Archive for the ‘Issue Based Information System’ Category

The what and whence of issue-based information systems

Over the last few months I’ve written a number of posts on IBIS (short for Issue Based Information System), an argument visualisation technique invented in the early 1970s by Horst Rittel and Werner Kunz. IBIS is best known for its use in dialogue mapping – a collaborative approach to tackling wicked problems – but it has a range of other applications as well (capturing project knowledge is a good example). All my prior posts on IBIS focused on its use in specific applications. Hence the present piece, in which I discuss the “what” and “whence” of IBIS: its practical aspects – notation, grammar etc. – along with its origins, advantages and limitations

I’ll begin with a brief introduction to the technique (in its present form) and then move on to its origins and other aspects.

A brief introduction to IBIS

IBIS consists of three main elements:

- Issues (or questions): these are issues that need to be addressed.

- Positions (or ideas): these are responses to questions. Typically the set of ideas that respond to an issue represents the spectrum of perspectives on the issue.

- Arguments: these can be Pros (arguments supporting) or Cons (arguments against) an issue. The complete set of arguments that respond to an idea represents the multiplicity of viewpoints on it.

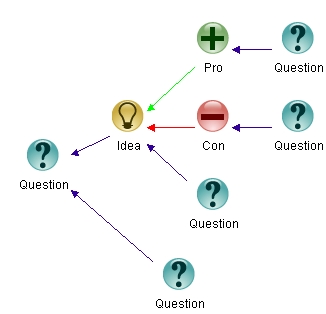

The best IBIS mapping tool is Compendium – it can be downloaded here. In Compendium, the IBIS elements described above are represented as nodes as shown in Figure 1: issues are represented by green question nodes; positions by yellow light bulbs; pros by green + signs and cons by red – signs. Compendium supports a few other node types, but these are not part of the core IBIS notation. Nodes can be linked only in ways specified by the IBIS grammar as I discuss next.

Figure 1: IBIS Elements

The IBIS grammar can be summarized in a few simple rules:

- Issues can be raised anew or can arise from other issues, positions or arguments. In other words, any IBIS element can be questioned. In Compendium notation: a question node can connect to any other IBIS node.

- Ideas can only respond to questions – i.e. in Compendium “light bulb” nodes can only link to question nodes. The arrow pointing from the idea to the question depicts the “responds to” relationship.

- Arguments can only be associated with ideas – i.e in Compendium + and – nodes can only link to “light bulb” nodes (with arrows pointing to the latter)

The legal links are summarized in Figure 2 below.

The rules are best illustrated by example- follow the links below to see some illustrations of IBIS in action:

- See this post for a simple example of dialogue mapping.

- See this post or this one for examples of argument visualisation .

- See this post for the use IBIS in capturing project knowledge.

Now that we know how IBIS works and have seen a few examples of it in action, it’s time to trace its history from its origins to the present day.

Wicked origins

A good place to start is where it all started. IBIS was first described in a paper entitled, Issues as elements of Information Systems; written by Horst Rittel (who coined the term “wicked problem”) and Werner Kunz in July 1970. They state the intent behind IBIS in the very first line of the abstract of their paper:

Issue-Based Information Systems (IBIS) are meant to support coordination and planning of political decision processes. IBIS guides the identification, structuring, and settling of issues raised by problem-solving groups, and provides information pertinent to the discourse.

Rittel’s preoccupation was the area of public policy and planning – which is also the context in which he defined wicked problems originally. He defined the term in his landmark paper of 1973 entitled, Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning. A footnote to the paper states that it is based on an article that he presented at an AAAS meeting in 1969. So it is clear that he had already formulated his ideas on wickedness when he wrote his paper on IBIS in 1970.

Given the above background it is no surprise that Rittel and Kunz foresaw IBIS to be the:

…type of information system meant to support the work of cooperatives like governmental or administrative agencies or committees, planning groups, etc., that are confronted with a problem complex in order to arrive at a plan for decision…

The problems tackled by such cooperatives are paradigm-defining examples of wicked problems. From the start, then, IBIS was intended as a tool to facilitate a collaborative approach to solving such problems.

Operation of early systems

When Rittel and Kunz wrote their paper, there were three IBIS-type systems in operation: two in governmental agencies (in the US, one presumes) and one in a university environment (possibly, Berkeley, where Rittel worked). Although it seems quaint and old-fashioned now, it is no surprise that they were all manual, paper-based systems- the effort and expense involved in computerizing such systems in the early 70s would have been prohibitive, and the pay-off questionable.

