Archive for the ‘Estimation’ Category

When more knowledge means more uncertainty – a task correlation paradox and its resolution

Introduction

Project tasks can have a variety of dependencies. The most commonly encountered ones are task scheduling dependencies such as finish-to-start and start-to-start relationships which are available in many scheduling tools. However, other kinds of dependencies are possible too. For example, it can happen that the durations of two tasks are correlated in such a way that if one task takes longer or shorter than average, then so does the other. [Note: In statistics such a relationship between two quantities is called a positive correlation and an inverse relationship is termed a negative correlation]. In the absence of detailed knowledge of the relationship, one can model such duration dependencies through statistical correlation coefficients. In my previous post, I showed – via Monte Carlo simulations – that the uncertainty in the duration of a project increases if project task durations are positively correlated (the increase in uncertainty being relative to the uncorrelated case). At first sight this is counter-intuitive, even paradoxical. Knowing that tasks are correlated essentially amounts to more knowledge about the tasks as compared to the uncorrelated case. More knowledge should equate to less uncertainty, so one would expect the uncertainty to decrease compared to the uncorrelated case. This post discusses the paradox and its resolution using the example presented in the previous post.

I’ll begin with a brief recapitulation of the main points of the previous post and then discuss the paradox in some detail.

The example and the paradox

The “project” that I simulated consisted of two identical, triangularly distributed tasks performed sequentially. The triangular distribution for each of the tasks had the following parameters: minimum, most likely and maximum durations of 2, 4 and 8 days respectively. Simulations were carried out for two cases:

- No correlation between the two tasks.

- A correlation coefficient of 0.79 between the two tasks.

The simulations yielded probability distributions for overall completion times for the two cases. I then calculated the standard deviation for both distributions. The standard deviation is a measure of the “spread” or uncertainty represented by a distribution. The standard deviation for the correlated case turned out to be more than 30% larger than that for the uncorrelated case (2.33 and 1.77 days respectively), indicating that the probability distribution for the correlated case has a much wider spread than that for the uncorrelated case. The difference in spread can be seen quite clearly in figure 5 of my previous post, which depicts the frequency histograms for the two simulations (the frequency histograms are essentially proportional to the probability distribution). Note that the averages for the two cases are 9.34 and 9.32 days – statistically identical, as we might expect, because the tasks are identically distributed.

Why is the uncertainty (as measured by the standard deviation of the distribution) greater in the correlated case?

Here’s a brief explanation why. In the uncorrelated case, the outcome of the first task has no bearing on the outcome of the second. So if the first task takes longer than the average time (or more precisely, median time), the second one would have an even chance of finishing before the average time of the distribution. There is, therefore, a good chance in the uncorrelated case that overruns (underruns) in the first task will be cancelled out by underruns (overruns) in the second. This is essentially why the combined distribution for the uncorrelated case is more symmetric than that of the correlated case (see figure 5 of the previous post). In the correlated case, however, if the first task takes longer than the median time, chances are that the second task will take longer than the median too (with a similar argument holding for shorter-than-median times). The second task thus has an effect of amplifying the outcome of the first task. This effect becomes more pronounced as we move towards the extremes of the distribution, thus making extreme outcomes more likely than in the uncorrelated case. This has the effect of broadening the combined probability distribution – and hence the larger standard deviation.

Now, although the above explanation is technically correct, the sense that something’s not quite right remains: how can it be that knowing more about the tasks that make up a project results in increased overall uncertainty?

Resolving the paradox

The key to resolving the paradox lies in looking at the situation after task A has completed but B is yet to start. Let’s look at this in some detail.

Consider the uncorrelated case first. The two tasks are independent, so after A completes, we still know nothing more about the possible duration of B other than that it is triangularly distributed with min, max and most likely times of 2, 4 and 8 days. In the correlated case, however, the duration of B tracks the duration of A – that is, if A takes a long (or short) time then so will B. So, after A has completed, we have a pretty good idea of how long B will take. Our knowledge of the correlation works to reduce the uncertainty in B – but only after A is done.

One can also frame the argument in terms of conditional probability.

