Archive for the ‘Emergent Design’ Category

The elusive arch – reflections on navigation and wayfinding

About a decade ago, when GPS technologies were on the cusp of ubiquity, Nicholas Carr made the following observation in a post on his blog:

“Navigation is the most elemental of our skills — “Where am I?” was the first question a creature had to answer — and it’s the one that gives us our tightest connection to the world. The loss of navigational sense is also often the first sign of a mind in decay…If “Where am I?” is the first question a creature had to answer, that suggests something else about us, something very important: memory and navigational sense may, at their source, be one and the same. The first things an animal had to remember were locational: Where’s my home? Where’s that source of food? Where are those predators? So memory may have emerged to aid in navigation.”

The interesting thing, as he notes in the post, is that the connection between memory and navigation has a scientific basis:

“In a 2013 article in Nature Neuroscience, Edvard Moser and his colleague György Buzsáki provided extensive experimental evidence that “the neuronal mechanisms that evolved to define the spatial relationship among landmarks can also serve to embody associations among objects, events and other types of factual information.” Out of such associations we weave the memories of our lives. It may well be that the brain’s navigational sense — its ancient, intricate way of plotting and recording movement through space — is the evolutionary font of all memory.”

If this claim has even a smidgen of truth, it should make you think (very hard!) about the negative effects of following canned directions. Indeed, you’ve probably experienced some of these when your GPS – for whatever reason – decided to malfunction mid-trip.

We find our way through unfamiliar physical or mental terrain by “feeling our way” through it, a process of figuring out a route as one proceeds. This process of wayfinding is how we develop our own, personal mental maps of the unfamiliar.

–x–

A couple of weeks ago, I visited a close friend in Tasmania who I hadn’t met for a while. We are both keen walkers, so he had arranged for us to do the Cape Queen Elizabeth Walk on Bruny Island. The spectacular scenery and cloudy cool weather set the scene for a great day.

From the accounts of others, we knew that the highlight of the walk is the Mars Bluff Arch, a natural formation, carved out of rock over eons by the continual pounding waves. We were keen to get to the arch, but the directions we got from the said accounts were somewhat ambiguous. Witness the following accounts from tripadvisor:

“…it is feasible to reach the Arch even at high tide, but you will get wet. There is only one rock outcropping blocking your way when it’s not low tide (do not try to climb over/on it – it’s too dangerous). Take off your shoes, crop your pants, and walk through the ocean – just beside the visible rocks it’s all sand bottom. I did this at mid-tide and the water came up to my knees at the deepest point. It’s only about a 20 foot long section to walk. Try to time it so you don’t get splashed by waves…”

and

“…We went on low tide so we could walk the beach route as it’s really pretty. The other way around is further on and is about 30 mins longer there is a sign giving you the option once you get close to both directions so don’t worry if you do go on high tide. The Arch was a little hard to find once youre on the beach as it quite the way around through rocks and another cove looks like a solid rock from a distance but once your almost on top of it you see the arch…”

and

“…The tide was against us and so we slogged up the track over Mars Bluff with stunning panoramic views to Cape Elizabeth on one side and out to the Fluted Cape on the other. Had we taken the beach access we would not have enjoyed and marvelled at such stunning views! As we descended to the bleached white sand of the dunes it was interesting to try to determine the type of creatures that had left such an of prints and tracks in the sand. Had we not previously known of the arch’s existence, it would have been hard to find- it’s a real hidden gem, a geometric work of art, tucked away beneath the bluff!”

Daniel had looked up the tide charts, so we knew it was likely we’d have to take the longer route. Nevertheless, when we came to the fork, we thought we’d get down to the beach and check out the low tide route just in case.

As it turned out, the tide was up to the rocks. Taking the beach route would have been foolhardy.

We decided to “slog up the Mars Bluff track”. The thing is, when we got to the cove on the far side, we couldn’t find the damn arch.

–x–

In a walk – especially one that’s done for recreation and fun – exploration is the whole point. Google Map style directions – “walk 2 km due east on the track, turn left at the junction…” would destroy the fun of finding things out for oneself.

In contrast, software users don’t want to spend their time exploring routes through a product, they want the most direct path from where they are to where they want to go. Consequently, good software documentation is unambiguous. It spells out exactly what you need to do to get the product to work the way it should. Technical writers – good ones, at any rate – take great care to ensure that their instructions can be interpreted in only one way.

Surprise is anathema in software, but is welcome in a walk.