The paper also offers a short description of how these early IBIS systems operated:

An initially unstructured problem area or topic denotes the task named by a “trigger phrase” (“Urban Renewal in Baltimore,” “The War,” “Tax Reform”). About this topic and its subtopics a discourse develops. Issues are brought up and disputed because different positions (Rittel’s word for ideas or responses) are assumed. Arguments are constructed in defense of or against the different positions until the issue is settled by convincing the opponents or decided by a formal decision procedure. Frequently questions of fact are directed to experts or fed into a documentation system. Answers obtained can be questioned and turned into issues. Through this counterplay of questioning and arguing, the participants form and exert their judgments incessantly, developing more structured pictures of the problem and its solutions. It is not possible to separate “understanding the problem” as a phase from “information” or “solution” since every formulation of the problem is also a statement about a potential solution.

Even today, forty years later, this is an excellent description of how IBIS is used to facilitate a common understanding of complex (or wicked) problems. The paper contains an overview of the structure and operation of manual IBIS-type systems. However, I’ll omit these because they are of little relevance in the present-day world.

As an aside, there’s a term that’s conspicuous by its absence in the Rittel-Kunz paper: design rationale. Rittel must have been aware of the utility of IBIS in capturing design rationale: he was a professor of design science at Berkley and design reasoning was one of his main interests. So it is somewhat odd that he does not mention this term even once in his IBIS paper.

Fast forward a couple decades (and more!)

In a paper published in 1988 entitled, gIBIS: A hypertext tool for exploratory policy discussion, Conklin and Begeman describe a prototype of a graphical, hypertext-based IBIS-type system (called gIBIS) and its use in capturing design rationale (yes, despite the title of the paper, it is more about capturing design rationale than policy discussions). The development of gIBIS represents a key step between the original Rittel-Kunz version of IBIS and its present-day version as implemented in Compendium. Amongst other things, IBIS was finally off paper and on to disk, opening up a new world of possibilities.

gIBIS aimed to offer users:

- The ability to capture design rationale – the options discussed (including the ones rejected) and the discussion around the pros and cons of each.

- A platform for promoting computer-mediated collaborative design work – ideally in situations where participants were located at sites remote from each other.

- The ability to store a large amount of information and to be able to navigate through it in an intuitive way.

Before moving on, one point needs to be emphasized: gIBIS was intended to be used in collaborative settings; to help groups achieve a shared understanding of central issues, by mapping out dialogues in real time. In present-day terms – one could say that it was intended as a tool for sense making.

The gIBIS prototype proved successful enough to catalyse the development of Questmap, a commercially available software tool that supported IBIS. However, although there were some notable early successes in the real-time use of IBIS in industry environments (see this paper, for example), these were not accompanied by widespread adoption of the technique. Other graphical, IBIS-like methods to capture design rationale were proposed (an example is Questions, Options and Criteria (QOC) proposed by MacLean et. al. in 1991), but these too met with a general reluctance in adoption.

Making sense through IBIS

The reasons for the lack of traction of IBIS-type techniques in industry are discussed in an excellent paper by Shum et. al. entitled, Hypermedia Support for Argumentation-Based Rationale: 15 Years on from gIBIS and QOC. The reasons they give are:

- For acceptance, any system must offer immediate value to the person who is using it. Quoting from the paper, “No designer can be expected to altruistically enter quality design rationale solely for the possible benefit of a possibly unknown person at an unknown point in the future for an unknown task. There must be immediate value.” Such immediate value is not obvious to novice users of IBIS-type systems.

- There is some effort involved in gaining fluency in the use of IBIS-based software tools. It is only after this that users can gain an appreciation of the value of such tools in overcoming the limitations of mapping design arguments on paper, whiteboards etc.

The intellectual effort – or cognitive overhead, as it is called in academese – in using IBIS in real time involves:

- Teasing out issues, ideas and arguments from the dialogue.

- Classifying points raised into issues, ideas and arguments.

- Naming (or describing) the point succinctly.

- Relating (or linking) the point to an existing node.

This is a fair bit of work, so it is no surprise that beginners might find it hard to use IBIS to map dialogues. However, once learnt, a skilled practitioner can add value to design (and more generally, sense making) discussions in several ways including:

- Keeping the map (and discussion) coherent and focused on pertinent issues.

- Ensuring that all participants are engaged in contributing to the map (and hence the discussion).

- Facilitating useful maps (and dialogues) – usefulness being measured by the extent to which the objectives of the session are achieved.