In the uncorrelated case, the probability distribution of B – let’s call it p(B) – is independent of A. So the conditional probability of B given that A has already finished (often denoted as P(B|A)) is identical to P(B). That is, there is no change in our knowledge of B after A has completed. Remember that we know p(B) – it is a triangular distribution with min, max and most likely completion times of 2, 4 and 8 days respectively. In the correlated case, however, P(B|A) is not the same as P(B) – the knowledge that A has completed has a huge bearing on the distribution of B. Even if one does not know the conditional distribution of B, one can say with some certainty that outcomes close to the duration of A are very likely, and outcomes substantially different from A are highly unlikely. The degree of “unlikeliness” – and the consequent shape of the distribution – depends on the value of the correlation coefficient.

Endnote

So we see that, on the one hand, positive correlations between tasks increase uncertainty in the overall duration of the two tasks. This happens because a wider range of outcomes are possible when the tasks are correlated. On the other hand knowledge of the correlation can also reduce uncertainty – but only after one of the correlated tasks is done. There is no paradox here, its all a question of where we are on the project timeline.

Of course, one can argue that the paradox is an artefact of the assumption that the two tasks remain triangularly distributed in the correlated case. It is far from obvious that this assumption is correct, and it is hard to validate in the real world. That said, I should add that most commercially available simulation tools treat correlations in much the same way as I have done in my previous post – see this article from the @Risk knowledge base, for example.

In the end, though, even if the paradox is only an artefact of modelling and has no real world application, it is still a good pedagogic example of how probability distributions can combine to give counter-intuitive results.

Acknowledgement:

Thanks to Vlado Bokan for several interesting conversations relating to this paradox.

The effect of task duration correlations on project schedules – a study using Monte Carlo simulation

Introduction

Some time ago, I wrote a couple of posts on Monte Carlo simulation of project tasks: the the first post presented a fairly detailed introduction to the technique and the second illustrated its use via three simple examples. The examples in the latter demonstrated the effect of various dependencies on overall completion times. The dependencies discussed were: two tasks in series (finish-to-start dependency), two tasks in series with a time delay (finish-to-start dependency with a lag) and two tasks in parallel (start-to-start dependency). All of these are dependencies in timing: i.e. they dictate when a successor task can start in relation to its predecessor. However, there are several practical situations in which task durations are correlated – that is, the duration of one task depends on the duration of another. As an example, a project manager working for an enterprise software company might notice that the longer it takes to elicit requirements the longer it takes to customise the software. When tasks are correlated thus, it is of interest to find out the effect of the correlation on the overall (project) completion time. In this post I explore the effect of correlations on project schedules via Monte Carlo simulation of a simple “project” consisting of two tasks in series.

A bit about what’s coming before we dive into it. I begin with a brief discusssion on how correlations are quantified. I then describe the simulation procedure, following which I present results for the example mentioned earlier, with and without correlations. I then present a detailed comparison of the results for the uncorrelated and correlated cases. It turns out that correlations increase uncertainty. This seemed counter-intuitive to me at first, but the simulations helped me see why it is so.

Note that I’ve attempted to keep the discussion intuitive and (largely) non-mathematical by relying on graphs and tables rather than formulae. There are a few formulae but most of these can be skipped quite safely.

Correlated project tasks

Imagine that there are two project tasks, A and B, which need to be performed sequentially. To keep things simple, I’ll assume that the durations of A and B are described by a triangular distribution with minimum, most likely and maximum completion times of 2, 4 and 8 days respectively (see my introductory Monte Carlo article for a detailed discussion of this distribution – note that I used hours as the unit of time in that post). In the absence of any other information, it is reasonable to assume that the durations of A and B are independent or uncorrelated – i.e. the time it takes to complete task A does not have any effect on the duration of task B. This assumption can be tested if we have historical data. So let’s assume we have the following historical data gathered from 10 projects:

| Duration A (days)) | duration B (days) |

| 2.5 | 3 |

| 3 | 3 |

| 7 | 7.5 |

| 6 | 4.5 |

| 5.5 | 3.5 |

| 4.5 | 4.5 |

| 5 | 5.5 |

| 4 | 4.5 |

| 6 | 5 |

| 3 | 3.5 |

Figure 1 shows a plot of the duration of A vs. the duration of B. The plot suggests that there is a relationship between the two tasks – the longer A takes, the chances are that B will take longer too.

