Archive for the ‘Issue Based Information System’ Category

Visualising content and context using issue maps – an example based on a discussion of Cox’s risk matrix theorem

Introduction

Some time ago I wrote a post on a paper by Tony Cox which describes some flaws in risk matrices (as they are commonly used) and proposes an axiomatic approach to address some of the problems. In a recent comment on that post, Tony Waisanen suggested that someone take up the challenge to map the content of the post and the ensuing discussion using issue mapping. Hence my motivation to write the present post.

My main aims in this post are to:

- Create an issue map visualising the content of my post on Cox’s paper.

- Incorporate points raised in the comments into the map, and show how they relate to Cox’s arguments.

A quick word about the notation and software before proceeding. I’ll use the IBIS (Issue-based information system) notation to map the argument. Those unfamiliar with IBIS will find a quick introduction here. The mapping is done using Compendium, an open source issue mapping tool (that can do other things too). I’ll provide a commentary as I build the map, because the detail behind the map cannot be seen in the screenshot

First map: the flaws in risk matrices and how to fix them

Cox ask’s the question: “What’s wrong with risk matrices?” – this is, in fact, the title of the paper in which he describes his theorem. The question is therefore an excellent starting point for our map.

As an answer to the question, Cox lists the following points as problems/flaws in risk matrices:

- Poor resolution: risk matrices use qualitative categories (typically denoted by colour – red, green, yellow). Risks within a category cannot be distiguished.

- Incorrect ranking of risks: In some cases, risks can end up in the wrong qualitative category – i.e. a quantitatively higher risk can be mistakenly categorised as a low risk and vice versa. In the worst case, this can lead to suboptimal resource allocation – i.e. a lower risk being given a higher priority.

- Subjective inputs: Often, the criteria used to rank risks are based on subjective inputs. Such subjective inputs are prone to cognitive bias. This leads to inaccurate and unreliable risk rankings.

See my posts limitations of scoring methods in risk analysis and cognitive biases as project meta-risks for more on the above points.

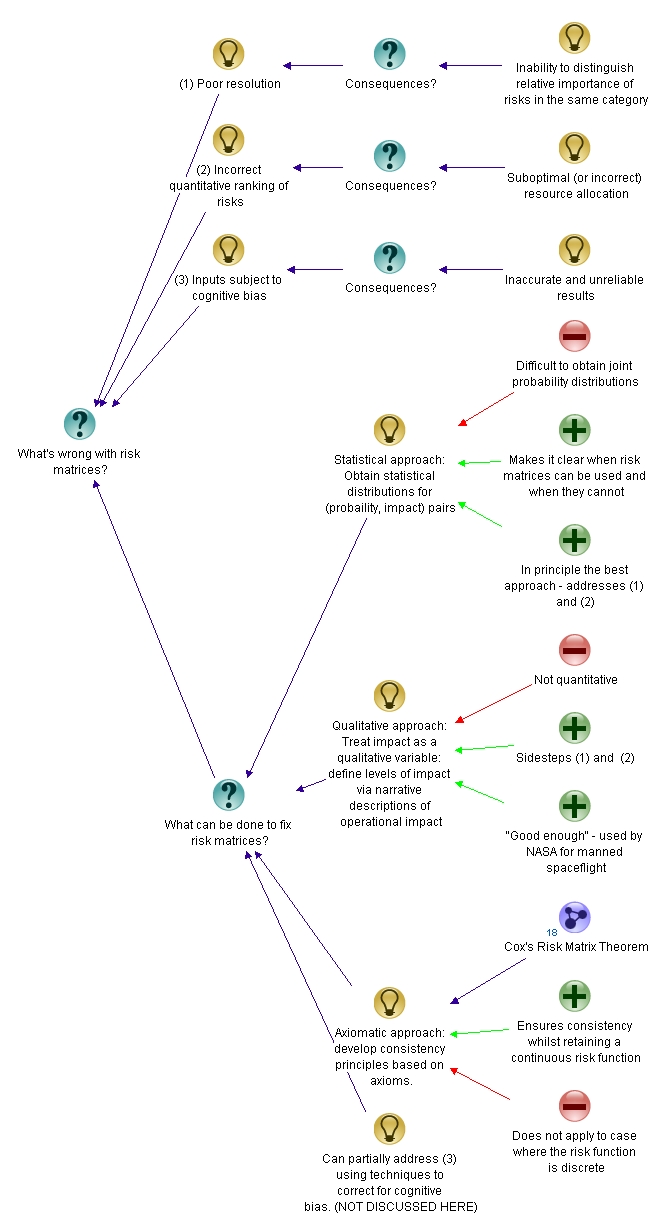

The map with the root question, problems (ideas or responses, in IBIS terminology) and their consequences is shown in Figure 1. Note that I’ve put numbers (1), (2) etc. against the points so that I can refer to them by number in other nodes.