See this paper by Selvin and Shum for more on these criteria. Incidentally, these criteria are a qualitative measure of how well a group achieves a shared understanding of the problem under discussion. Clearly, there is a good deal of effort involved in learning and becoming proficient at using IBIS-type systems, but the payoff is an ability to facilitate a shared understanding of wicked problems – whether in public planning or in technical design.

Why IBIS is better than conventional modes of documentation

IBIS has several advantages over conventional documentation systems. Rittel and Kunz’s 1970 paper contains a nice summary of the advantages, which I paraphrase below:

- IBIS can bridge the gap between discussions and records of discussions (minutes, audio/video transcriptions etc,). IBIS sits between the two, acting as a short term memory. The paper thus foreshadows the use of issue-based systems as an aid to organizational or project memory.

- Many elements (issue, ideas or arguments) that come up in a discussion have contextual meanings that are different from any pre-existing definitions. In discussions, contextual meaning is more than formal meaning. IBIS captures the former in a very clear way – for example a response to a question “What do we mean by X? elicits the meaning of X in the context of the discussion, which is then subsequently captured as an idea (position)”.

- Related to the above, the commonality of an issue with other, similar issues might be more important than its precise meaning. To quote from the paper, “…the description of the subject matter in terms of librarians or documentalists (sic) may be less significant than the similarity of an issue with issues dealt with previously and the information used in their treatment…” With search technologies available, this is less of an issue now. However, search technologies are still limited in terms of finding matches between “similar” items (How is “similar” defined? Ans: it depends on context). A properly structured, context-searchable IBIS-based project archive may still be more useful than a conventional document archive based on a document management system.

- The reasoning used in discussions is made transparent, as is the supporting (or opposing) evidence. (see my post on visualizing argumentation for example)

- The state of the argument (discussion) at any time can be inferred at a glance (unlike the case in written records). See this post for more on the advantages of visual documentation over prose.

Issues with issue-based information systems

Lest I leave readers with the impression that IBIS is a panacea, I should emphasise that it isn’t. According to Conklin, IBIS maps have the following limitations:

- They atomize streams of thought into unnaturally small chunks of information thereby breaking up any smooth rhetorical flow that creates larger, more meaningful chunks of narrative.

- They disperse rhetorically connected chunks throughout a large structure.

- They are not is not chronological in structure (the chronological sequence is normally factored out);

- Contributions are not attributed (who said what is normally factored out).

- They do not convey the maturity of the map – one cannot distinguish, from the map alone, whether one map is more “sound” than another.

- They do not offer a systematic way to decide if two questions are the same, or how the maps of two related questions relate.

Some of these issues (points 3, 4) can be addressed by annotating nodes; others are not so easy to solve.

Concluding remarks

My aim in this post has been to introduce readers to the IBIS notation, and also discuss its origins, development and limitations. On one hand, a knowledge of the origins and development is valuable because it gives insight into the rationale behind the technique, which leads to a better understanding of the different ways in which it can be used. On the other, it is also important to know a technique’s limitations, if for no other reason than to be aware of these so that one can work around them.

Before signing off, I’d like to mention an observation from my experience with IBIS. The real surprise for me has been that the technique can capture most written arguments and discussions, despite having only three distinct elements and a very simple grammar. Yes, it does require some thought to do this, particularly when mapping discussions in real time. However, this cognitive “overhead” is good because it forces the mapper to think about what’s being said instead of just writing it down blind. Thoughtful transcription is the aim of the game. When done right, this results in a map that truly reflects a shared understanding of the complex (and possibly wicked) problem under discussion.

There’s no better coda to this post on IBIS than the following quote from this paper by Conklin:

…Despite concerns over the years that IBIS is too simple and limited on the one hand or too hard to use on the other, there is a growing international community who are fluent enough in IBIS to facilitate and capture highly contentious debates using dialogue mapping, primarily in corporate and educational environments…

For me that’s reason enough to improve my understanding of IBIS and its applications, and to look for opportunities to use it in ever more challenging situations.

Visualising arguments using issue maps – an example and some general comments

The aim of an opinion piece writer is to convince his or her readers that a particular idea or point of view is reasonable or right. Typically, such pieces weave facts , interpretations and reasoning into prose, wherefrom it can be hard to pick out the essential thread of argumentation. In an earlier post I showed how an issue map can help in clarifying the central arguments in a “difficult” piece of writing by mapping out Fred Brooks’ classic article No Silver Bullet. Note that I use the word “difficult” only because the article has, at times, been misunderstood and misquoted; not because it is particularly hard to follow. Still, Brooks’ article borders on the academic; the arguments presented therein are of interest to a relatively small group of people within the software development community. Most developers and architects aren’t terribly interested in the essential difficulties of the profession – they just want to get on with their jobs. In the present post, I develop an issue map of a piece that is of potentially wider interest to the IT community – Nicholas Carr’s 2003 article, IT Doesn’t Matter.