In technical terms we would say that A and B are positively correlated (if one decreased as the other increased, the correlation would be negative).

There are several measures of correlation, the most common one being Pearson’s coefficient of correlation which is given by

In this case and

are the durations of the tasks A and B the

th time the project was performed,

the average duration of A,

the average duration of B and

the total number of data points (10 in this case). The capital sigma (

) simply denotes a sum from 1 to N.

The Pearson coefficient, can vary between -1 and 1: the former being a perfect negative correlation and the latter a perfect positive one [Note: The Pearson coefficient is sometimes referred to as the product-moment correlation coefficient]. On calculating for the above data, using the CORREL function in Excel, I get a value of 0.787 (Note that one could just as well use the PEARSON function). This is a good indication that there is something going on here – the two tasks are likely not independent as originally assumed. Note that the correlation coefficient does not tell us anything about the form of the dependence between A and B; it only tells us that they are dependent and whether the dependence is positive or negative. It is also important to note that there is a difference between quantifying the correlation via the Pearson (or any other) coefficient and developing an understanding of why there is a correlation. The coefficient tells us nothing about the latter.

If A and B are correlated as discussed above, simulations which assume the tasks to be independent will not be correct. In the remainder of this article I’ll discuss how correlations affect overall task durations via a Monte Carlo simulation of the aforementioned example.

Simulating correlated project tasks

There are two considerations when simulating correlated tasks. The first is to characterize the correlation accurately. For the purposes of the present discussion I’ll assume that the correlation is described adequately by a single coefficient as discussed in the previous section. The second issue is to generate correlated completion times that satisfy the individual task duration distributions (Remember that the two tasks A and B have completion times that are described by a triangular distribution with minimum, maximum and most likely times of 2, 4 and 8 days). What we are asking for, in effect, is a way to generate a series of two correlated random numbers, each of which satisfy the triangular distribution.

The best known algorithm to generate correlated sets of random numbers in a way that preserves the individual (input) distributions is due to Iman and Conover. The beauty of the Iman-Conover algorithm is that it takes the uncorrelated data for tasks A and B (simulated separately) as input and induces the desired correlation by simply re-ordering the uncorrelated data. Since the original data is not changed, the distributions for A and B are preserved. Although the idea behind the method is simple, it is technically quite complex. The details of the technique aren’t important – but I offer a partial “hand-waving” explanation in the appendix at the end of this post. Fortunately I didn’t have to implement the Iman-Conover algorithm because someone else has done the hard work: Steve Roxburgh has written a graphical tool to generate sets of correlated random variables using the technique (follow this link to download the software and this one to view a brief tutorial) . I used Roxburgh’s utility to generate sets of random variables for my simulations.

