Archive for the ‘General Management’ Category

On the anticipation of unintended consequences

A couple of weeks ago I bought an anthology of short stories entitled, An Exploration of Unintended Consequences, written by a school friend, Ajit Chaudhuri. I started reading and couldn’t stop until I got to the last page a couple of hours later. I’ll get to the book towards the end of this piece, but first, a rather long ramble about some thoughts which have been going around my head since I read it.

–x–

Many (most?) of the projects we undertake, or even the actions we perform, both at work and in our personal lives have unexpected side-effects or results that overshadow their originally intended outcomes. To be clear, unexpected does not necessarily mean adverse – consider, for example, Adam Smith’s invisible hand. However, it is also true – at least at the level of collectives (organisations or states) – that negative outcomes far outnumber positive ones. The reason this happens can be understood from a simple argument based on the notion of entropy – i.e., the fact that disorder is far more likely than order. Anyway, as interesting as that may be, it is tangential to the question I want to address in this post, which is:

Is it possible to plan and act in a way which anticipates, or even encourages, positive unintended consequences?

Let’s deal with the “unintended” bit first. And you may ask: does the question make sense? Surely, if an outcome is unintended, then it is necessarily unanticipated (let alone positive).

But is that really so? In this paper, Frank DeZwart, suggests it isn’t. In particular, he notes that, ” if unintended effects are anticipated, they are a different phenomenon as they follow from purposive choice and not, like unanticipated effects, from ignorance, error, or ideological blindness.”

As he puts it, “unanticipated consequences can only be unintended, but unintended consequences can be either anticipated or unanticipated.”

So the question posed earlier makes sense, and the key to answering it lies in understanding the difference between purposive and purposeful choice (or action).

–x–

In a classic paper that heralded the birth of cybernetics, Rosenblueth, Wiener and Bigelow noted that, “the term purposeful is meant to denote that the act or behavior may be interpreted as directed to the attainment of a goal-i.e., to a final condition in which the behaving object reaches a definite correlation in time or in space with respect to another object or event.”

Aside 1: The reader will notice that the definition has a decidedly scientific / engineering flavour. So, it is not surprising that philosophers jumped into the fray, and arguments around finer points of the definition ensued (see this sequence of papers, for example). Although interesting, we’ll ignore the debate as it will take us down a rabbit hole from which there is no return.

Aside 2: Interestingly, the Roseblueth-Wiener-Bigelow paper along with this paper by Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts laid the foundation for cybernetics. A little known fact is that the McCulloch-Pitts paper articulated the basic ideas behind today’s neural networks and Nobel Prize glory, but that’s another story.

Back to our quest: the Rosenblueth-Wiener definition of purposefulness has two assumptions embedded in it:

a) that the goal is well-defined (else, how will an actor know it has been achieved?), and

b) the actor is aware of the goal (else, how will an actor know what to aim for?)

We’ll come back to these in a bit, but let’s continue with the purposeful / purposive distinction first.

As I noted earlier, the cybernetic distinction between purposefulness and purposiveness led to much debate and discussion. Much of the difference of opinion arises from the ways in which diverse disciplines interpret the term. To avoid stumbling into that rabbit hole, I’ll stick to definitions of purposefulness / purposiveness from systems and management domains.

–x–

The first set of definitions is from a 1971 paper by Russell Ackoff in which he attempts to set out clear definitions of systems thinking concepts for management theorists and professionals.

Here are his definitions for purposive and purposeful systems:

“A purposive system is a multi-goal seeking system the different goals of which have a common property. Production of that property is the system’s purpose. These types of systems can pursue different goals, but they do not select the goal to be pursued. The goal is determined by the initiating event. But such a system does choose the means by which to pursue its goals.”

and

“A purposeful system is one which can produce the same outcome in different ways…[and] can change its goals under constant conditions – it selects ends as well as means and thus displays will. Human beings are the most familiar examples of such systems.”