The next question suggests itself: we’ve asked “What’s wrong with risk matrices?” so an obvious follow-up question is, “What can be done to fix risk matrices?” There are a few approaches available to address the problems. These are dicussed in my post and the discussion following it. The approaches can be summarised as follows:

- Statistical approach: This involves obtaining the correct statistical distributions for probability of the risk occuring and the impact of the risk. This is generally hard to do because of the lack of data. However, once this is done, it obviates the need for risk matrices. Furthermore, it warns us about situations in which risk matrices may mislead. In Cox’s words, “One (approach) is to consider applications in which there are sufficient data to draw some inferences about the statistical distribution of (Probability, Consequence) pairs. If data are sufficiently plentiful, then statistical and artificial intelligence tools … can potentially be applied to help design risk matrices that give efficient or optimal (according to various criteria) discrete approximations to the quantitative distribution of risks. In such data-rich settings, it might be possible to use risk matrices when they are useful (e.g., if probability and consequence are strongly positively correlated) and to avoid them when they are not (e.g., if probability and consequence are strongly negatively correlated).” This is, in principle, the best approach.

- Qualitative approach: This approach was discussed by Glen Alleman in this comment. It essentially involves characterising impact using qualitative information – i.e. narrative descriptions of impact. To quote from Glen’s comment, “...the numeric value of impacts are replaced by narrative descriptions of the actual operational impacts from the occurrence of the risk. These narratives are developed through analysis of the system…the quantitative risk as a product is abandoned in place of a classification of response to a predefined consequence.” This approach side steps a couple of the issues with risk matrices. Further, many risk aware organisations have used this method with great success (Glen mentions that NASA and the Department of Defense use such an approach to analyse risks on spaceflight/aviation projects)

- Axiomatic approach: This is the approach that Tony Cox discusses in his paper. It has the advantage of being simple – it assumes that the risk function (defined as probability x impact, for example) is continuous whilst also ensuring consistency to the extent possible (i.e. ensuring a correct quantitative ranking of risks). The downside, as Glen emphasises in his comments, is that risk functions are actually discrete, as discussed in (1) above. Cox’s arguments hinge on the continuity of the risk function, so they do not apply to the discrete case.

The map with these approaches added in is depicted in Figure 2. Note that I’ve added Cox’s theorem in as a map node, indicating that a detailed discussion of the theorem is presented in a separate map.

Note also, that I have added an idea node representing how the issue regarding subjective inputs can be addressed. I will not pursue this point further in the present post as it did not come up in the discussion. That said, I have discussed this point in some detail in an article on cognitive bias in project risk management.

Second map: Cox’s risk matrix theorem

Since the entire discussion is based on Cox’s arguments, it is worth looking into his paper in some detail – in particular, at the axioms and the theorem itself. It is convenient to hive this material off into a separate map, but one connected to the original map (see the map node representing the theorem in Figure 2 above).

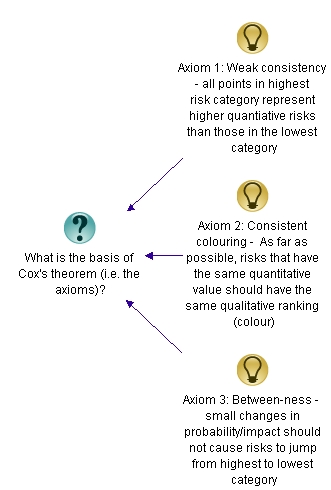

The root question of the new map would be, “What is the basis of Cox’s theorem?” Answer: the theorem is based on the axioms and other (tacit) assumptions.

Now, my earlier post on Cox’s theorem contains a very detailed treatment of the axioms, so I’ll offer only a one-line explanation for each here. The axioms are:

- Weak consistency – which states that all risks in the highest category (red) must represent quantitatively higher risks than those in the lowest category (green).

- Consistent colouring – As far as possible, risks with the same quantitative value must have the same colour.

- Between-ness – small changes in probability or impact (i.e. the risk function) should not cause a risk to move from the highest (red) to lowest (green) or vice versa.

The axioms are intuitively appealing – they express a basic consistency that one would expect risk matrices to satisfy. The secondary map, with the three axioms shown is depicted in Figure 3.

Cox’s theorem, which essentially follows from these axioms, can be stated as follows: In a risk matrix that satisfies the three axioms, all cells in the bottom row and left-most column must be green and all cells in the second from bottom row and second from left column must be non-red.

The theorem has two corollaries:

- 2×2 matrices cannot satisfy the theorem.

- 3×3 and 4×4 matrices which satisfy the theorem have a unique colouring scheme.

These are rather surprising conclusions, arrived at from some very intuitive axioms. The secondary map, with the theorem and corollaries added in is shown in Fig. 4.

