stakeholders on the client’s side had different understandings of the problem.

Raj adapted a sensemaking technique called dialogue mapping to help the two stakeholders arrive at a shared understanding of the problem. The technique itself is not as important as the rationale behind it. And that is best conveyed through another story.

—x–

Many years ago, when I worked as a data architect at a large multinational, I was invited to participate in a regional project aimed at building a data warehouse for subsidiaries across Asia. The initiative was driven by the corporate IT office located in Europe. Corporate’s interest in sponsoring this was to harmonize a data landscape that was – to put it mildly – messy. On the other hand, the subsidiaries thought their local systems were just fine. They were suspicious of corporate motives which they saw as a power play that would result in loss of autonomy over data and reporting.

The two parties had diametrically opposite understandings of the problem.

Around that time, I stumbled on the notion of a wicked problem and was researching ways to manage such problems in work contexts. It was clear that the solution lay in getting the two parties on the same page. The question was how.

The trick is to find a way to surface and reconcile diverse viewpoints in a way that takes the heat out of the discussion. One therefore needs a means to make multiple perspectives explicit in a manner that separates opinions from individuals and thus enables a group to develop a shared understanding of contentious issues. There is a visual notation called Issue Based Information System or IBIS that can help facilitators do this. Among other things, IBIS enables one to capture the informal logic of a conversation using a visual notation that has just four node types (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: IBIS node types

In brief: questions (also called issues) capture the problem being discussed; ideas are responses offered to questions; pros and cons are arguments for and against ideas. The claim is that the informal logic of conversations can be captured using just these four node types.

After playing around a bit with the notation, I was convinced it would be of great value in the discussion about the corporate data warehouse. A day prior to the meeting, I met the project lead to canvass the possibility of using IBIS to map the discussion. After seeing a brief demo, he was quite taken by the idea and was happy to have me use it, providing the other participants had no objections.

The discussion took place over the course of a day, with participants drawn from three groups of stakeholders: corporate IT, local IT and business reps from the subsidiaries.

Mapping the conversation using IBIS enabled the group to:

- Agree on the root (key) question – what approach should we take?

- Surface different ideas (options) in response to the question.

- Capture arguments for and against ideas.

As the conversation progressed, I noticed that IBIS took the heat out of the discussion by objectifying discussion points. It did this by separating opinions from their holders. This made it possible for participants to understand (if not quite accept) the rationale behind opposing perspectives. This led them to a more nuanced appreciation of the problem and the proposed solutions.

As the morning wore on, the group gradually converged to a shared understanding of the problem.

By the end of the discussion, it was clear to everyone in the meeting that a subsidiary-focused design that enabled a consistent roll up of data for corporate would be the best option.

Those interested in the details of what I did and how I did it may want to have a look at this paper. However, I should emphasise that the technique is not the point. What happened is that the parties involved changed their minds even though the facts of the matter remained unchanged, and the point is to create the conditions for that to happen.

–x–

The event occurred over a decade ago but has gained significance for me over the years. As we drown in an ever increasing deluge of facts, we are fast losing the capacity to understand. The most pressing problems of today will not be solved by knowing facts, they will be solved by knowing of the other kind.

–x–x–

Boundaries and horizons

James Carse once said, “It is the freedom we all know we have that terrifies us.”

So deep is this terror that we do not want to acknowledge our freedom. As a result, we play within boundaries defined by fear.

–x–

Some time ago, I bumped into a student who had taken a couple of classes that I taught some years ago. Over a coffee, we got talking about his workplace, a large somewhat bureaucratic organisation.

At one point he asked, “We need to change the way we think about and work with data, but I’m not a manager and have no authority to do what needs to be done.”

“Why don’t you demonstrate what you are capable of without waiting for permission?” I replied. “Since you are familiar with your data, it should be easy enough to frame and solve a small problem that makes a difference.”

“My manager will not like that,” he said.

“It is easier to beg forgiveness than seek permission,” I countered.

“He might feel threatened and make life difficult for me.”

“On the other hand, he might appreciate your efforts.”

“You don’t know him,” he replied.

“If you’re not appreciated, you are always free to leave. Moreover, the skills you have learnt in the last two years should give you confidence to exercise that freedom.”

“I’m comfortable where I am,” he said sheepishly, “with my mortgage and all this uncertainty in the economy, I can ill-afford any risk.”