Ackoff’s purpose(!) in making the purposive/purposeful distinction was to clarify the difference between apparent purpose displayed by machines (computers) which he calls purposiveness, and “true” or willed (or human) purpose which he calls purposefulness. Although this seems like a clear cut distinction, it falls apart on closer inspection. The example Ackoff gives for a purposive system is that of a computer which is programmed to play multiple games – say noughts-and-crosses and checkers. The goal differs depending on which game it plays, but the common property is winning. However, this feels like an artificial distinction: surely winning is a goal, albeit a higher-order one.

–x–

The second set of definitions, due to Peter Checkland, is taken from this module from an Open University course on managing complexity:

“Two forms of behaviour in relation to purpose have also been distinguished. One is purposeful behaviour, which [can be described] as behaviour that is willed – there is thus some sense of voluntary action. The other is purposive behaviour – behaviour to which an observer can attribute purpose. Thus, in the example of the government minister, if I described his purpose as meeting some political imperative, I would be attributing purpose to him and describing purposive behaviour. I might possibly say his intention was to deflect the issue for political reasons. Of course, if I were to talk with him I might find out this was not the case at all. He might have been acting in a purposeful manner which was not evident to me.”

This distinction is strange because the definitions of the two terms are framed from two different perspectives – that of an actor and that of an observer. Surely, when one makes a distinction, one should do so from a single perspective.

…and yet, there is something in this perspective shift which I’ll come back to in a bit.

–x–

The third set of definitions is from Robert Chia and Robin Holt’s classic, Strategy Without Design: The Silent Efficacy of Indirect Action:

“Purposive action is action taken to alleviate ourselves from a negative situation we find ourselves in. In everyday engagements, we might act to distance ourselves from an undesirable situation we face, but this does not imply having a pre-established end goal in mind. It is a moving away from rather than a moving towards that constitutes purposive actions. Purposeful actions, on the other hand, presuppose having a desired and clearly articulated end goal that we aspire towards. It is a product of deliberate intention“

Finally, here is a distinction we can work with:

- Purposive actions are aimed at alleviating negative situations (note, this can be framed in a better way, and I’ll get to that shortly)

- Purposeful actions are those aimed at achieving a clearly defined goal.

The interesting thing is that the above definition of purposive action is consistent with the two observations I made earlier regarding the original Rosenbluth-Wiener-Bigelow definition of purposeful systems

a) purposive actions have no well-defined end-state (alleviating a negative situation says nothing about what the end-state will look like). That said, someone observing the situation could attribute purpose to the actor because the behaviour appears to be purposeful (see Checkland’s definition above).

b) as the end-state is undefined, the purposive actor cannot know it. However, this need not stop the actor from envisioning what it ought to look like (and indeed, most purposive actors will).

In a later paper Chia, wrote, , “…[complex transformations require] an implicit awareness that the potentiality inherent in a situation can be exploited to one’s advantage without adverse costs in terms of resources. Instead of setting out a goal for our actions, we could try to discern the underlying factors whose inner configuration is favourable to the task at hand and to then allow ourselves to be carried along by the momentum and propensity of things.”

Inspired by this, I think it is appropriate to reframe the Chia-Holt definition more positively, by rephrasing it as follows:

“Purposive action is action which exploits the inherent potential in a situation so as to increase the likelihood of positive outcomes for those who have a stake in the situation”

The above statement includes the Chia-Holt definition as such an action could be a moving away from a negative situation. However, it could also be an action that comes from recognising an opportunity that would otherwise remain unexploited.

–x–

And now, I can finally answer the question I raised at the start regarding anticipated unintended consequences. In brief:

A purposive action, as I have defined above, is one that invariably leads to anticipated unintended consequences.

Moreover, its consequences are often (usually?) positive, even though the specific outcomes are generally impossible to articulate at the start.

Purposive action is at the heart of emergent design, which is based on doing things that increase the probability of organisational success, but in an unobtrusive manner which avoids drawing attention. Examples of such low-key actions based on recognising the inherent potential of situations are available in the Chia-Holt book referenced above and in the book I wrote with Alex Scriven.

I should also point out that since purposive action involves recognising the potential of an unfolding situation, there is necessarily an improvisational aspect to it. Moreover, since this potential is typically latent and not obvious to all stakeholders, the action should be taken in a way that does not change the dynamics of the situation. This is why oblique or indirect actions tend to work better than highly visible, head-on ones. Developing the ability to act in such a manner is more about cultivating a disposition that tolerates ambiguity than learning to follow prescribed rules, models or practices.