That completes the map of the theorem. However, in this comment Glen Alleman pointed out that the assumption of a continuous function to describe risk (such as risk = probability x impact, where both quantities on the right hand side are continuous functions) is questionable. He also makes the point the probability is specified by a distribution, and numerical values that come out of distributions cannot be combined via arithmetic operations. The reason that folks make the simplifying assumptions (of continutity and ignoring the probabilistic nature of the variables) is that it is intuitive and easy to work with. As I mentioned in one of my responses to the comments, one can choose to define risk this way although it isn’t logically sound. Cox’s theorem essentially specifies consistency conditions that need to be satisfied when such ad-hoc approaches are used. The map with this discussion included is shown in Figure 5 (click anywhere on figure to view a full-sized image)

That completes the mapping exercise: Figures 2 and 5 represent a fairly complete map of the post and the discussion around it.

Caveats and conclusions

At the risk of belaboring the obvious, the maps represent my interpretation of Cox’s work and my interpretation of others’ comments on my post on Cox’s work. Further, the discussion on which the maps are based is far from comprehensive because it did not cover other limitations of risk matrices. Please see my post on limitations of scoring methods in risk analysis for a detailed discussion of these.

Before closing, it is worth looking at the Figures 2 and 5 from a broader perspective: the figures make clear the context of the discussion in a way that is simply not possible through words. As an example, Figure 2 lays bare the context of Cox’s theorem – it emphasises, for example, that Cox’s approach isn’t the only method to fix what’s wrong with risk matrices. Further, Figure 5 distinguishes between explicitly declared and tacit assumptions. Examples of the former are the three axioms and that of the latter is the assumption of continuity.

In this post I’ve summarised the content and context of Cox’s risk matrix theorem via issue mapping. The maps provide an “at a glance” summary of the theorem alongwith supporting assumptions and axioms. Further, the maps also incorporate key elements of readers’ reaction regarding the post. I hope this example clarifies the content and context of my earlier post on Cox’s risk matrix theorem, whilst also serving as a demonstration of the utility of the IBIS notation in mapping complex arguments.

Acknowledgements:

Thanks go out to Tony Waisanen for suggesting that the post and comments be issue mapped, and to Glen Alleman, Robert Higgins and Prakash Vaidhyanathan for their contributions to the discussion.

The Approach: a dialogue mapping story

Jack could see that the discussion was going nowhere: the group been talking about the pros and cons of competing approaches for over half an hour, but they kept going around in circles. As he mulled over this, Jack got an idea – he’d been playing around with a visual notation called IBIS (Issue-Based Information System) for a while, and was looking for an opportunity to use it to map out a discussion in real time (Editor’s note: readers unfamiliar with IBIS may want to have a look at this post and this one before proceeding). “Why not give it a try,” he thought, “I can’t do any worse than this lot.” Decision made, he waited for a break in the conversation and dived in when he got one…

“I have a suggestion,” he said. “There’s this conversation mapping tool that I’ve been exploring for a while. I believe it might help us reach a common understanding of the approaches we’ve been discussing. It may even help facilitate a decision. Do you mind if I try it?”

“Pfft – I’m all for it if it helps us get to a decision.” said Max. He’d clearly had enough too.

Jack looked around the table. Mary looked puzzled, but nodded her assent. Rick seemed unenthusiastic, but didn’t voice any objections. Andrew – the boss – had a here-he-goes-again look on his face (Jack had a track record of “ideas”) but, to Jack’s surprise, said, “OK. Why not? Go for it.”

“Give me a minute to get set up,” said Jack. He hooked his computer to the data projector. Within a couple of minutes, he had a blank IBIS map displayed on-screen. This done, he glanced up at the others: they were looking at screen with expressions ranging from curiosity (Mary) to skepticism (Max).

“Just a few words about what I’m going to do, he said. “I’ll be using a notation called IBIS – or issue based information system – to capture our discussion. IBIS has three elements: issues, ideas and arguments. I’ll explain these as we go along. OK – Let’s get started with figuring out what we want out of the discussion. What’s our aim?” he asked.

His starting spiel done, Jack glanced at his colleagues: Max seemed a tad more skeptical than before; Rick ever more bored; Andrew and Mary stared at the screen. No one said anything.