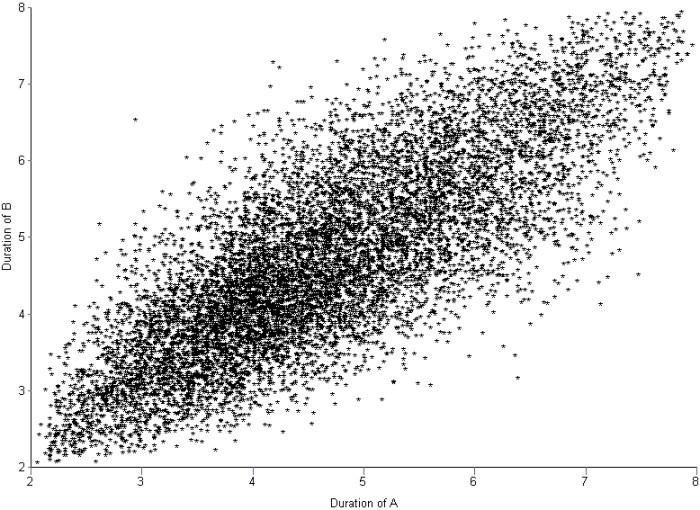

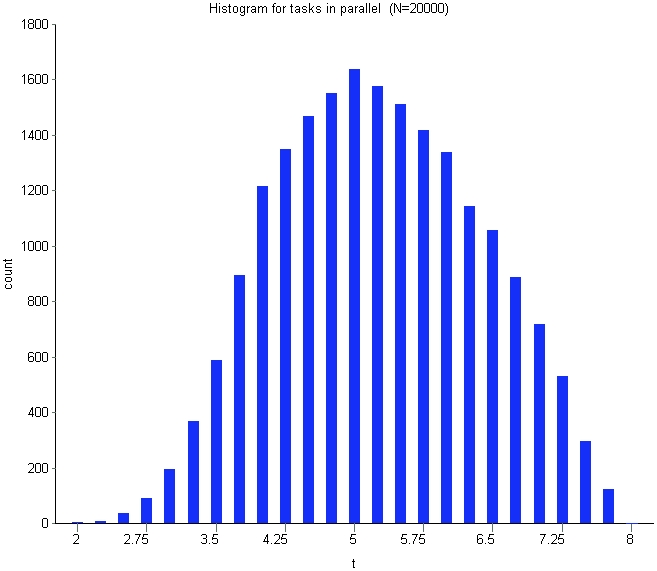

I looked at two cases: the first with no correlation between A and B and the second with a correlation of 0.79 between A and B. Each simulation consisted of 10,000 trials – basically I generated two sets of 10,000 triangularly-distributed random numbers, the first with a correlation coefficient close to zero and the second with a correlation coefficient of 0.79. Figures 2 and 3 depict scatter plots of the durations of A vs. the durations of B (for the same trial) for the uncorrelated and correlated cases. The correlation is pretty clear to see in Figure 3.

To check that the generated trials for A and B do indeed satisfy the triangular distribution, I divided the difference between the minimum and maximum times (for the individual tasks) into 0.5 day intervals and plotted the number of trials that fall into each interval. The resulting histograms are shown in Figure 4. Note that the blue and red bars are frequency plots for the case where A and B are uncorrelated and the green and pink (purple?) bars are for the case where they are correlated.

The histograms for all four cases are very similar, demonstrating that they all follow the specified triangular distribution. Figures 2 through 4 give confidence (but do not prove!) that Roxburgh’s utility works as advertised: i.e. that it generates sets of correlated random numbers in a way that preserves the desired distribution.

Now, to simulate A and B in sequence I simply added the durations of the individual tasks for each trial. I did this twice – once each for the correlated and uncorrelated data sets – which yielded two sets of completion times, varying between 4 days (the theoretical minimum) and 16 days (the theoretical maximum). As before, I plotted a frequency histogram for the uncorrelated and correlated case (see Figure 5). Note that the difference in the heights of the bars has no significance – it is an artefact of having the same number of trials (10,000) in both cases. What is significant is the difference in the spread of the two plots – the correlated case has a greater spread signifying an increased probability of very low and very high completion times compared to the uncorrelated case.

Note that the uncorrelated case resembles a Normal distribution – it is more symmetric than the original triangular distribution. This is a consequence of the Central Limit Theorem which states that the sum of identically distributed, independent (i.e. uncorrelated) random numbers is Normally distributed, regardless of the form of original distribution. The correlated distribution, on the other hand, has retained the shape of the original triangular distribution. This is no surprise: the relatively high correlation coefficient ensures that A and B will behave in a similar fashion and, hence, so will their sum.

Figure 6 is a plot of the cumulative distribution function (CDF) for the uncorrelated and correlated cases. The value of the CDFat any time gives the probability that the overall task will finish within time

.

The cumulative distribution clearly shows the greater spread in the correlated case: for small values of , the correlated distribution is significantly greater than the uncorrelated one; whereas for high values of

, the correlated distribution approaches the limiting value of 1 more slowly than the uncorrelated distribution. Both these factors point to a greater spread in the correlated case. The spread can be quantified by looking at the standard deviation of the two distributions. The standard deviation, often denoted by the small greek letter sigma (

), is given by:

wher is the total number of trials (10000),

is the completion time for the

th trial and

is the average completion time which is given by,

In both (2) and (3) denotes a sum over all trials.

The averages, , for the uncorrelated and correlated cases are virtually identical: 9.32 days and 9.34 days respectively. On the other hand, the standard deviations for the two cases are 1.77 and 2.34 respectively –demonstrating the wider spread in possible completion times for the correlated case. And, of course, a wider spread means greater uncertainty.