–x–

So much for purposive action at the level of collectives. Does it, can it, play a role in our individual lives?

The short answer is: yes it can. A true story might help clarify:

“I can’t handle failure,” she said. “I’ve always been at the top of my class.”

She was being unduly hard on herself. With little programming experience or background in math, machine learning was always going to be hard going. “Put that aside for now,” I replied. “Just focus on understanding and working your way through it, one step at a time. In four weeks, you’ll see the difference.”

“OK,” she said, “I’ll try.”

She did not sound convinced but to her credit, that’s exactly what she did. Two months later she completed the course with a distinction.

“You did it!” I said when I met her a few weeks after the grades were announced.

“I did,” she grinned. “Do you want to know what made the difference?”

Yes, I nodded.

“Thanks to your advice, I stopped treating it like a game I had to win,” she said, “and that took the pressure right off. I then started to enjoy learning.”

–x–

And this, finally, brings me back to the collection of short stories written by my friend Ajit. The stories are about purposive actions taken by individuals and their unintended consequences. Consistent with my discussion above, the specific outcomes in the stories could not have been foreseen by the protagonists (all women, by the way), but one can well imagine them thinking that their actions would eventually lead to a better place.

That aside, the book is worth picking up because the author is a brilliant raconteur: his stories are not only entertaining, they also give readers interesting insights into everyday life in rural and urban India. The author’s note at the end gives some background information and further reading for those interested in the contexts and settings of the stories.

I found Ajit’s use of inset stories – tales within tales – brilliant. The anthropologist, Mary Catherine Bateson, once wrote, “an inset story is a standard hypnotic device, a trance induction device … at the most obvious level, if we are told that Scheherazade told a tale of fantasy, we are tempted to believe that she, at least, is real.” Ajit uses this device to great effect.

Finally, to support my claim that the stories are hugely entertaining, here are a couple of direct quotes from the book:

The line “Is there anyone here at this table who, deep down, does not think that her husband is a moron?” had me laughing out loud. My dear wife asked me what’s up. I told her; she had a good laugh too, and from the tone of her laughter, it was clear she agreed.

Another one: “…some days I’m the pigeon and some days I’m the statue. It’s just that on the days that I’m the pigeon, I try to remember what it is like to be the statue. And on the days that I’m the statue, I try not to think.” Great advice, which I’ve passed on to my two boys.

–x–

I called Ajit the other day and spoke to him for the first time in over 40 years; another unintended consequence of reading his book.

–x—x–

The two tributaries of time

How time flies. Ten years ago this month, I wrote my first post on Eight to Late. The anniversary gives me an excuse to post something a little different. When rummaging around in my drafts folder for something suitable, I came across this piece that I wrote some years ago (2013) but didn’t publish. It’s about our strange relationship with time, which I thought makes it a perfect piece to mark the occasion.

Introduction

The metaphor of time as a river resonates well with our subjective experiences of time. Everyday phrases that evoke this metaphor include the flow of time and time going by, or the somewhat more poetic currents of time. As Heraclitus said, no [person] can step into the same river twice – and so it is that a particular instant in time …like right now…is ephemeral, receding into the past as we become aware of it.

On the other hand, organisations have to capture and quantify time because things have to get done within fixed periods, the financial year being a common example. Hence, key organisational activities such as projects, strategies and budgets are invariably time-bound affairs. This can be problematic because there is a mismatch between the ways in which organisations view time and individuals experience it.

Organisational time

The idea that time is an objective entity is most clearly embodied in the notion of a timeline: a graphical representation of a time period, punctuated by events. The best known of these is perhaps the ubiquitous Gantt Chart, loved (and perhaps equally, reviled) by managers the world over.

Timelines are interesting because, as Elaine Yakura states in this paper, “they seem to render time, the ultimate abstraction, visible and concrete.” As a result, they can serve as boundary objects that make it possible to negotiate and communicate what is to be accomplished in the specified time period. They make this possible because they tell a story with a clear beginning, middle and end, a narrative of what is to come and when.