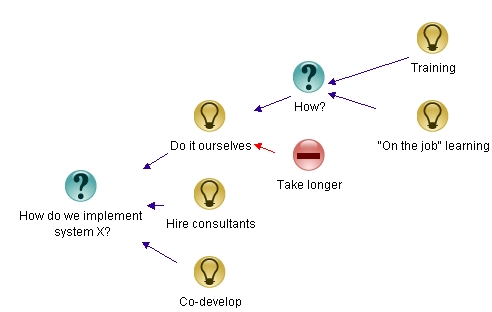

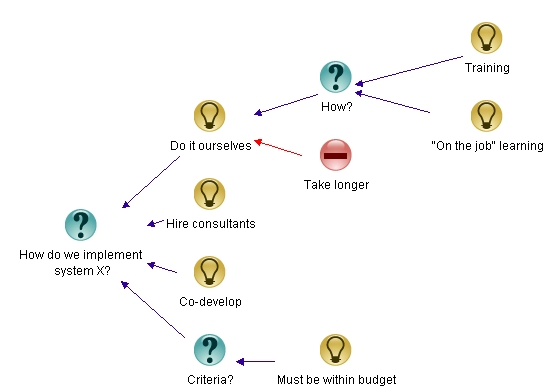

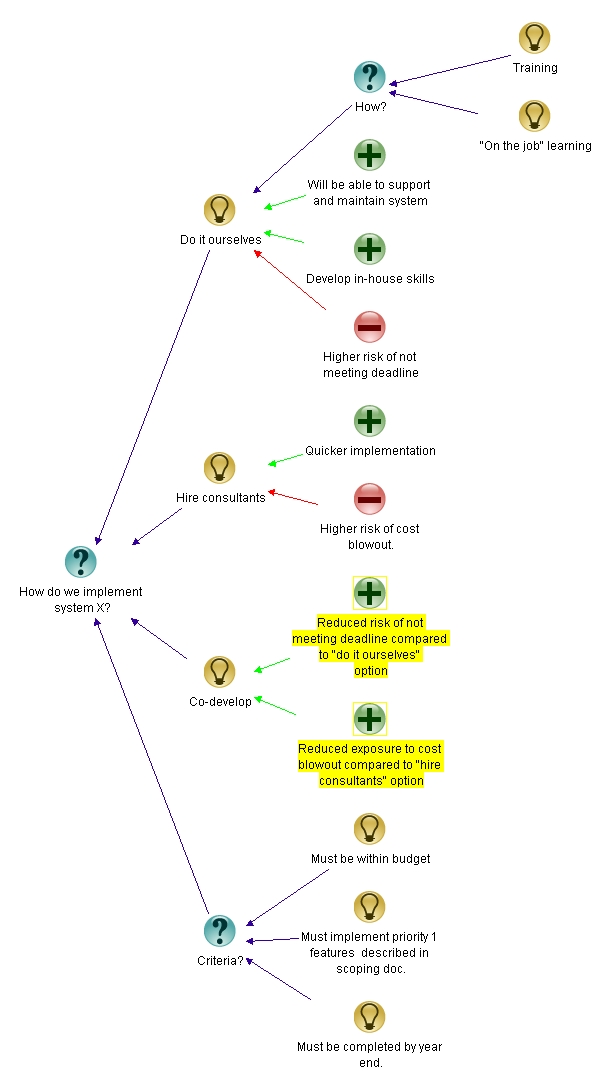

Just as he was about to prompt them by asking another question, Mary said, “I’d say it’s to explore options for implementing the new system and find the most suitable one. Phrased as a question: How do we implement system X?”

Jack glanced at the others. They all seemed to agree – or at least, didn’t disagree – with Mary, “Excellent,” he said, “I think that’s a very good summary of what we’re trying to do.” He drew a question node on the map and continued: “Most discussions of this kind are aimed at resolving issues or questions. Our root question is: What are our options for implementing system X, or as Mary put it, How do we implement System X.”

“So, what’s next,” asked Max. He still looked skeptical, but Jack could see that he was intrigued. Not bad, he thought to himself….

“Well, the next step is to explore ideas that address or resolve the issue. So, ideas should be responses to the question: how should we implement system X? Any suggestions?”

“We’d have to engage consultants,” said Max. “We don’t have in-house skills to implement it ourselves.”

Jack created an idea node on the map and began typing. “OK – so we hire consultants,” he said. He looked up at the others and continued, “In IBIS, ideas are depicted by light bulbs. Since ideas respond to questions, I draw an arrow from the idea to the root question, like so:

“I think doing it ourselves is an option,” said Mary, “We’d need training and it might take us longer because we’d be learning on the job, but it is a viable option. ”

“Good,” said Jack, “You’ve given us another option and some ways in which we might go about implementing the option. Ideally, each node should represent a single – or atomic – point. So I’ll capture what you’ve said like so.” He typed as fast he could, drawing nodes and filling in detail.

As he wrote he said, “Mary said we could do it ourselves – that’s clearly a new idea – an implementation option. She also partly described how we might go about it: through training to learn the technology and by learning on the job. I’ve added in “How” as a question and the two points that describe how we’d do it as ideas responding to the question.” He paused and looked around to check that every one was with him, then continued. “But there’s more: she also mentioned a shortcoming of doing it ourselves – it will take longer. I capture this as an argument against the idea; a con, depicted as red minus in the map.”

