Archive for the ‘Issue Based Information System’ Category

Mapping project dialogues using IBIS – a paper preview

Work commitments have conspired to keep this post short. Well, short compared to my usual long-winded essays at any rate. Among other things, I’m currently helping get a biggish project started while also trying to finish my current writing commitments in whatever little free time I have. Fortunately, I have a ready-made topic to write about this week: my recently published paper on the use of dialogue mapping in project management. Instead of summarizing the paper, as I usually do in my paper reviews, I’ll simply present some background to the paper and describe, in brief, my rationale for writing it.

As regular readers of this blog will know, I am a fan of dialogue mapping, a conversation mapping technique pioneered by Jeff Conklin. Those unfamiliar with the technique will find a super-quick introduction here. Dialogue mapping uses a visual notation called issue based information system (IBIS) which I have described in detail in this post. IBIS was invented by Horst Rittel as a means to capture and clarify facets of wicked problems – problems that are hard to define, let alone solve. However, as I discuss in the paper, the technique also has utility in the much more mundane day-to-day business of managing projects.

In essence, IBIS provides a means to capture questions, responses to questions and arguments for and against those responses. This, coupled with the fact that it is easy to use, makes it eminently suited to capturing conversations in which issues are debated and resolved. Dialogue mapping is therefore a great way to surface options, debate them and reach a “best for group” decision in real-time. The technique thus has many applications in organizational settings. I have used it regularly in project meetings, particularly those in which critical decisions regarding design or approach are being discussed.

Early last year I used the technique to kick-start a data warehousing initiative within the organisation I work for. In the paper I use this experience as a case-study to illustrate some key aspects and features of dialogue mapping that make it useful in project discussions. For completeness I also discuss why other visual notations for decision and design rationale don’t work as well as IBIS for capturing conversations in real-time. However, the main rationale for the paper is to provide a short, self-contained introduction to the technique via a realistic case-study.

Most project managers would have had to confront questions such as “what approach should we take to solve this problem?” in situations where there is not enough information to make a sound decision. In such situations, the only recourse one has is to dialogue – to talk it over with the team, and thereby reach a shared understanding of the options available. More often than not, a consensus decision emerges from such dialogue. Such a decision would be based on the collective knowledge of the team, not just that of an individual. Dialogue mapping provides a means to get to such a collective decision.

Capturing decision rationale on projects

Introduction

Most knowledge management efforts on projects focus on capturing what or how rather than why. That is, they focus on documenting approaches and procedures rather than the reasons behind them. This often leads to a situation where folks working on subsequent projects (or even the same project!) are left wondering why a particular technique or approach was favoured over others. How often have you as a project manager asked yourself questions like the following when browsing through a project archive?

- Why did project decision-makers choose to co-develop the system rather than build it in-house or outsource it?

- Why did the developer responsible for a module use this approach rather than that one?

More often than not, project archives are silent on such matters because the reasoning behind decisions isn’t documented. In this post I discuss how the Issue Based Information System (IBIS) notation can be used to fill this “rationale gap” by capturing the reasoning behind project decisions.

Note: Those unfamiliar with IBIS may want to have a browse of my post on entitled what and whence of issue-based information systems for a quick introduction to the notation and its uses. I also recommend downloading and installing Compendium, a free software tool that can be used to create IBIS maps.

Example 1: Build or outsource?