I didn’t say so at the time, but thought it unfortunate that he had set boundaries for himself.

–x–

Boundaries are characteristic of what Carse calls finite games: games that are played with the purpose of winning. These are the games of convention, those that we are familiar with. He contrasts these with infinite games: those whose purpose is the continuation of play.

As a corollary, an infinite game has no winner (or loser) because the game never ends.

Finite games are bounded, both temporally (they last a finite time) and spatially (they are played within a bounded region). As Carse notes in his book, “finite players play within boundaries; infinite players play with boundaries.”

And then a bit later, he tells us how to play with boundaries. “What will undo any boundary is the awareness that it is our vision, and not what we are viewing, that is limited.”

–x–

“I’m resigning,” he said, before launching into an explanation. As he talked, the thing that came to mind was the contrast between his attitude and the student’s.

His explanation was completely unnecessary. I understood.

There comes a tide in the affairs of humans etc…and often that tide is evident only to those who are able and willing to look up and see the possibilities on the distant horizon.

–x–

In contrast to boundaries, horizons are not fixed. As you move towards a horizon it moves away from you. As Carse tells us:

“One never reaches a horizon. It is not a line; it has no place; it encloses no field; its location is always relative to the view. To move toward a horizon is simply to have a new horizon.”

Much of the talk about lifelong learning (which now has its own Wikipedia entry!) is really about taking a horizonal view of life. It has less to do with “staying current” or “learning employable skills” than with gaining new perspectives.

But that does not mean one has to take in the entire vista in one glance. Some new things…no, most new things, take time.

–x–

“I can’t handle failure,” she said. “I’ve always been at the top of my class.”

She was being unduly hard on herself. With little programming experience or background in math, machine learning was always going to be hard going. “Put that aside for now,” I replied. “Just focus on understanding and working your way through it, one step at a time. In four weeks, you’ll see the difference.”

“OK,” she said, “I’ll try.”

She did not sound convinced but to her credit, that’s exactly what she did. Two months later she completed the course with a distinction.

“You did it!” I said when I met her a few weeks after the grades were announced.

“I did,” she grinned. “Do you want to know what the made the difference?”

Yes, I nodded.

“I stopped treating it like a game I had to win,” she said, “and that took the pressure right off. I then started to enjoy learning.”

–x–

For many, success in work…or even in life… is largely a matter of appearances: if one’s career is not marked by a series of increasingly impressive titles then one is likely to be labelled an also-ran, if not an outright failure.

But what is a title? Carse tells us the following:

“What one wins in a finite game is a title. A title is the acknowledgment of others that one has been the winner of a particular game. Titles are public. They are for others to notice. I expect others to address me according to my titles, but I do not address myself with them – unless, of course, I address myself as another. The effectiveness of a title depends on its visibility, its noticeability, to others.”

In these lines, Carse makes some important points. Firstly, a title has to be given to us by others. Secondly, the effectiveness of a title depends on others paying attention to it. That is, its significance lies in the significance that others give it. This is the reason why titles matter to those who compete for them.

–x–

A couple of weeks ago, I invited an ex-student to give a talk to my machine learning class. As I had expected, he did a brilliant job, introducing the class to some tools that they are likely to find useful the future. But the gold lay in something he said in the Q and A session that followed.

“How do you stay up to date in this field?” a student asked.

“Yes, this is a question I struggled with when I started out, ” said Jose. “Data science is a rapidly expanding field and it is impossible to keep pace with it…but let me show you something.” He navigated to his LinkedIn profile and started scrolling through his list of certifications.

It was a long list.

“When I started out,” he continued, “I constantly felt this fear that I was missing out. So, what did I do? I tried to learn everything I could, collecting a bunch of certifications that I kept adding to my profile. One day, I woke up feeling burnt out and asked myself why I was doing this. The only honest answer was because others seemed to think it necessary and even important. That shook me. I started thinking deeply about what I thought was important for myself, what my purpose is. I realised I did not have one; I was running like crazy down a path set by others, not my own. That realisation changed everything for me.”

–x–

Life’s too short to play games and chase titles that others deem important. We are free to play our own game and keep playing it as long as we wish to.

Yes, that can be terrifying.

It can also be liberating.