He paused briefly to look at his handiwork on-screen, then asked, “Any questions?”

Rick asked, “Are there any rules governing how nodes are connected?”

“Good question! In a nutshell: ideas respond to questions and arguments respond to ideas. Issues, on the other hand, can be generated from any type of node. I can give you some links to references on the Web if you’re interested.”

“That might be useful for everyone,” said Andrew. “Send it out to all of us.”

“Sure. Let’s move on. So, does anyone have any other options?”

“Umm..not sure how it would work, but what about co-development?” Suggested Rick.

“Do you mean collaborative development with external resources?” asked Jack as he began typing.

“Yes,” confirmed Rick.

“What about costs? We have a limited budget for this,” said Mary.

“Good point,” said Jack as he started typing. “This is a constraint that must be satisfied by all potential approaches.” He stopped typing and looked up at the others, “This is important: criteria apply to all potential approaches, so the criterial question should hang off the root node,” he said. “Does this make sense to everyone?”

“I’m not sure I understand,” said Andrew. “Why are the criteria separate from the approaches?”

“They aren’t separate. They’re a level higher than any specific approach because they apply to all solutions. Put another way, they relate to the root issue – How do we implement system X – rather than a specific solution.”

“Ah, that makes sense,” said Andrew. “This notation seems pretty powerful.”

“It is, and I’ll be happy to show you some more features later, but let’s continue the discussion for now. Are there any other criteria?”

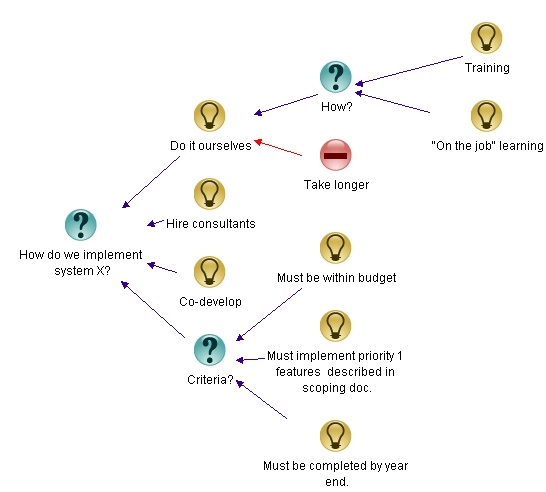

“Well, we must have all the priority 1 features described in the scoping document implemented by the end of the year,” said Andrew. One can always count on the manager to emphasise constraints.

“OK, that’s two criteria actually: must implement priority 1 features and must implement by year end,” said Jack, as he added in the new nodes. “No surprises here,” he continued, “we have the three classic project constraints – budget, scope and time.”

The others were now engaged with the map, looking at it, making notes etc. Jack wanted to avoid driving the discussion, so instead of suggesting how to move things forward, he asked, “What should we consider next?”

“I can’t think of any other approaches,” said Mary. Does anyone have suggestions, or should we look at the pros and cons of the listed approaches?”

“I’ve said it before; I’ll say it again: I think doing it ourselves is a dum..,.sorry, not a good idea. It is fraught with too much risk…” started Max.

“No it isn’t,” countered Mary, “on the contrary, hiring externals is more risky because costs can blowout by much more than if we did it ourselves.”

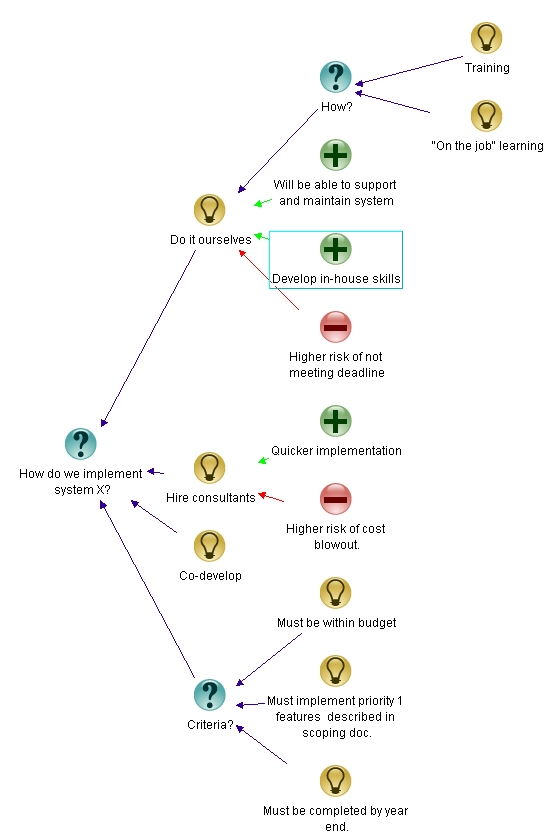

“Good points,” said Jack, as he noted Mary’s point. “Max, do you have any specific risks in mind?”