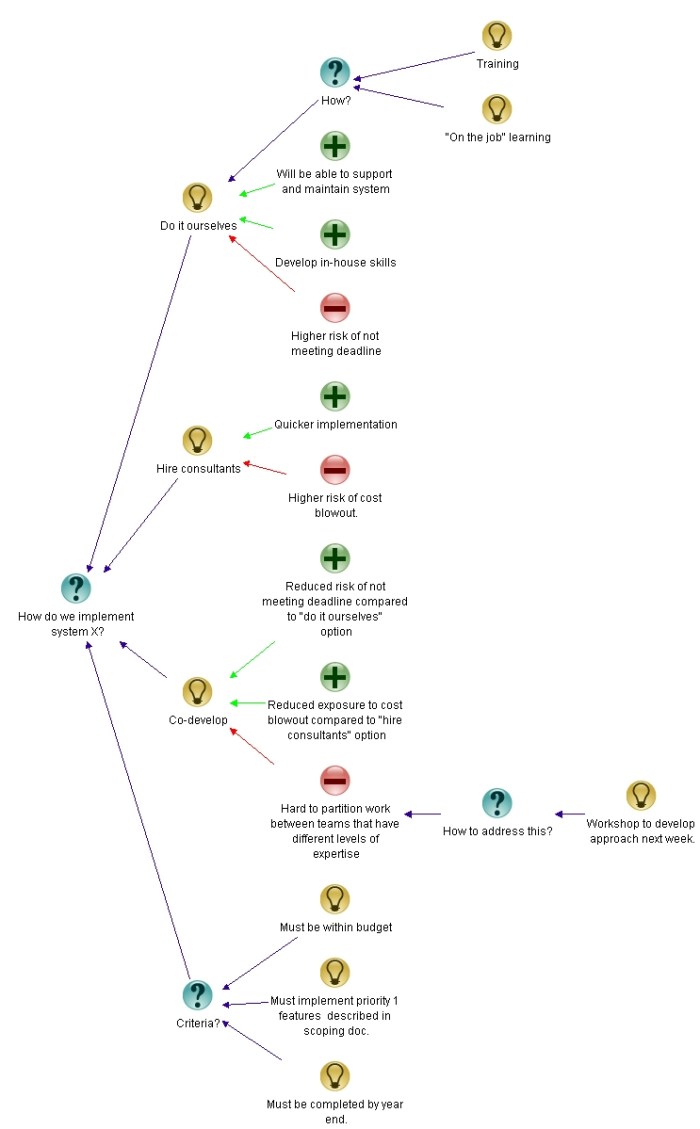

In a post entitled The Approach: A dialogue mapping story, I presented a fictitious account of how a project team member constructed an IBIS map of a project discussion (Note: dialogue mapping refers to the art of mapping conversations as they occur). The issue under discussion was the approach that should be used to build a system.

The options discussed by the team were:

- Build the system in-house.

- Outsource system development.

- Co-develop using a mix of external and internal staff.

Additionally, the selected approach had to satisfy the following criteria:

- Must be within a specified budget.

- Must implement all features that have been marked as top priority.

- Must be completed within a specified time

The post details how the discussion was mapped in real-time. Here I’ll simply show the final map of the discussion (see Figure 1).

Although the option chosen by the group is not marked (they chose to co-develop), the figure describes the pros and cons of each approach (and elaborations of these) in a clear and easy-to-understand manner. In other words, it maps the rationale behind the decision – a person looking at the map can get a sense for why the team chose to co-develop rather than use any of the other approaches.

Example 2: Real-time updates of a data mart

In another post on dialogue mapping I described how IBIS was used to map a technical discussion about the best way to update selected tables in a data mart during business hours. For readers who are unfamiliar with the term: data marts are databases that are (generally) used purely for reporting and analysis. They are typically updated via batch processes that are run outside of normal business hours. The requirement to do real-time updates arose from a business need to see up-to-the-minute reports at specified times during the financial year.

Again, I’ll refer the reader to the post for details, and simply present the final map (see Figure 2).

Since there are a few technical terms involved, here’s a brief rundown of the options, lifted straight from my earlier post (Note: feel free skip this detail – it is incidental to the main point of this post) :

- Use our messaging infrastructure to carry out the update.

- Write database triggers on transaction tables. These triggers would update the data mart tables directly or indirectly.

- Write custom T-SQL procedures (or an SSIS package) to carry out the update (the database is SQL Server 2005).

- Run the relevant (already existing) Extract, Transform, Load (ETL) procedures at more frequent intervals – possibly several times during the day.

In this map the option chosen by the group decision is marked out – it was decided that no additional development was needed; the “real-time” requirement could be satisfied simply by running existing update procedures during business hours (option 4 listed above).

Once again, the reasoning behind the decision is easy to see: the option chosen offered the simplest and quickest way to satisfy the business requirement, even though the update was not really done in real-time.

Summarising

The above examples illustrate how IBIS captures the reasoning behind project decisions. It does so by:

- Making explicit all the options considered.

- Describing the pros and cons of each option (and elaborations thereof).

- Providing a means to explicitly tag an option as a decision.

- Optionally, providing a means to link out to external source (documents, spreadsheets, urls). In the second example I could have added clickable references to documents elaborating on technical detail using the external link capability of Compendium.

Issue maps (as IBIS maps are sometimes called) lay out the reasoning behind decisions in a visual, easy-to-understand way. The visual aspect is important – see this post for more on why visual representations of reasoning are more effective than prose.

I’ve used IBIS to map discussions ranging from project approaches to mathematical model building, and have found them to be invaluable when asked questions about why things were done in a certain way. Just last week, I was able to answer a question about variables used in a market segmentation model that I built almost two years ago – simply by referring back to the issue map of the discussion and the notes I had made in it.

In summary: IBIS provides a means to capture decision rationale in a visual and easy-to-understand way, something that is hard to do using other means.