—-xx—-

Collaborative reasoning in the age of Covid

Ever since the start of the pandemic, there have been no end of opinions, presentations and reports on how we might navigate our way out of the crisis. Much of this takes a narrow, discipline-centric view, which is inadequate because the problem is multifaceted and thus defies traditional disciplinary boundaries. It is therefore of urgent importance to chart a course that considers all aspects of recovery, not just those relevant to specific interests. A recent report produced by the Australian Group of Eight does just that. The key points of the report are concisely described in an executive summary and snapshot, so I will cover just the main points in this article. My focus instead is on the platform used to create the report, as it offers an effective collaborative approach to tackling complex issues in a broad range of contexts.

To me the most amazing thing about the 192-page report is that it was produced by a taskforce comprised of over a hundred academics and researchers across diverse disciplines, collaborating over a three-week period. As stated in the exec summary:

To chart a Roadmap to Recovery we convened a group of over a hundred of the country’s leading epidemiologists, infectious disease consultants, public health specialists, healthcare professionals, mental health and well-being practitioners, indigenous scholars, communications and behaviour change experts, ethicists, philosophers, political scientists, economists and business scholars from the Group of Eight (Go8) universities. The group developed this Roadmap in less than three weeks, through remote meetings and a special collaborative reasoning platform, in the context of a rapidly changing pandemic.

Those who have done any collaborative work involving large groups will have stories to tell about how challenging it is to get a coherent result. This taskforce achieved this in part by working on an online collaborative reasoning platform called SWARM, described in this paper. This post is mainly about what SWARM is and how it works, but I will also describe how the Roadmap taskforce used the platform to come up with a comprehensive recovery plan and the key recommendations made therein. I’ll end with some thoughts on the use of SWARM in broader organizational and business contexts.

The SWARM platform

The platform was designed and implemented by a team led by Drs. Tim van Gelder and Richard de Rozario as part of a large Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA) initiative. In essence, SWARM is a cloud collaboration environment designed to enhance evidence-based reasoning in teams. It does this by supporting an approach called contending analyses, wherein team members produce and refine multiple distinct analyses of a problem, and then select the best one as their collective response.

On SWARM, team members create artefacts that represent their reasoning. Additionally, they can rate, comment on and contribute to artefacts created by others through the course of the challenge. This enables a “best response” to emerge through an iterative process of discussion, refinement and evaluation.

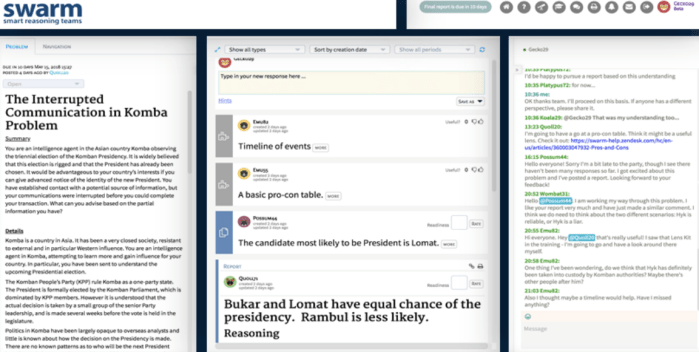

To understand how it works, it is necessary to briefly describe the various ways in which users can interact and contribute to solving the problem with each other in SWARM. The user interface of the SWARM platform consists of three panes (Figure 1).

The left pane contains the problem description and links to related documents. In the centre pane, users can post and update responses. A response may be a Resource (e.g. a link to an external article, a visualisation or an analysis) that contributes to understanding or solving the problem, or it may be a Report, which is a draft candidate for the team’s final output. Users can then comment on and rate others’ responses and comments. The most highly rated Report at the conclusion of the problem is submitted as the result of the group’s collaborative reasoning.

The right pane is a streaming chat window through which users can interact in real-time. To summarise, SWARM users can:

- converse with team members via the chat feed.

- post or update a Resource or a Report

- comment on a Resource or a Report, or

- rate a Resource, Report or Comment.

By design, SWARM does not prescribe (or proscribe) any particular analytical process. As van Gelder, de Rozario and Sinnott (2018, pp. 22-34) note, contending analyses:

…promotes engagement by providing the opportunity for any participant to contribute their own thinking (autonomy), to think in a manner matching their natural expertise (mastery or competence), and to earn the respect of others by drafting a well-regarded response (relatedness)’ – thus meeting each of the three psychological needs identified by self-determination theory.