–x–

In his celebrated book, James Carse wrote:

“To be prepared against surprise is to be trained. To be prepared for surprise is to be educated.“

Much of what passes for education these days is about avoiding surprise. By Carse’s definition, training to be a lawyer or data scientist is not education at all. Why? I should let Carse speak, for he says it far more eloquently than I ever can:

“Education discovers an increasing richness in the past, because it sees what is unfinished there. Training regards the past as finished and the future as to be finished. Education leads toward a continuing self-discovery; training leads toward a final self-definition. Training repeats a completed past in the future. Education continues an unfinished past into the future.”

Do you want to be defined by a label – lawyer or data scientist – or do you see yourself as continuing an unfinished past into the future?

Do you see yourself as navigating your way up a well-trodden corporate ladder, or wayfinding a route of your own making to a destination unknown?

–x–

What is the difference between navigation and wayfinding?

The former is about answering the question “Where am I?” and “How do I get to where I want to go?”. A navigator seeks an efficient route between two spatial coordinates. The stuff between is of little interest. In contrast, wayfinding is about finding ones way through a physical space. A wayfinder figures out a route in an emergent manner, each step being determined by the nature of the terrain, the path traversed and what lies immediately ahead.

Navigators focus on the destination; to them the journey is of little interest. Wayfinders pay attention to their surroundings; to them the journey is the main point.

The destination is a mirage. Once one arrives, there is always another horizon that beckons.

–x–

We climbed the bluff and took in the spectacular views we would have missed had we taken the beach route.

On descending the other side, we came to a long secluded beach, but there was nary a rock in sight, let alone an arch.

I looked the other way, towards the bluff we had just traversed. Only then did I make the connection – the rocks at the foot of the cliff. It should have been obvious that the arch would likely be adjacent to the cliff But then, nothing was obvious, we had no map on which x marked the spot.

“Let’s head to the cliff,” I said, quickening my pace. I scrambled over rocks at the foot of the cliff and turned my gaze seaward.

There it was, the elusive arch. Not a mark on map, the real thing.

We took the mandatory photographs and selfies, of course. But we also sensed that no camera could capture the magic of the moment. Putting our devices away, we enjoyed a moment of silence, creating our own memories of the arch, the sea, and the horizon beyond.

–x–x–

The ethics and aesthetics of change

I recently attended a conference focused on Agile and systems-based approaches to tackling organizational problems. As one might expect at such a conference, many of the talks were about change – how to approach it, make a case for it, lead it etc. The thing that struck me most when listening to the speakers was how little the discourse on change has changed in the 25 odd years I have been in the business.

This is not the fault of the speakers. They were passionate, articulate and speaking from their own experiences at the coalface of change. Yet there was something missing.

What is lacking is a broad paradigm within which people can make sense of what is going on in their organisations and craft appropriate interventions by and for themselves, instead of imposing “change models” advocated by academics or consultants who have no skin in the game.

–x–

Much of the discourse on organizational change focuses on processes: do this in order to achieve that. To be sure, these approaches also mention the importance of the more intangible personal attitudes such as the awareness and desire for change. However, these too are considered achievable by deliberate actions of those who are “driving” change: do this to create awareness, do that to make people want change and so on.

The approach is entirely instrumental, even when it pretends not to be: people are treated as cogs in a large organizational wheel, to be cajoled, coaxed or coerced to change. This does not work. The inconvenient fact is that you cannot get people to change by telling them to change. Instead, you must reframe the situation in a way that enables them to perceive it in a different light.

They might then choose to change of their own accord.

–x–

Some years ago, I was part of a team that was asked to improve data literacy across an organisation.

Now, what is the first thing that comes to mind when you hear the term “data literacy“?

Chances are you think of it as a skill acquired through training. This is a natural reaction. We are conditioned to think of literacy as skill a acquired through programmed learning which, most often, happens in the context of a class or training program.

In the introduction to his classic Lectures on Physics, Richard Feynman (quoting Edward Gibbons) noted that, “the power of instruction is seldom of much efficacy except in those happy dispositions where it is almost superfluous.” This being so, wouldn’t it be better to use indirect approaches to learning? An example of such an approach is to “sneak” learning opportunities into day-to-day work rather than requiring people to “learn” in the artificial environment of a classroom. This would present employees multiple, even daily, opportunities to learn thus increasing their choices about how and when they learn.

We thought it worth a try.