So, the simulations tell us that correlations increase uncertainty. Let’s try to understand why this happens. Basically, if tasks are correlated positively, they “track” each other: that is, if one takes a long time so will the other (with the same holding for short durations). The upshot of this is that the overall completion time tends to get “stretched” if the first task takes longer than average whereas it gets “compressed” if the first task finishes earlier than average. Since the net effect of stretching and compressing would balance out, we would expect the mean completion time (or any other measure of central tendency – such as the mode or median) to be relatively unaffected. However, because extremes are amplified, we would expect the spread of the distribution to increase.

Wrap-up

In this post I have highlighted the effect of task correlations on project schedules by comparing the results of simulations for two sequential tasks with and without correlations. The example shows that correlations can increase uncertainty. The mechanism is easy to understand: correlations tend to amplify extreme outcomes, thus increasing the spread in the resulting distribution. The effect of the correlation (compared to the uncorrelated case) can be quantified by comparing the standard deviations of the two cases.

Of course, quantifying correlations using a single number is simplistic – real life correlations have all kinds of complex dependencies. Nevertheless, it is a useful first step because it helps one develop an intuition for what might happen in more complicated cases: in hindsight it is easy to see that (positive) correlations will amplify extremes, but the simple model helped me really see it.

— —

Appendix – more on the Iman-Conover algorithm

Below I offer a hand-waving, half- explanation of how the technique works; those interested in a proper, technical explanation should see this paper by Simon Midenhall.

Before I launch off into my explanation, I’ll need to take a bit of a detour on coefficients of correlation. The title of Iman and Conover’s paper talks about rank correlation which is different from product-moment (or Pearson) correlation discussed in this post. A popular measure of rank correlation is the Spearman coefficient, , which is given by:

where is the rank difference between the duration of A and B on the

th instance of the project. Note that rank is calculated relative to all the other instances of a particular task (A or B). This is best explained through the table below, which shows the ranks for all instances of task A and B from my earlier example (columns 3 and 4).

| duration A (days) | duration B (days) | rank A | rank B | rank difference squared |

| 2.5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 7 | 7.5 | 10 | 10 | 0 |

| 6 | 4.5 | 8 | 5 | 9 |

| 5.5 | 3.5 | 7 | 3 | 16 |

| 4.5 | 4.5 | 5 | 5 | 0 |

| 5 | 5.5 | 6 | 9 | 9 |

| 4 | 4.5 | 4 | 5 | 1 |

| 6 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 0 |

| 3 | 3.5 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

Note that ties cause the subsequent number to be skipped.

The last column lists the rank differences, . The above can be used to calculate

, which works out to 0.776 – which is quite close to the Pearson coefficient calculated earlier (0.787). In practical terms, the Spearman coefficient is often considered to be an approximation to the Pearson coefficient.

With that background about the rank correlation, we can now move on to a brief discussion of the Iman-Conover algorithm.

In essence, the Iman-Conover method relies on reordering the set of to-be-correlated variables to have the same rank order as a reference distribution which has the desired correlation. To paraphrase from Midenhall’s paper (my two cents in italics):

Given two samples of n values from known distributions X and Y (the triangular distributions for A and B in this case) and a desired correlation between them (of 0.78), first determine a sample from a reference distribution that has exactly the desired linear correlation (of 0.78). Then re-order the samples from X and Y to have the same rank order as the reference distribution. The output will be a sample with the correct (individual, triangular) distributions and with rank correlation coefficient equal to that of the reference distribution…. Since linear (Pearson) correlation and rank correlation are typically close, the output has approximately the desired correlation structure…

The idea is beautifully simple, but a problem remains. How does one calculate the required reference distribution? Unfortunately, this is a fairly technical affair for which I could not find a simple explanation – those interested in a proper, technical discussion of the technique should see Chapter 4 of Midenhall’s paper or the original paper by Iman and Conover.

For completeness I should note that some folks have criticised the use of the Iman-Conover algorithm on the grounds that it generates rank correlated random variables instead of Pearson correlated ones. This is a minor technicality which does not impact the main conclusion of this post: i.e. that correlations increase uncertainty.