Making sense of sensemaking – the dimensions of participatory design rationale

Introduction

Over the last year or so, I’ve used IBIS (Issue-Based Information System) to map a variety of discussions at work, ranging from design deliberations to project meetings [Note: see this post for an introduction to IBIS and this one for an example of mapping dialogues using IBIS]. Feedback from participants indicated that IBIS helps to keep the discussion focused on the key issues, thus leading to better outcomes and decisions. Some participants even took the time to learn the notation (which doesn’t take long) and try it out in their own meetings. Yet, despite their initial enthusiasm, most of them gave it up after a session or two. Their reasons are well summed up by a colleague who said, “It is just too hard to build a coherent map on the fly while keeping track of the discussion.”

My colleague’s comment points to a truth about the technique: the success of a sense-making session depends rather critically on the skill of the practitioner. The question is: how do experienced practitioners engage their audience and build a coherent map whilst keeping the discussion moving in productive directions? Al Selvin, Simon Buckingham-Shum and Mark Aakhus provide a part answer to this question in their paper entitled, The Practice Level in Participatory Design Rationale : Studying Practitioner Moves and Choices. Specifically, they describe a general framework within which the practice of participatory design rationale (PDR) can be analysed (Note: more on PDR in the next section). This post is a discussion of some aspects of the framework and some personal reflections based on my (limited) experience.

A couple of caveats are in order before I proceed. Firstly, my discussion focuses on understanding the dimensions (or variables) that describe the act of creating design representations in real-time. Secondly, my comments and reflections on the model are based on my experiences with a specific design rationale technique – IBIS.

Background

First up, it is worth clarifying the meaning of participatory design rationale (PDR). The term refers to the collective reasoning behind decisions that are made when a group designs an artifact. Generally such rationale involves consideration of various alternatives and why they were or weren’t chosen by the group. Typically this involves several people with differing views. Participatory design is thus an argumentative process, often with political overtones.

Clearly, since design involves deliberation and may also involve a healthy dose of politics, the process will work more effectively if it is structured. The structure should, however, be flexible: it must not constrain the choices and creativity of those involved. This is where the notation and practitioner (facilitator) come in: the notation lends structure to the discussion and the practitioner keeps it going in productive directions, yet in a way that sustains a coherent narrative. The latter is a creative process, much like an art. The representation (such as IBIS) – through its minimalist notation and grammar – helps keep the key issues, ideas and arguments firmly in focus. As Selvin noted in an earlier paper, this encourages collective creativity because it forces participants to think through their arguments more carefully than they would otherwise. Selvin coined the term knowledge art to refer to this process of developing and engaging with design representations. Indeed, the present paper is a detailed look at how practitioners create knowledge art – i.e. creative, expressive representations of the essence of design discussions. Quoting from the paper:

…we are looking at the experience of people in the role of caretakers or facilitators of such events – those who have some responsibility for the functioning of the group and session as a whole. Collaborative DR practitioners craft expressive representations on the fly with groups of people. They invite participant engagement, employing techniques like analysis, modeling, dialogue mapping, creative exploration, and rationale capture as appropriate. Practitioners inhabit this role and respond to discontinuities with a wide variety of styles and modes of action. Surfacing and describing this variety are our interests here.

The authors have significant experience in leading deliberations using IBIS and other design rationale methods. They propose a theoretical framework to identify and analyse various moves that practitioners make in order to keep the discussion moving in productive direction. They also describe various tools that they used to analyse discussions, and specific instances of the use of these tools. In the remainder of this post, I’ll focus on their theoretical framework rather than the specific case studies, as the former (I think) will be of more interest to readers. Further, I will focus on aspects of the framework that pertain to the practice – i.e. the things the practitioner does in order to keep the design representation coherent, the participants engaged and the discussion useful, i.e. moving in productive directions.

The dimensions of design rationale practice

So what do facilitators do when they lead deliberations? The key actions they undertake are best summed up in the authors’ words:

…when people act as PDR practitioners, they inherently make choices about how to proceed, give form to the visual and other representational products , help establish meanings, motives, and causality and respond when something breaks the expected flow of events , often having to invent fresh and creative responses on the spot.

This sentence summarises the important dimensions of the practice. Let’s look at each of the dimensions in brief:

- Ethics: At key points in the discussion, the practitioner is required to make decisions on how to proceed. These decisions cannot (should not!) be dispassionate or objective (as is often assumed), they need to be made with due consideration of “what is good and what is not good” from the perspective of the entire group.