–x–

It was clear to us that data literacy did not mean the same thing for a frontline employee as it did for a senior manager. Our first action, therefore, was to talk to the people across the organization who we knew worked with data in some way. We asked them questions on what data they used and how they used it. Most importantly we asked them to tell us about the one issue that “kept them up at night” and that they wished they had data about.

Unsurprisingly, the answers differed widely, depending on roles and positions in the organizational hierarchy. Managers wanted reports on performance, year on year trends etc. Frontline staff wanted feedback from customers and suggestions for improvement. There was a wide appreciation of what data could do for them, but an equally wide frustration that the data that was collected through surveys and systems tended to disappear into a data “black hole” never to be seen again or worse, presented in a way that was uninformative.

To tackle the issue, we took the first steps towards making data available to staff in ways that they could use. We did this by integrating customers, sales and demographic data along with survey data that collected feedback from customers and presenting it back to different user groups in ways that they could use immediately (what did customers think of the event? What worked? What didn’t?). We paid particular attention to addressing – if only partially – their responses to the “what keeps you up at night?” question.

A couple of years down the line, we could point to a clear uplift in data usage for decision making across the organization.

–x–

One of the phrases that keeps coming up in change management discussions is the need to “create an environment in which people can change.”

But what exactly does that mean?

How does a middle manager (with a fancy title that overstates the actual authority of the role) create an environment that facilitates change, within a larger system that is hostile to it? Indeed, the biggest obstacles to change are often senior managers who fear loss of control and therefore insist on tightly scripted change management approaches that limit the autonomy of frontline managers to improvise as needed.

Highly paid consultants and high-ranking executives are precisely the wrong people to be micro- scripting changes. If it is the frontline that needs to change, then that is where the story should be scripted.

People’s innate desire for a better working environment presents a fulcrum that is invariably overlooked. This is a shame because it is a point that can be leveraged to great advantage. To find the fulcrum, though, requires change agents to see what is happening on the ground instead of looking for things that confirm preconceived notions of management or fit prescriptions of methodologies.

Once one sees what is going on and acts upon it in a principled way, change comes for free.

–x–

In his wonderful collection of essays on cognition, Heinz von Foerster, articulates two principles that ought to be the bedrock of all change efforts:

The Aesthetical Principle: If you want to see, learn how to act.

The Ethical Principle: Act always to increase choices.

The two are recursively connected as shown in Figure 1: to see, you must act appropriately; if you act appropriately, you will create new choices; the new choices (when enacted) will change the situation, and so you must see again…and so on. Recursively.

This paradigm puts a new spin on the tired old cliche about change being the only constant. Yes, change is unending, the world is Heraclitean, not Parmenidean. Yet, we have more power to shape it than we think, regardless of where we may be in the hierarchy. I first came across these principles over a decade ago and have used them as a guiding light in many of the change initiatives I have been involved in since.

Gregory Bateson once noted that, “what we lack is a theory of action in which the actor is part of the system.” Having used these principles for over a decade, I believe that an approach based on them could be a first step towards such a theory.

–x–

Von Foerster’s ethical and aesthetical imperatives are inspired by the philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein, who made the following statements in his best known book, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus:

- It is clear that ethics cannot be articulated: meaning that ethical behaviour manifests itself through actions not words. Increasing choices for everyone affected by a change is an example of ethical action.

- Ethics and aesthetics are one: meaning that ethical actions have aesthetical outcomes– i.e., outcomes that are beautiful (in the sense of being harmonious with the wider system – an organization in this case)

By their very nature ethical and aesthetical principles do not prescribe specific actions. Instead, they exhort us to truly see what is happening and then devise actions – preferably non-intrusive and oblique – that might enable beneficial outcomes to occur. Doing this requires a sense of place and belonging, one that David Snowden captures beautifully in this essay.

–x–

Perhaps you remain unconvinced by my words. I can understand that. Unfortunately, I cannot offer scientific evidence of the efficacy of this approach; there is no proof and I do not think there will ever be. The approach works by altering conditions, not people, and conditions are hard to pin down. This being so, the effects of the changes are often wrongly attributed causes such as “inspiring leadership” or “highly motivated teams” etc. These are but labels that are used to dodge the question of what makes leadership inspiring or motivating.

A final word.

What is it that makes a work of art captivating? Critics may come up with various explanations, but ultimately its beauty is impossible to describe in words. For much the same reason, art teachers can teach techniques used by great artists, but they cannot teach their students how to create masterpieces.

You cannot paint a masterpiece by numbers but you can work towards creating one, a painting at a time.

The same is true of ethical and aesthetical approaches to change.