Monte Carlo simulation of multiple project tasks – three examples and some general comments

Introduction

In my previous post I demonstrated the use of a Monte Carlo technique in simulating a single project task with completion times described by a triangular distribution. My aim in that article was to: a) describe a Monte Carlo simulation procedure in enough detail for someone interested to be able to reproduce the calculations and b) show that it gives sensible results in a situation where the answer is known. Now it’s time to take things further. In this post, I present simulations for two tasks chained together in various ways. We shall see that, even with this small increase in complexity (from one task to two), the results obtained can be surprising. Specifically, small changes in inter-task dependencies can have a huge effect on the overall (two-task) completion time distribution. Although, this is something that that most project managers have experienced in real life, it is rarely taken in to account by traditional scheduling techniques. As we shall see, Monte Carlo techniques predict such effects as a matter of course.

Background

The three simulations discussed here are built on the example that I used in my previous article, so it’s worth spending a few lines for a brief recap of that example. The task simulated in the example was assumed to be described by a triangular distribution with minimum completion time () of 2 hours, most likely completion time (

) of 4 hours and a maximum completion time (

) of 8 hours. The resulting triangular probability distribution function (PDF),

– which gives the probability of completing the task at time t – is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 2 depicts the associated cumulative distribution function (CDF), which gives the probability that a task will be completed by time t (as opposed to the PDF which specifies the probability of completion at time t). The value of the CDF at t=8 is 1 because the task must finish within 8 hrs.

The equations describing the PDF and CDF are listed in equations 4-7 of my previous article. I won’t rehash them here as they don’t add anything new to the discussion – please see the article for all the gory algebraic details and formulas. Now, with that background, we’re ready to move on to the examples.

Two tasks in series with no inter-task delay

As a first example, let’s look at two tasks that have to be performed sequentially – i.e. the second task starts as soon as the first one is completed. To simplify things, we’ll also assume that they have identical (triangular) distributions as described earlier and shown in Figure 1 (excepting , of course, that the distribution is shifted to the right for the second task – since it starts after the first one finishes). We’ll also assume that the second task begins right after the first one is completed (no inter-task delay) – yes, this is unrealistic, but bear with me. The simulation algorithm for the combined tasks is very similar to the one for a single task (described in detail in my previous post). Here’s the procedure:

- For each of the two tasks, generate a set of N random numbers. Each random number generated corresponds to the cumulative probability of completion for a single task on that particular run.

- For each random number generated, find the time corresponding to the cumulative probability by solving equation 6 or 7 in my previous post.

- Step 2 gives N sets of completion times. Each set has two completion times – one for each tasks.

- Add up the two numbers in each set to yield the comple. The resulting set corresponds to N simulation runs for the combined task.

I then divided the time interval from t=4 hours (min possible completion time for both tasks) to t=16 hours (max possible completion time for both tasks) into bins of 0.25 hrs each, and then assigned each combined completion time to the appropriate bin. For example, if the predicted completion time for a particular run was 9.806532 hrs, it was assigned to the bin corresponding to 0.975 hrs. The resulting histogram is shown in Figure 3 below (click on image to view the full-size graphic).

[An aside: compare the histogram in Figure 3 to the one for a single task (Figure 1): the distribution for the single task is distinctly asymmetric (the peak is not at the centre of the distribution) whereas the two task histogram is nearly symmetric. This surprising result is a consequence of the Central Limit Theorem (CLT) – which states that the sum of many identical distributions tends to resemble the Normal (Bell-shaped) distribution, regardless of the shape of the individual distributions. Note that the CLT holds even though the two task distributions are shifted relative to each other – i.e. the second task begins after the first one is completed.]

The simulation also enables us to compute the cumulative probability of completion for the combined tasks (the CDF). This value of the cumulative probability at a particular bin equals the sum of the number of simulations runs in every bin up to (and including) the bin in question, divided by the total number of simulation runs. In mathematical terms this is:

where is the cumulative probability at the time corresponding to the

th bin,

, the number of simulation runs in the

th bin and

the total number of simulation runs. Note that this formula is an approximate one because time is treated as a constant within each bin. The approximation can be improved by making the bins smaller (and hence increasing the number of bins).

The resulting cumulative probability function is shown in Figure 4. This allows us to answer questions such as: “What is the probability that the tasks will be completed within 10 days?”. Answer: .698, or approximately 70%. (Note: I obtained this number by interpolating between values obtained from equation (1), but this level of precision is uncalled for, particularly because the formula is an approximate one)

Many project scheduling techniques compute average completion times for component tasks and then add them up to get the expected completion time for the combined task. In the present case the average works out to 9.33 hrs (twice the average for a single task). However, we see from the CDF that there is a significant probability (.43) that we will not finish by this time – and this in a “best-case ” situation where the second task starts immediately after the first one finishes!