“Time – it can take much longer,” said Max.

“We’ve already captured that as a con of the do-it-ourselves approach,” said Jack.

“Hmm…that’s true, but I would reword it to state that we have a hard deadline. Perhaps we could say – may not finish in allotted time – or something similar.”

“That’s a very good point,” said Jack, as he changed the node to read: higher risk of not meeting deadline. The map was coming along nicely now, and had the full attention of folks in the room.

“Alright,” he continued, “so are there any other cons? If not, what about pros – arguments in support of approaches?”

“That’s easy, “ said Mary, “doing it ourselves will improve our knowledge of the technology; we’ll be able to support and maintain the system ourselves.”

“Doing it through consultants will enable us to complete the project quicker,” countered Max.

Jack added in the pros and paused, giving the group some time to reflect on the map.

Rick and Mary, who were sitting next to each other, had a whispered side-conversation going; Andrew and Max were writing something down. Jack waited.

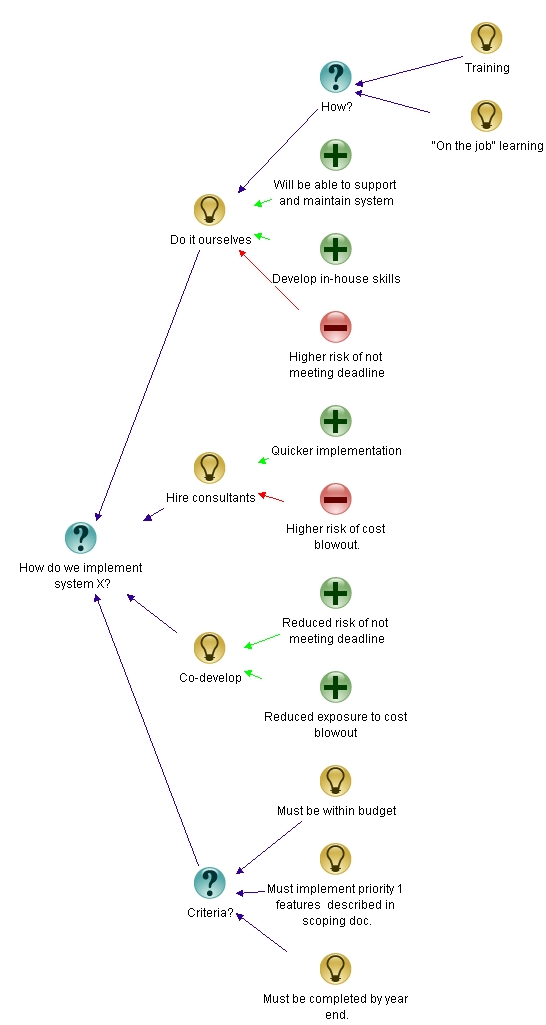

“Mary and I have an idea,” said Rick. “We could take an approach that combines the best of both worlds – external consultants and internal resources. Actually, we’ve already got it down as a separate approach – co-development, but we haven’t discussed it yet..” He had the group’s attention now. “Co-development allows us to use consultants’ expertise where we really need it and develop our own skills too. Yes, we’d need to put some thought into how it would work, but I think we could do it.”

“I can’t see how co-development will reduce the time risk – it will take longer than doing it through consultants.” said Max.

“True,” said Mary, “but it is better than doing it ourselves and, more important, it enables us to develop in-house skills that are needed to support and maintain the application. In the long run, this can add up to a huge saving. Just last week I read that maintenance can be anywhere between 60 to 80 percent of total system costs.”

“So you’re saying that it reduces implementation time and results in a smaller exposure to cost blowout?” asked Jack.

“Yes,” said Mary

Jack added in the pros and waited.

“I still don’t see how it reduces time,” said Max.

“It does, when compared to the option of doing it ourselves,” retorted Mary.

“Wait a second guys,” said Jack. “What if I reword the pros to read – Reduced implementation time compared to in-house option and Reduced cost compared to external option.”

He looked at Mary and Max. – both seemed to OK with this, so he typed in the changes.

Jack asked, “So, are there any other issues, ideas or arguments that anyone would like to add?”

“From what’s on the map, it seems that co-development is the best option,” said Andrew. He looked around to see what the others thought: Rick and Mary were nodding; Max still looked doubtful.

Max asked, “how are we going to figure out who does what? It isn’t easy to partition work cleanly when teams have different levels of expertise.”

Jack typed this in as a con.