–x–x–

Note: The approach described here underpins Emergent Design, an evolutionary approach to sociotechnical change. See this piece for an introduction to Emergent Design and this book for details on how to apply it in the context of building modern data capabilities in organisations (use the code AFL03 for a 20% discount off the list price)

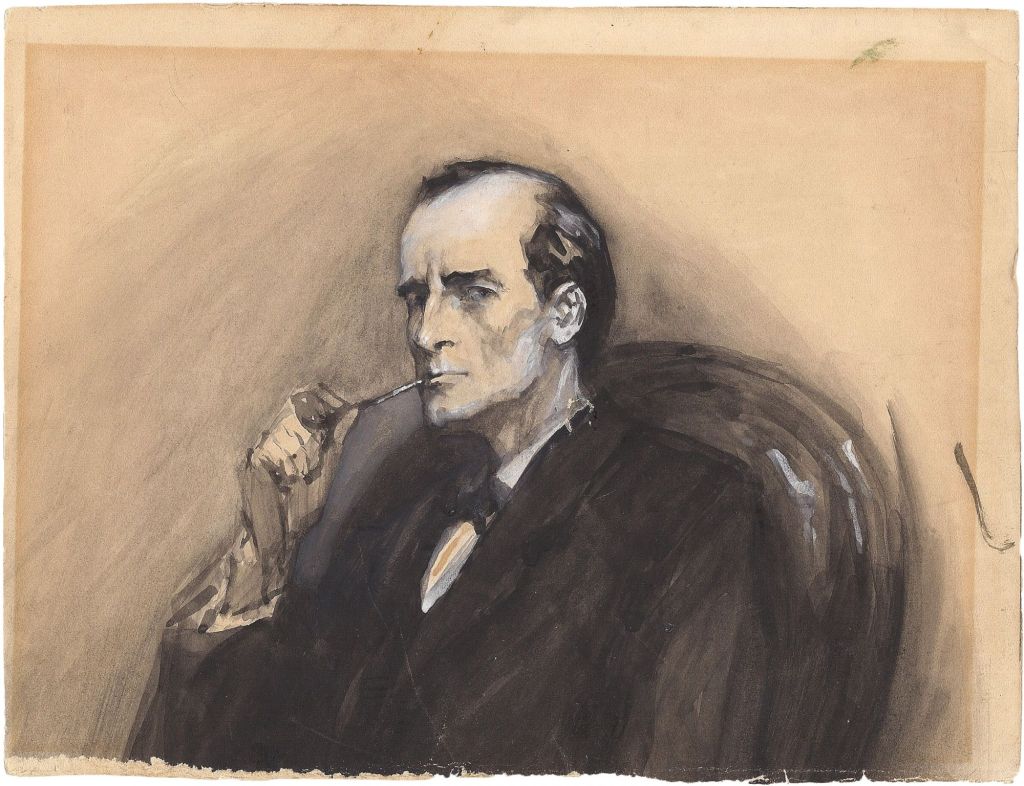

Sherlock Holmes and the case of the Agile rituals

As readers of these chronicles will know, the ebb in demand for the services of private detectives had forced Mr. Holmes to deploy his considerable intellectual powers in the service of large multinationals. Yet, despite many successes, he remained ambivalent about the change.

As he once remarked to me, “the criminal mind is easier to analyse than that of the average executive: the former displays a clarity of thought that tends to be largely absent in the latter.”

Harsh words, perhaps, but judging from the muddle-headed thinking I have witnessed in the corporate world, I think his assessment is fair.

The matter of the Agile rituals is a case in point.

–x–

It was a crisp autumn morning. I had risen at the crack of dawn and gone for my customary constitutional. As I opened the door to 221B on my return, I was greeted by the unmistakable aroma of cooked eggs and bacon. Holmes, who is usually very late in the mornings, save upon those not infrequent occasions when he is up all night, was seated at the table, tucking into an English Breakfast.

“Should you be eating that?” I queried, as I hung my coat on the rack.

“You underestimate the Classic English Breakfast,” he said, waving a fork in my direction. “Yes, its nutritional benefits are overstated, but the true value of the repast lies in the ritual of cooking and consuming it.”

“The ritual?? I was under the impression that rituals have more to do with the church than the kitchen.”

“Ah, Watson, you are mistaken. Practically every aspect of human life has its rituals, whether it be dressing up for work or even doing work. Any activity that follows a set sequence of steps can become a ritual – by which I mean something that can be done without conscious thought.”