[An aside: If one applies the well-known PERT formula to each of the tasks, one gets an expected completion time of 8.66 hrs for the combined task. From the CDF one can show that there is a probability of non-completion of 57% by t=8.66 hours (see Figure 4) – i.e. there’s a greater than even chance of not finishing by this time!]

As interesting as this case is, it is somewhat unrealistic because successor tasks seldom start the instant the predecessor is completed. More often than not, there is a cut-off time before which the successor cannot start – even if there are no explicit dependencies between the two tasks. This observation is a perfect segue into my next example, which is…

Two tasks in series with a fixed earliest start for the successor

Now we’ll introduce a slight complication: let’s assume, as before, that the two tasks are done one after the other but that the earliest the second task can start is at hours (as measured from the start of the first task). So, if the first task finishes within 6 hours, there will be a delay between its completion and the start of the second task. However, if the first task takes longer than 6 hours to finish, the second task will start soon after the first one finishes. The simulation procedure is the same as described in the previous section excepting for the last step – the completion time for the combined task is given by:

, for t

6 hrs and

, for t < 6 hrs

I divided the time interval from t=4hrs to t=20 hrs into bins of 0.25 hr duration (much as I did before) and then assigned each combined completion time to the appropriate bin. The resulting histogram is shown in Figure 5.

Comparing Figure 5 to Figure 3, we see that the earliest possible finish time now increases from 4 hrs to 8 hrs. This is no surprise, as we built this in to our assumption. Further, as one might expect, the distribution is distinctly asymmetric – with a minimum completion time of 8 hrs, a most likely time between 10 and 11 hrs and a maximum completion time of about 15 hrs.

Figure 6 shows the cumulative probability of completion for this case.

Because of the delay condition, it is impossible to calculate the average completion from the formulas for the triangular distribution – we have to obtain it from the simulation. The average can be calculated from the simulation adding up all completion times and dividing by the total number of simulations, . In mathematical terms this is:

where is the average time,

the completion time for the

th simulation run and

the total number of simulation runs.

This procedure gave me a value of about 10.8 hrs for the average. From the CDF in Figure 6 one sees that the probability that the combined task will finish by this time is only 0.60 – i.e. there’s only a 60% chance that the task will finish by this time. Any naïve estimation of time would do just as badly unless, of course, one is overly pessimistic and assumes a completion time of 15 – 16 hrs.

From the above it should be evident that the simulation allows one to associate an uncertainty (or probability) with every estimate. If management imposes a time limit of 10 hours, the project manager can refer to the CDF in Figure 6 and figure out the probability of completing the task by that time (there’s a 40 % chance of completion by 10 hrs). Of course, the reliability of the numbers depend on how good the distribution is. But the assumptions that have gone into the model are known – the optimistic, most likely and pessimistic times and the form of the distribution – and these can be refined as one gains experience.

Two tasks in parallel

My final example is the case of two identical tasks performed in parallel. As above, I’ll assume the uncertainty in each task is characterized by a triangular distribution with ,

and

of 2, 4 and 8 hours respectively. The simulation procedure for this case is the same as in the first example, excepting the last step. Assuming the simulated completion times for the individual tasks are

and

, the completion time for the combined tasks is given by the greater of the two – i.e. the combined completion time

is given by

.

To plot the histogram shown in Figure 7 , I divided the interval from t=2 hrs to t=8 hrs into bins of 0.25 hr duration each (Warning: Note the difference in the time axis scale from Figures 3 and 5!).

It is interesting to compare the above histogram with that for an individual task with the same parameters (i.e. the example that was used in my previous post). Figure 8 shows the histograms for the two examples on the same plot (the combined task in red and the single task in blue). As one might expect, the histogram for the combined task is shifted to the right, a consequence of the nonlinear condition on the completion time.