For the reasons mentioned in the previous paragraph, timelines are often used to manage time-bound organisational initiatives. Through their use in scheduling and allocation, timelines serve to objectify time in such a way that it becomes a resource that can be measured and rationed, much like other resources such as money, labour etc.

At our workplaces we are governed by many overlapping timelines – workdays, budgeting cycles and project schedules being examples. From an individual perspective, each of these timelines are different representations of how one’s time is to be utilised, when an activity should be started and when it must be finished. Moreover, since we are generally committed to multiple timelines, we often find ourselves switching between them. They serve to remind us what we should be doing and when.

But there’s more: one of the key aims of developing a timeline is to enable all stakeholders to have a shared understanding of time as it pertains to the initiative. In this view, a timeline is a consensus representation of how a particular aspect of the future will unfold. Timelines thus serve as coordinating mechanisms.

In terms of the metaphor, a timeline is akin to a map of the river of time. Along the map we can measure out and apportion it; we can even agree about way-stops at various points in time. However, we should always be aware that it remains a representation of time, for although we might treat a timeline as real, the fact is no one actually experiences time as it is depicted in a timeline. Mistaking one for the other is akin to confusing the map with the territory.

This may sound a little strange so I’ll try to clarify. I’ll start with the observation that we experience time through events and processes – for example the successive chimes of a clock, the movement of the second hand of a watch (or the oscillations of a crystal), the passing of seasons or even the greying of one’s hair. Moreover, since these events and processes can be objectively agreed on by different observers, they can also be marked out on a timeline. Yet the actual experience of living these events is unique to each individual.

Individual perception of time

As we have seen, organisations treat time as an objective commodity that can be represented, allocated and used much like any tangible resource. On the other hand our experience of time is intensely personal. For example, I’m sitting in a cafe as I write these lines. My perception of the flow of time depends rather crucially on my level of engagement in writing: slow when I’m struggling for words but zipping by when I’m deeply involved. This is familiar to us all: when we are deeply engaged in an activity, we lose all sense of time but when our involvement is superficial we are acutely aware of the clock.

This is true at work as well. When I’m engaged in any kind of activity at work, be it a group activity such as a meeting, or even an individual one such as developing a business case, my perception of time has little to do with the actual passage of seconds, minutes and hours on a clock. Sure, there are things that I will do habitually at a particular time – going to lunch, for example – but my perception of how fast the day goes is governed not by the clock but by the degree of engagement with my work.

I can only speak for myself, but I suspect that this is the case with most people. Though our work lives are supposedly governed by “objective” timelines, the way we actually live out our workdays depends on a host of things that have more to do with our inner lives than visible outer ones. Specifically, they depend on things such as feelings, emotions, moods and motivations.

Flow and engagement

OK, so you may be wondering where I’m going with this. Surely, my subjective perception of my workday should not matter as long as I do what I’m required to do and meet my deadlines, right?

As a matter of fact, I think the answer to the above question is a qualified, “No”. The quality of the work we do depends on our level of commitment and engagement. Moreover, since a person’s perception of the passage of time depends rather sensitively on the degree of their involvement in a task, their subjective sense of time is a good indicator of their engagement in work.

In his book, Finding Flow, Mihalyi Csikszentmihalyi describes such engagement as an optimal experience in which a person is completely focused on the task at hand. Most people would have experienced flow when engaged in activities that they really enjoy. As Anthony Reading states in his book, Hope and Despair: How Perceptions of the Future Shape Human Behaviour, “…most of what troubles us resides in our concerns about the past and our apprehensions about the future.” People in flow are entirely focused on the present and are thus (temporarily) free from troubling thoughts. As Csikszentmihalyi puts it, for such people, “the sense of time is distorted; hours seem to pass by in minutes.”

All this may seem far removed from organisational concerns, but it is easy to see that it isn’t: a Google search on the phrase “increase employee engagement” will throw up many articles along the lines of “N ways to increase employee engagement.” The sense in which the term is used in these articles is essentially the same as the one Csikszentmihalyi talks about: deep involvement in work.