“Good point,” said Andrew. “There may be ways to address this concern. Do you think it would help if we brought some consultants in on a day-long engagement to workshop a co-development approach with the team? ”

Max nodded, “Yeah, that might work,” he said. “It’s worth a try anyway. I have my reservations, but co-development seems the best of the three approaches.”

“Great,“ said Andrew, “I’ll get some consultants in next week to help us workshop an approach.”

Jack typed in this exchange, as the others started to gather their things. “Anything else to add?” he asked.

Everyone looked up at the map. “No, that’s it, I think,” said Mary.

“Looks good,” said Mike . “Be sure to send us a copy of the map.”

“Sure, I’ll print copies out right away,” said Jack. “Since we’ve developed it together, there shouldn’t be any points of disagreement.”

“That’s true,” said Andrew, “another good reason to use this tool.” Gathering his papers, he asked, “Is there anything else? He looked around the table. “ Alright then, I’ll see you guys later, I’m off to get some lunch before my next meeting.”

Jack looked around the group. Helped along by IBIS and his facilitation, they’d overcome their differences and reached a collective decision. He had thought it wouldn’t work, but it had.

“ Jack, thanks for your help with the discussion. IBIS seems to be a great way to capture discussions. Don’t forget to send us those references,” said Mary, gathering her notes.

“I’ll do that right away,” said Jack, “and I’ll also send you some information about Compendium – the open-source software tool I used to create the map.”

“Great,” said Mary. “I’ve got to run. See you later.”

“See you later,” replied Jack.

————

Further Reading:

1. Jeff Conklin’s book is a must-read for any one interested in dialogue mapping. I’ve reviewed it here.

2. For more on Compendium, see the Compendium Institute site.

3. See Paul Culmsee’s series of articles, The One Best Practice to Rule Them All, for an excellent and very entertaining introduction to issue mapping.

4. See this post and this one for examples of how IBIS can be used to visualise written arguments.

5. See this article for a dialogue mapping story by Jeff Conklin.

IBIS, dialogue mapping, and the art of collaborative knowledge creation

Introduction

In earlier posts I’ve described a notation called IBIS (Issue-based information system), and demonstrated its utility in visualising reasoning and resolving complex issues through dialogue mapping. The IBIS notation consists of just three elements (issues, ideas and arguments) that can be connected in a small number of ways. Yet, despite these limitations, IBIS has been found to enhance creativity when used in collaborative design discussions. Given the simplicity of the notation and grammar, this claim is surprising, even paradoxical. The present post resolves this paradox by viewing collaborative knowledge creation as an art, and considers the aesthetic competencies required to facilitate this art.

Knowledge art

In a position paper entitled, The paradox of the “practice level” in collaborative design rationale, Al Selvin draws an analogy between design discussions using Compendium (an open source IBIS-based argument mapping tool) and art. He uses the example of the artist Piet Mondrian, highlighting the difference in style between Mondrian’s earlier and later work. To quote from the paper,

Whenever I think of surfacing design rationale as an intentional activity — something that people engaged in some effort decide to do (or have to do), I think of Piet Mondrian’s approach to painting in his later years. During this time, he departed from the naturalistic and impressionist (and more derivative, less original) work of his youth (view an image here) and produced the highly abstract geometric paintings (view an image here) most associated with his name…

Selvin points out that the difference between the first and the second paintings is essentially one of abstraction: the first one is almost instantly recognisable as a depiction of dunes on a beach whereas the second one, from Mondrian’s minimalist period, needs some effort to understand and appreciate, as it uses a very small number of elements to create a specific ambience. To quote from the paper again,

“One might think (as many in his day did) that he was betraying beauty, nature, and emotion by going in such an abstract direction. But for Mondrian it was the opposite. Each of his paintings in this vein was a fresh attempt to go as far as he could in the depiction of cosmic tensions and balances. Each mattered to him in a deeply personal way. Each was a unique foray into a depth of expression where nothing was given and everything had to be struggled for to bring into being without collapsing into imbalance and irrelevance. The depictions and the act of depicting were inseparable. We get to look at the seemingly effortless result, but there are storms behind the polished surfaces. Bringing about these perfected abstractions required emotion, expression, struggle, inspiration, failure and recovery — in short, creativity…”

In analogy, Selvin contends that a group of people who work through design issues using a minimalist notation such as IBIS can generate creative new ideas. In other words: IBIS, when used in a group setting such as dialogue mapping, can become a vehicle for collaborative creativity. The effectiveness of the tool, though, depends on those who wield it:

“…To my mind using tools and methods with groups is a matter of how effective, artistic, creative, etc. whoever is applying and organizing the approach can be with the situation, constraints, and people. Done effectively, even the force-fitting of rationale surfacing into a “free-flowing” design discussion can unleash creativity and imagination in the people engaged in the effort, getting people to “think different” and look at their situation through a different set of lenses. Done ineffectively, it can impede or smother creativity as so many normal methods, interventions, and attitudes do…”