What about the average? I calculated the average as before, by using equation (2) from the previous section. This gives an average of 5.38 hrs (compared to 4.67 hrs for either task, taken individually). Note that the method to calculate the average is the same regardless of the form of the distribution. On the other hand, computing the average from the equations would be a complicated affair, involving a stiff dose of algebra with an optional sprinkling of calculus. Even worse – the calculations would vary from distribution to distribution. There’s no question that simulations are much easier.

The CDF for the overall completion time is also computed easily using equation (1). The resulting plot is shown in Figure 9 (Note the difference in the time axis scale from Figures 4 and 6!). There are no surprises here – excepting how easy it is to calculate once the simulation is done.

Let’s see what time corresponds to a 90% certainty of completion. A rough estimate for this number can be obtained from Figure 9 – just find the value of t (on the x axis) corresponding to a cumulative probability of 0.9 (on the y axis). This is the graphical equivalent of solving the CDF for time, given the cumulative probability is 0.9. From Figure 9, we get a time of approximately 6.7 hrs. [Note: we could get a more accurate number by fitting the points obtained from equation (1) to a curve and then calculating the time corresponding to ]. The interesting thing is that the 90% certain completion time is not too different from that of a single task (as calculated from equation 7 of my previous post) – which works out to 6.45 hrs.

Comparing the two histograms in Figure 8, we expect the biggest differences in cumulative probability to occur at about the t=4 hour mark, because by that time the probability for the individual task has peaked whereas that for the combined task is yet to peak. Let’s see if this is so: from Figure 8, the cumulative probability for t=4 hrs is about .15 and from the CDF for the triangular distribution (equation 6 from my previous post), the cumulative probability at t=4 hours (which is the most likely time) is .333 – double that of the combined task. This, again, isn’t too surprising (once one has Figure 8 on hand). The really nice thing is that we are able to attach uncertainties to all our estimates.

Conclusion

Although the examples discussed above are simple – two identical tasks with uncertainties described by a triangular distribution – they serve to illustrate some of the non-intuitive outcomes when tasks have dependencies. It is also worth noting that although the distribution for the individual tasks is known, the only straightforward way to obtain the distributions for the combined tasks (figures 3, 5 and 7) is through simulations. So, even these simple examples are a good demonstration of the utility of Monte Carlo techniques. Of course, real projects are way more complicated, with diverse tasks distributed in many different ways. To simplify simulations in such cases, one could perform coarse-grained simulations on a small number of high-level tasks, each consisting of a number of low-level, atomic tasks. The high-level tasks could be constructed in such a way as to focus attention on areas of greatest complexity, and hence greatest uncertainty.

As I have mentioned several times in this article and the previous one: simulation results are only as good as the distributions on which they are based. This begs the question: how do we know what’s an appropriate distribution for a given situation? There’s no one-size-fits-all answer to this question. However, for project tasks there are some general considerations that apply. These are:

- There is a minimum time (

) before which a task cannot cannot be completed.

- The probability will increase from 0 at

to a maximum at a “most likely” completion time,

. This holds true for most atomic tasks – but may be not for composite tasks which consist of many smaller tasks.

- The probability decreases as time increases beyond

, falling to 0 at a time much larger than

. This is simply another way of saying that the distribution has a long (but not necessarily infinite!) tail.

Asymmetric triangular distributions (such as the one used in my examples) are the simplest distributions that satisfy these conditions. Furthermore, a three point estimate is enought to specify a triangular distribution completely – i.e. given a three point estimate there is only one triangular distribution that can be fitted to it. That said, there are several other distributions that can be used; of particular relevance are certain long-tailed distributions.

Finally, I should mention that I make no claims about the efficiency or accuracy of the method presented here: it should be seen as a demonstration rather than a definitive technique. The many commercial Monte Carlo tools available in the market probably offer far more comprehensive, sophisticated and reliable algorithms (Note: I ‘ve never used any of them, so I can’t make any recommendations!). That said, it is always helpful to know the principles behind such tools, if for no other reason than to understand how they work and, more important, how to use them correctly. The material discussed in this and the previous article came out of my efforts to develop an understanding Monte Carlo techniques and how they can be applied to various aspects of project management (they can also be applied to cost estimation, for example). Over the last few weeks I’ve spent many enjoyable evenings developing and running these simulations, and learning from them. I’ll leave it here with the hope that you find my articles helpful in your own explorations of the wonderful world of Monte Carlo simulations.