So, the advice of management gurus and business school professors notwithstanding, the issue is less about employee engagement or motivation than about creating conditions that are conducive to flow. All that is needed for the latter is a deep understanding how the particular organisation functions, the task at hand and (most importantly) the people who will be doing it. The best managers I’ve worked with have grokked this, and were able to create the right conditions in a seemingly effortless and unobtrusive way. It is a skill that cannot be taught, but can be learnt by observing how such managers do what they do.

Time regained

Organisations tend to treat their employees’ time as though it were a commodity or resource that can be apportioned and allocated for various tasks. This view of time is epitomised by the timeline as depicted in a Gantt Chart or a resource-loaded project schedule.

In contrast, at an individual level, the perception of time depends rather critically on the level of engagement that a person feels with the task he or she is performing. Ideally organisations would (or ought to!) want their employees to be in that optimal zone of engagement that Csikszentmihalyi calls flow, at least when they are involved in creative work. However, like spontaneity, flow is a state that cannot be achieved by corporate decree; the best an organisation can do is to create the conditions that encourage it.

The organisational focus on timelines ought to be balanced by actions that are aimed at creating the conditions that are conducive to employee engagement and flow. It may then be possible for those who work in organisation-land to experience, if only fleetingly, that Blakean state in which eternity is held in an hour.

Uncertainty, ambiguity and the art of decision making

A common myth about decision making in organisations is that it is, by and large, a rational process. The term rational refers to decision-making methods that are based on the following broad steps:

- Identify available options.

- Develop criteria for rating options.

- Rate options according to criteria developed.

- Select the top-ranked option.

Although this appears to be a logical way to proceed it is often difficult to put into practice, primarily because of uncertainty about matters relating to the decision.

Uncertainty can manifest itself in a variety of ways: one could be uncertain about facts, the available options, decision criteria or even one’s own preferences for options.

In this post, I discuss the role of uncertainty in decision making and, more importantly, how one can make well-informed decisions in such situations.

A bit about uncertainty

It is ironic that the term uncertainty is itself vague when used in the context of decision making. There are at least five distinct senses in which it is used:

- Uncertainty about decision options.

- Uncertainty about one’s preferences for options.

- Uncertainty about what criteria are relevant to evaluating the options.

- Uncertainty about what data is needed (data relevance).

- Uncertainty about the data itself (data accuracy).

Each of these is qualitatively different: uncertainty about data accuracy (item 5 above) is very different from uncertainty regarding decision options (item 1). The former can potentially be dealt with using statistics whereas the latter entails learning more about the decision problem and its context, ideally from different perspectives. Put another way, the item 5 is essentially a technical matter whereas item 1 is a deeper issue that may have social, political and – as we shall see – even behavioural dimensions. It is therefore reasonable to expect that the two situations call for vastly different approaches.

Quantifiable uncertainty

A common problem in project management is the estimation of task durations. In this case, what’s requested is a “best guess” time (in hours or days) it will take to complete a task. Many project schedules represent task durations by point estimates, i.e. by single numbers. The Gantt Chart shown in Figure 1 is a common example. In it, each task duration is represented by its expected duration. This is misleading because the single number conveys a sense of certainty that is unwarranted. It is far more accurate, not to mention safer, to quote a range of possible durations.

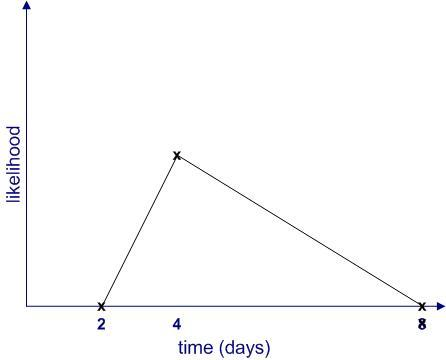

In general, quantifiable uncertainties, such as those conveyed in estimates, should always be quoted as ranges – something along the following lines: task A may take anywhere between 2 and 8 days, with a most likely completion time of 4 days (Figure 2).

In this example, aside from stating that the task will finish sometime between 2 and 4 days, the estimator implicitly asserts that the likelihood of finishing before 2 days or after 8 days is zero. Moreover, she also implies that some completion times are more likely than others. Although it may be difficult to quantify the likelihood exactly, one can begin by making simple (linear!) approximations as shown in Figure 3.