- Aesthetics: This refers to the representation (map) of the discussion. As the authors put it, “All diagrammatic DR approaches have explicit and implicit rules about what constitutes a clear and expressive representation. People conversant with the approaches can quickly tell whether a particular artifact is a “good” example. This is the province of aesthetics.” In participatory design, representations are created as the discussion unfolds. The aesthetic responsibility of the practitioner is to create a map that is syntactically correct and expressive. Another aspect of the aesthetic dimension is that a “beautiful” map will engage the audience, much like a work of art.

- Narrative: One of the key responsibilities of the practitioner is to construct a coherent narrative from the diverse contributions made by the participants. Skilled practitioners pick up connections between different contributions and weave these into a coherent narrative. That said, the narrative isn’t just the practitioner’s interpretation; the practitioner has to ensure that everyone in the group is happy with the story; the story is to the group’ s story. A coherent narrative helps the group make sense of the discussion: specifically the issues canvassed, ideas offered and arguments for and against each of them. Building such a narrative can be challenging because design discussions often head off in unexpected directions.

- Sensemaking: During deliberations it is quite common that the group gets stuck. Progress can be blocked for a variety of reasons ranging from a lack of ideas on how to make progress to apparently irreconcilable differences of opinion on the best way to move forward. At these junctures the role of the practitioner is to break the impasse. Typically this involves conversational moves that open new ground (not considered by the group up to that point) or find ways around obstacles (perhaps by suggesting compromises or new choices). The key skill in sensemaking is the ability to improvise, which segues rather nicely into the next variable.

- Improvisation: Books such as Jeff Conklin’s classic on dialogue mapping describe some standard moves and good practices in PDR practice. In reality, however, a practitioner will inevitably encounter situations that cannot be tackled using standard techniques. In such situations the practitioner has to improvise. This could involve making unconventional moves within the representation or even using another representation altogether. These improvisations are limited only by the practitioner’s creativity and experience.

Using case studies, the authors illustrate how design rationale sessions can be analysed along the aforementioned dimensions, both at a micro and macro level. The former involves a detailed move-by-move study of the session and the latter an aggregated view, based on the overall tenor of episodes consisting of several moves. I won’t say any more about the analyses here, instead I’ll discuss the relevance of the model to the actual practice of design rationale techniques such as dialogue mapping.

Some reflections on the model

When I first heard about dialogue mapping, I felt the claims made about the technique were exaggerated: it seemed impossible that a simple notation like IBIS (which consists of just three elements and a simple grammar) could actually enhance collaboration and collective creativity of a group. With a bit of experience, I began to see that it actually did do what it claimed to do. However, I was unable to explain to others how or why it worked. In one conversation with a manager, I found myself offering hand-waving explanations about the technique – which he (quite rightly) found unconvincing. It seemed that the only way to see how or why it worked was to use it oneself. In short: I realised that the technique involved tacit rather than explicit knowledge.

Now, most practices– even the most mundane ones – involve a degree of tacitness. In fact, in an earlier post I have argued that the concept of best practice is flawed because it assumes that the knowledge involved in a practice can be extracted in its entirety and codified in a manner that others can understand and reproduce. This assumption is incorrect because the procedural aspects of a practice (which can be codified) do not capture everything – they miss aspects such as context and environmental influences, for instance. As a result a practice that works in a given situation may not work in another, even though the two may be similar. So it is with PDR techniques – they work only when tailored on the fly to the situation at hand. Context is king. In contrast the procedural aspects of PDR techniques– syntax, grammar etc – are trivial and can be learnt in a short time.

In my opinion, the value of the model is that it attempts to articulate tacit aspects of PDR techniques. In doing so, it tells us why the techniques work in one particular situation but not in another. How so? Well, the model tells us the things that PDR practitioners worry about when they facilitate PDR sessions – they worry about the form of the map (aesthetics), the story it tells (narrative), helping the group resolve difficult issues (sensemaking), making the right choices (ethics) and stepping outside the box if necessary (improvisation). These are tacit skills- they can’t be taught via textbooks, they can only be learnt by doing. Moreover, when such techniques fail the reason can usually be traced back to a failure (of the facilitator) along one or more of these dimensions.

Wrapping up

Techniques to capture participatory design rationale have been around for a while. Although it is generally acknowledged that such techniques aid the process of collaborative design, it is also known that their usefulness depends rather critically on the skill of the practitioner. This being the case, it is important to know what exactly skilled practitioners do that sets them apart from novices and journeymen. The model is a first step towards this. By identifying the dimensions of PDR practice, the model gives us a means to analyse practitioner moves during PDR sessions – for example, one can say that this was a sensemaking move or that was an improvisation. Awareness of these types of moves and how they work in real life situations can help novices learn the basics of the craft and practitioners master its finer points.