The idea is that teams should be free to work in ways that suit them collectively, with individuals given the choice to contribute as and when they please. That said, SWARM, via its Lens Kit (https://lenskit.atlassian.net/wiki/spaces/LK/overview), offers participants a compendium of structured analytical techniques and other “logical lenses” that may be useful in analysing complex and uncertain scenarios in which the available information is scarce or ambiguous.

The Roadmap to Recovery project

The Roadmap project involved over a hundred academics from the Group of Eight – a coalition of the oldest, largest and most research-intensive Australian universities. Over three weeks in April 2020, the team worked on developing scenarios for national recovery from the COVID crisis. Their recommendations are available in a comprehensive report. The report is unique in that it synthesises the knowledge of a range of experts and takes a systemic, evidence-based view of the problem. In the words of the co-chairs of the project:

How this document differs from the hundreds of articles and opinion pieces on this issue is that this report specifies the evidence on which it is based, it is produced by researchers who are experts and leaders in their area, and it engages the broadest range of disciplines – from mathematicians, to virologists, to philosophers.

Over a three-week period, this taskforce has debated and discussed, disagreed, and agreed, edited and revised its work over weekdays and holidays, Good Friday and Easter. All remotely. All with social distancing…

…It is research collaboration in action – a collective expression of a belief that expert research can help Government plot the best path forward…

Given the wide geographical distribution of the team and the requirement for social distancing, it was clear that the team needed an online collaboration platform that enabled collective deliberation. Traditional online methods would not have worked for a group this large. As noted in the report:

Standard remote collaboration methods, such as circulating drafts by email, have many drawbacks such as the difficulty of keeping track of document versions, integrating edits and comments on many different versions, and ensuring that everyone can see the latest version. It seemed clear this approach would struggle with an expert group as large as the Roadmap Task Force.

The steering committee therefore decided to give SWARM a go.

As noted in the previous section, SWARM works on the principle that a group should canvas multiple approaches and then collectively settle on the best one, a principle summarised by the term contending analyses. The benefit of such an approach is evident in the report in that it outlines two distinct strategies for recovery:

- Elimination: as the term suggests, this strategy aims at eliminating the virus within the country. This is the lowest risk approach and is technically feasible for a relatively isolated country like Australia. However, the cost in terms of time, effort and money is substantial. Moreover, a strict implementation of this approach would bar international travel for an unrealistically long duration.

- Controlled Adaptation: this involves controlling the infection within the country to a level that does not overwhelm the healthcare system. This is less expensive in terms of time, effort and money, but the outcome is also less certain. However, as the taskforce points out, this could lead to restrictions being eased as early as May 15th, a choice that the government had made before the report was released. This decision is understandable given the cost of extended restrictions; however, it isn’t clear at all how they will handle the inevitable resurgence of the disease down the line. The report considers how things could develop as a result of this decision.

The report aims to provide a balanced case for the two options, and also emphasises that in terms of implementation, the options have considerable overlap. For instance, there are three requirements for the success of either:

- Early detection and supported isolation

- Travel and border restrictions.

- Public trust, transparency and civic engagement.

It should be clear that all three require massive government involvement and support. To this end, the taskforce has formulated an ethical framework that should guide government decision-making and policy. The framework comprises of the following six principles:

- Democratic accountability and the protection of civil liberties.

- Equal access to healthcare and social welfare.

- Shared economic sacrifice.

- Attentiveness to the distinctive patterns of disadvantage.

- Enhancing social well-being and mental health.

- Partnership and shared responsibility

An ethical framework should serve as a check on policy-making that might disadvantage specific groups. If followed, the six principles listed above will ensure that policies are fair to all sections of the community, both in terms of burdens and benefits This is perhaps the trickiest part of policy-making.

Finally, the taskforce has formulated six imperatives (essential rules) that should guide the actual implementation of a recovery. They are:

- The health of our healthcare system and its workers.

- Preparing for relaxation of social distancing.

- Mental health and wellbeing for all.

- The care of indigenous Australians.

- Equity of access and outcomes in health support.

- Clarity of communication.

Each of the above requirements, ethical principles and rules for action are unpacked in detail in the full report and summarised in the executive brief.