The key takeaway from the above is that quantifiable uncertainties are shapes rather than single numbers. See this post and this one for details for how far this kind of reasoning can take you. That said, one should always be aware of the assumptions underlying the approximations. Failure to do so can be hazardous to the credibility of estimators!

Although I haven’t explicitly said so, estimation as described above has a subjective element. Among other things, the quality of an estimate depends on the judgement and experience of the estimator. As such, it is prone to being affected by errors of judgement and cognitive biases. However, provided one keeps those caveats in mind, the probability-based approach described above is suited to situations in which uncertainties are quantifiable, at least in principle. That said, let’s move on to more complex situations in which uncertainties defy quantification.

Introducing ambiguity

The economist Frank Knight was possibly the first person to draw the distinction between quantifiable and unquantifiable uncertainties. To make things really confusing, he called the former risk and the latter uncertainty. In his doctoral thesis, published in 1921, wrote:

…it will appear that a measurable uncertainty, or “risk” proper, as we shall call the term, is so far different from an unmeasurable one that it is not in effect an uncertainty at all. We shall accordingly restrict the term “uncertainty” to cases of the non-quantitative type (p.20)

Terminology has moved on since Knight’s time, the term uncertainty means lots of different things, depending on context. In this piece, we’ll use the term uncertainty to refer to quantifiable uncertainty (as in the task estimate of the previous section) and use ambiguity to refer to non–quantifiable uncertainty. In essence, then, we’ll use the term uncertainty for situations where we know what we’re measuring (i.e. the facts) but are uncertain about its numerical or categorical values whereas we’ll use the word ambiguity to refer to situations in which we are uncertain about what the facts are or which facts are relevant.

As a test of understanding, you may want to classify each of the five points made in the second section of this post as either uncertain or ambiguous (Answers below)

Answer: 1 through 4 are ambiguous and 5 is uncertain.

How ambiguity manifests itself in decision problems

The distinction between uncertainty and ambiguity points to a problem with quantitative decision-making techniques such as cost-benefit analysis, multicriteria decision making methods or analytic hierarchy process. All these methods assume that decision makers are aware of all the available options, their preferences for them, the relevant evaluation criteria and the data needed. This is almost never the case for consequential decisions. To see why, let’s take a closer look at the different ways in which ambiguity can play out in the rational decision making process mentioned at the start of this article.

- The first step in the process is to identify available options. In the real world, however, options often cannot be enumerated or articulated fully. Furthermore, as options are articulated and explored, new options and sub-options tend to emerge. This is particularly true if the options depend on how future events unfold.

- The second step is to develop criteria for rating options. As anyone who has been involved in deciding on a contentious issue will confirm, it is extremely difficult to agree on a set of decision criteria for issues that affect different stakeholders in different ways. Building a new road might improve commute times for one set of stakeholders but result in increased traffic in a residential area for others. The two criteria will be seen very differently by the two groups. In this case, it is very difficult for the two groups to agree on the relative importance of the criteria or even their legitimacy. Indeed, what constitutes a legitimate criterion is a matter of opinion.

- The third step is to rate options. The problem here is that real-world options often cannot be quantified or rated in a meaningful way. Many of life’s dilemmas fall into this category. For example, a decision to accept or decline a job offer is rarely made on the basis of material gain alone. Moreover, even where ratings are possible, they can be highly subjective. For example, when considering a job offer, one candidate may give more importance to financial matters whereas another might consider lifestyle-related matters (flexi-hours, commuting distance etc.) to be paramount. Another complication here is that there may not be enough information to settle the matter conclusively. As an example, investment decisions are often made on the basis of quantitative information that is based on questionable assumptions.

A key consequence of the above is that such ambiguous decision problems are socially complex – i.e. different stakeholders could have wildly different perspectives on the problem itself. One could say the ambiguity experienced by an individual is compounded by the group.

Before going on I should point out that acute versions of such ambiguous decision problems go by many different names in the management literature. For example:

- Horst Rittel called them wicked problems..

- Russell Ackoff referred to them as messes.

- Herbert Simon labelled them non-programmable problems.