Although Selvin’s discussion is framed in the context of design discussions using Compendium, this is but dialogue mapping by another name. So, in essence, he makes a case for viewing the collaborative generation of knowledge (through dialogue mapping or any other means) as an art. In fact, in another article, Selvin uses the term knowledge art to describe both the process and the product of creating knowledge as discussed above. Knowledge Art as he sees it, is a marriage of the two forms of discourse that make up the term. On the one hand, we have knowledge which, “… in an organizational setting, can be thought of as what is needed to perform work; the tacit and explicit concepts, relationships, and rules that allow us to know how to do what we do.” On the other, we have art which “… is concerned with heightened expression, metaphor, crafting, emotion, nuance, creativity, meaning, purpose, beauty, rhythm, timbre, tone, immediacy, and connection.”

Facilitating collaborative knowledge creation

In the business world, there’s never enough time to deliberate or think through ideas (either individually or collectively): everything is done in a hurry and the result is never as good as it should or could be; the picture never quite complete. However, as Selvin says,

“…each moment (spent discussing or thinking through ideas or designs) can yield a bit of the picture, if there is a way to capture the bits and relate them, piece them together over time. That capturing and piecing is the domain of Knowledge Art. Knowledge Art requires a spectrum of skills, regardless of how it’ practiced or what form it takes. It means listening and paying attention, determining the style and level of intervention, authenticity, engagement, providing conceptual frameworks and structures, improvisation, representational skill and fluidity, and skill in working with electronic information…”

So, knowledge art requires a wide range of technical and non-technical skills. In previous posts I’ve discussed some of technical skills required – fluency with IBIS, for example. Let’s now look at some of the non-technical competencies.

What are the competencies needed for collaborative knowledge creation? Palus and Horth offer some suggestions in their paper entitled, Leading Complexity; The Art of Making Sense. They define the concept of creative leadership as making shared sense out of complexity and chaos and the crafting of meaningful action. Creative leadership is akin to dialogue mapping, which Jeff Conklin describes as a means to achieve a shared understanding of wicked problems and a shared commitment to solving them. The connection between creative leadership and dialogue mapping is apparent once one notices the similarity between their definitions. So the competencies of creative leadership should apply to dialogue mapping (or collaborative knowledge creation) as well.

Palus and Horth describe six basic competencies of creative leadership. I outline these below, mentioning their relevance to dialogue mapping:

Paying Attention: This refers to the ability to slow down discourse with the aim of achieving a deep understanding of the issues at hand. A skilled dialogue mapper has to be able to listen; to pay attention to what’s being said.

Personalizing: This refers to the ability to draw upon personal experiences, interests and passions whilst engaged in work. Although the connection to dialogue mapping isn’t immediately evident, the point Palus and Horth make is that the ability to make connections between work and one’s interests and passions helps increase involvement, enthusiasm and motivation in tackling work challenges.

Imaging: This refers to the ability to visualise problems so as to understand them better, using metaphors, pictures stories etc to stimulate imagination, intuition and understanding. The connection to dialogue mapping is clear and needs no elaboration.

Serious play: This refers to the ability to experiment with new ideas; to learn by trying and doing in a non-threatening environment. This is something that software developers do when learning new technologies. A group engaged in a dialogue mapping must have a sense of play; of trying out new ideas, even if they seem somewhat unusual.

Collaborative enquiry: This refers to the ability to sustain productive dialogue in a diverse group of stakeholders. Again, the connection to dialogue mapping is evident.

Crafting: This refers to the ability to synthesise issues, ideas, arguments and actions into coherent, meaningful wholes. Yet again, the connection to dialogue mapping is clear – the end product is ideally a shared understanding of the problem and a shared commitment to a meaningful solution.

Palus and Horth suggest that these competencies have been ignored in the business world because:

- They are seen as threatening the status quo (creativity is to feared because it invariably leads to changes).

- These competencies are aesthetic, and the current emphasis on scientific management devalues competencies that are not rational or analytical.

The irony is that creative scientists have these aesthetic competencies (or qualities) in spades. At the most fundamental level science is an art – it is about constructing theories or designing experiments that make sense of the world. Where do the ideas for these new theories or experiments come from? Well, they certainly aren’t out there in the objective world; they come from the imagination of the scientist. Science, in the real sense of the word, is knowledge art. If these competencies are useful in science, they should be more than good enough for the business world.

Summing up

To sum up: knowledge creation in an organisational context is best viewed as an art – a collaborative art. Visual representations such as IBIS provide a medium to capture snippets of knowledge and relate them, or piece them together over time. They provide the canvas, brush and paint to express knowledge as art through the process of dialogue mapping.