How the project unfolded

The Roadmap process was a bold experiment. The Group of Eight had never attempted to pull together such a large report, with so many participants and diverse perspectives, in such a short time, and where no face-to-face meeting was possible. The SWARM platform, still a research prototype, had never previously been used to address a real problem, let alone a problem of this scale and importance.

The project had a steering committee consisting of the project chairs, Professor Shitij Kapur and Go8 CEO Vicki Thomson, and two reasoning experts from the Hunt Lab, Drs. Tim van Gelder and Richard de Rozario. The committee proposed a project design which would involve two weeks working on the SWARM platform, followed by a week of off-platform final report drafting by a small group from the Go8. The two weeks on SWARM would involve the panel of experts working on 9 major topics, corresponding to the anticipated major sections of the final report, such as “How and when to relax social distancing.” It was expected that the experts would distribute themselves across the topics, with “emergent teams” coalescing to work on producing a draft report for each section. Week 1 on SWARM would be mostly “exploratory” thinking, with panelists mostly posting Resources, comments and chat. Week 2 would be mostly “synthetic” thinking, with emergent teams posting early draft Reports for each topic, and collaboratively refining the most promising drafts. In Week 3, these draft section reports would be integrated into a single overall final report.

The steering committee planned to closely monitor progress over the first two weeks and, if/as necessary, modify the process. The project did unfold largely as planned, but the steering committee had to intervene mid-late in the second week when it was apparent that some topics lacked emergent teams with “critical mass,” and in some cases even where critical mass had developed, the teams needed some guidance and prodding to deliver an adequate section report. At this point, the committee, and in particular one of the Chairs, Shitij Kapur, convened a series of zoom meetings meetings the emergent teams, and developed with them a plan for finalising their section reports. From that point on, most work on the draft section reports was done, over just a few days, using more traditional collaboration techniques, such as as circulating a Word document and communicating by email.

Thus, as things turned out, the process was a novel hybrid of a pure SWARM platform-based approach, and more standard methods. The steering committee were committed from the outset to expediency in getting the intended result (a high-quality final report) rather than being “purist” about the approach being used. The use of more traditional collaboration tools and methods later in the process, was driven by a number factors, including some limitations in the SWARM platform (most importantly, the lack of a “track changes” function in the platform’s document editor), and the natural tendency for people to revert to habits and reflexive behaviours when under great pressure. It was clear, however, that the SWARM platform played a crucial role in the first half, allowing participants range across all topics, share lots of ideas and discussion, form emergent teams, and at least start drafting reports.

Whither collaborative reasoning?

The Roadmap project highlights the value of collaborative reasoning platforms like SWARM. It is therefore appropriate to close with a few thoughts on how such platforms can help organisations build internal capability to deal with complex issues that they confront – for example, developing a strategy in an uncertain environment (such as the one we are in currently).

The first point to note is that such problems require stakeholders with diverse viewpoints and skills to work collaboratively to craft a solution. Long-time readers of this blog will know that I advocate tools like Issue-Based Information System (IBIS) to help such groups reach a consensus on problem definition, and thus settle issues around “Are we solving the right problem?” or “How should we approach this issue?” However, once the problem is defined by consensus, the group needs to solve it. This is where platforms like SWARM are particularly useful.

Although SWARM was designed for the intelligence community, the Roadmap project shows that it can be used in other settings. As another example, Tim van Gelder notes that citizen intelligence (where ordinary citizens collaborate on solving intelligence problems) is becoming a thing, but lacks a marketplace. As a possible solution, he envisages the creation of a Kaggle-like platform for complex problems (rather than data problems). He notes that there are challenges around setting up such platforms, but there is interest from large private (non-intelligence) organisations. New deployments of the platform are already underway.

The problems organisations confront in the post-Covid world will be more complex than ever before. There are those who believe such problems will yield to computational approaches that rely primarily on vast quantities of data. However, complex situations cannot be characterised by data alone, so computational approaches will need to be augmented by human sensemaking and reasoning. The success of the Roadmap to Recovery project demonstrates that platforms like SWARM can help organisations tackle such problems by harnessing the power of collaborative reasoning.

Note: For more information on SWARM, please visit the Hunt Lab for Intelligence Research.

Acknowledgement: My thanks to Dr. Tim van Gelder for reviewing a draft version of this article and for contributing the section on how the project unfolded.