All these terms are more or less synonymous: the root cause of the difficulty in every case is ambiguity (or unquantifiable uncertainty), which prevents a clear formulation of the problem.

Social complexity is hard enough to tackle as it is, but there’s another issue that makes things even harder: ambiguity invariably triggers negative emotions such as fear and anxiety in individuals who make up the group. Studies in neuroscience have shown that in contrast to uncertainty, which evokes logical responses in people, ambiguity tends to stir up negative emotions while simultaneously suppressing the ability to think logically. One can see this playing out in a group that is debating a contentious decision: stakeholders tend to get worked up over issues that touch on their values and identities, and this seems to limit their ability to look at the situation objectively.

Tackling ambiguity

Summarising the discussion thus far: rational decision making approaches are based on the assumption that stakeholders have a shared understanding of the decision problem as well as the facts and assumptions around it. These conditions are clearly violated in the case of ambiguous decision problems. Therefore, when confronted with a decision problem that has even a hint of ambiguity, the first order of the day is to help the group reach a shared understanding of the problem. This is essentially an exercise in sensemaking, the art of collaborative problem formulation. However, this is far from straightforward because ambiguity tends to evoke negative emotions and attendant defensive behaviours.

The upshot of all this is that any approach to tackle ambiguity must begin by taking the concerns of individual stakeholders seriously. Unless this is done, it will be impossible for the group to coalesce around a consensus decision. Indeed, ambiguity-laden decisions in organisations invariably fail when they overlook concerns of specific stakeholder groups. The high failure rate of organisational change initiatives (60-70% according to this Deloitte report) is largely attributable to this point

There are a number of techniques that one can use to gather and synthesise diverse stakeholder viewpoints and thus reach a shared understanding of a complex or ambiguous problem. These techniques are often referred to as problem structuring methods (PSMs). I won’t go into these in detail here; for an example check out Paul Culmsee’s articles on dialogue mapping and Barry Johnson’s introduction to polarity management. There are many more techniques in the PSM stable. All of them are intended to help a group reconcile different viewpoints and thus reach a common basis from which one can proceed to the next step (i.e., make a decision on what should be done). In other words, these techniques help reduce ambiguity.

But there’s more to it than a bunch of techniques. The main challenge is to create a holding environment that enables such techniques to work. I am sure readers have been involved in a meeting or situation where the outcome seems predetermined by management or has been undermined by self- interest. When stakeholders sense this, no amount of problem structuring is going to help. In such situations one needs to first create the conditions for open dialogue to occur. This is precisely what a holding environment provides.

Creating such a holding environment is difficult in today’s corporate world, but not impossible. Note that this is not an idealist’s call for an organisational utopia. Rather, it involves the application of a practical set of tools that address the diverse, emotion-laden reactions that people often have when confronted with ambiguity. It would take me too far afield to discuss PSMs and holding environments any further here. To find out more, check out my papers on holding environments and dialogue mapping in enterprise IT projects, and (for a lot more) the Heretic’s Guides that I co-wrote with Paul Culmsee.

The point is simply this: in an ambiguous situation, a good decision – whatever it might be – is most likely to be reached by a consultative process that synthesises diverse viewpoints rather than by an individual or a clique. However, genuine participation (the hallmark of a holding environment) in such a process will occur only after participants’ fears have been addressed.

Wrapping up

Standard approaches to decision making exhort managers and executives to begin with facts, and if none are available, to gather them diligently prior to making a decision. However, most real-life decisions are fraught with uncertainty so it may be best to begin with what one doesn’t know, and figure out how to make the possible decision under those “constraints of ignorance.” In this post I’ve attempted to outline what such an approach would entail. The key point is to figure out the kind uncertainty one is dealing with and choosing an approach that works for it. I’d argue that most decision making debacles stem from a failure to appreciate this point.

Of course, there’s a lot more to this approach than I can cover in the span of a post, but that’s a story for another time.

Note: This post is written as an introduction to the Data and Decision Making subject that is part of the core curriculum of the Master of Data Science and Innovation program at UTS. I’m co-teaching the subject in Autumn 2018 with Rory Angus and Alex Scriven.