“But, is not that an invitation for disaster? If one does not think about what one is doing, one will almost certainly make errors.”

“Precisely,” he replied, “and that is the paradox of ritualisation. There are certain activities that are safe to ritualise, so to speak. Preparing and partaking this spread, for example. It offers the comfort of doing something familiar and enjoyable – and there is no downside, barring a clogged capillary or two. The problem is that there are other activities that, when ritualised, turn out to be downright dangerous.”

“For example?” I was intrigued.

He smiled. “For that I shall ask you to wait until we go to BigCorp’s offices later today.”

“BigCorp??”

“So many questions, Watson. Come with me and all will be clear.”

–x–

We were seated in Jarvis’ office. He was BigCorp’s Head of Technology.

“Mr. Holmes, I was surprised to get your call this morning,” said Jarvis. “You were on site this Monday so I thought it would be at least a few more weeks before we heard from you. Doesn’t it take time to analyse all the information you collected from our teams? From what I was told you took away reams of transcripts and project plans.”

“Not all data is information, most of it is noise,” replied Holmes. “It is of the highest importance, therefore, not to have useless facts elbowing out the useful ones.”

“I see,” said Jarvis. The look on his face said he clearly didn’t.

“Let me get straight to the point,” said Holmes. “BigCorp implemented XXXX Agile framework across the organisation a year ago with the expectation it would improve customer satisfaction with projects delivered. In particular, the intent was to follow Agile Principles. So, you adapted and implemented Agile practices from XXXX that would enable you to operationalise the principles. Would that be a fair summary?” (Editor’s note: the name of the framework has been redacted at Mr. Holmes’ request)

“Yes, that is correct,” nodded Jarvis.

“My conversations with your staff make it clear that the practices and processes have indeed been adapted and implemented. And this has been confirmed by the many project documents I checked,” said Holmes.

“So, where’s the problem then?” queried Jarvis.

“Adopting a practice or process is no guarantee that it will be implemented correctly.” said Holmes.

“I’m not sure I understand.”

“It seems that your staff follow Agile practices ritualistically with no thought about the intent behind them. For example, stand up meetings are treated as forums to enforce specific points of view rather than debate them. Instead of surfacing issues and dealing with them in a way that works for all parties, the meetings invariably end up with winners and losers. This is totally counter to the Agile philosophy. As an observer, it seemed to me that there was no sense of ‘being in it together’ or wanting to get the best outcome for the customer.”

“How many meetings did you attend, Mr. Holmes?””

“Three.”

“Surely that is too small a sample to generalise from,” said Jarvis.

“Not if you know what to look for. You know my method. It is founded upon the observation of trifles. Things such as attitude, tone of voice, engagement, empathy etc. Believe me, I saw enough to tell me what is wrong. Your people have implemented practices but not the intent behind them.”

“I’m not sure I understand.”

“OK, an example might help. One of the Agile principles states that changing requirements are welcomed, even late in development. In one of the meetings I attended, the PM shut down a discussion about changes that the customer wanted by offering technical excuses. The conversation was used to enforce a viewpoint that is centred on BigCorp’s interests rather than those of the customer. Is that not counter to Agile principles? Surely, even if the customer is asking for something unreasonable, it is incumbent on your team to work towards mutual agreement rather than shutting them down summarily.”

“Hmm, I see. So, what do you recommend, Mr. Holmes?”

“You are not going to like what I say, Mr. Jarvis, but the fault lies with you and your management team. You have created an environment that is not conducive to the mindset and dispositions required to be truly Agile. As a result, what you have are its rituals, followed mindlessly. Only you can change that.”

“How?”

“By creating an environment that encourages your staff to develop an Agile mindset without fear of failure. I can recommend a reference or two.”

“That would be helpful Mr. Holmes,” said Jarvis.

Holmes elaborated on the reference and what Jarvis and his team needed to do. The conversation then moved on to other matters that are not relevant to my tale.

–x–

“That was excellent, Holmes,” I remarked, as we made our way out of the BigCorp Office.

“No, it’s elementary,” he replied with a smile, “it is simply that many practitioners prefer not to think about what it means to be Agile. Blindly enacting its rituals is so much easier.”

–x–

Notes:

- There are three quotes taken from Sherlock Holmes stories in the above piece. Can you spot them? (Hint: they are not in the last section.)

- See this post for more on rituals in information system design and development.

- And finally, for a detailed discussion of an approach that privileges intent over process, check out my book on data science strategy.