The main point of Carr’s article is that IT is becoming a utility, much like electricity, water or rail. As this trend towards commoditisation gains momentum, the strategic advantage offered by in-house IT will diminish, and organisations will be better served by buying IT services from “computing utility” providers than by maintaining their own IT shops. Although Carr makes a persuasive case, he glosses over a key difference between IT and other utilities (see this post for more). Despite this, many business and IT leaders have taken his words as the way things will be. It is therefore important for all IT professionals to understand Carr’s arguments. The consequences are likely to affect them some time soon, if they haven’t already.

Some preliminaries before proceeding with the map. First, the complete article is available here – you may want to have a read of it before proceeding (but this isn’t essential). Second, the discussion assumes a basic knowledge of IBIS (Issue-Based Information System) – see this post for a quick tutorial on IBIS. Third, the map is constructed using the open-source tool Compendium which can be downloaded here.

With the preliminaries out of the way, let’s get on with issue mapping Carr’s article.

So, what’s the root (i.e. central) question that Carr poses in the article? The title of the piece is “IT Doesn’t Matter” – so one possible root question is, “Why doesn’t IT matter?” But there are other candidates: “On what basis is IT an infrastructural technology?” or “Why is the strategic value of IT diminishing?” for example. From this it should be clear that there’s a fair degree of subjectivity at every step of constructing an issue map. The visual representation that I construct here is but one interpretation of Carr’s argument.

Out of the above (and many other possibles), I choose “Why doesn’t IT matter?” as the root question. Why? Well, in my view the whole point of the piece is to convince the reader that IT doesn’t matter because it is an infrastructural technology and consequently has no strategic significance. This point should become clearer as our development of the issue map progresses.

The ideas that respond to this question aren’t immediately obvious. This isn’t unusual: as I’ve mentioned elsewhere, points can only be made sequentially – one after the other – when expressed in prose. In some cases one may have to read a piece in its entirety to figure out the elements that respond to a root (or any other) question.

In the case at hand, the response to the root question stands out clearly after a quick browse through the article. It is: IT is an infrastructural technology.

The map with the root question and the response is shown in Figure 1.

Moving on, what arguments does Carr offer for (pros) and against (cons) this idea? A reading of the article reveals one con and four pros. Let’s look at the cons first:

- IT (which I take to mean software) is complex and malleable, unlike other infrastructural technologies. This point is mentioned, in passing, on the third page of the paper: “Although more complex and malleable than its predecessors, IT has all the hallmarks of an infrastructural technology…”

The arguments supporting the idea that IT is an infrastructural technology are:

- The evolution of IT closely mirrors that of other infrastructural technologies such as electricity and rail. Although this point encompasses the other points made below, I think it merits a separate mention because the analogies are quite striking. Carr makes a very persuasive, well-researched case supporting this point.

- IT is highly replicable. This is point needs no further elaboration, I think.

- IT is a transport mechanism for digital information. This is true, at least as far as network and messaging infrastructure is concerned.

- Cost effectiveness increases as IT services are shared. This is true too, providing it is understood that flexibility is lost when services are shared.

The map, incorporating the pros and cons is shown in Figure 2.

Now that the arguments for and against the notion that IT is an infrastructural technology are laid out, lets look at the article again, this time with an eye out for any other issues (questions) raised.

The first question is an obvious one: What are the consequences of IT being an infrastructural technology?

Another point to be considered is the role of proprietary technologies, which – by definition – aren’t infrastructural. The same holds true for custom built applications. So, this begs the question, if IT is an infrastructural technology, how do proprietary and custom built applications fit in?

The map, with these questions added in is shown in Figure 3.

Let’s now look at the ideas that respond to these two questions.

A point that Carr makes early in the article is that the strategic value of IT is diminishing. This is essentially a consequence of the notion that IT is an infrastructural technology. This idea is supported by the following arguments:

- IT is ubiquitous – it is everywhere, at least in the business world.

- Everyone uses it in the same way. This implies that no one gets a strategic advantage from using it.

What about proprietary technologies and custom apps?. Carr reckons these are:

- Doomed to economic obsolescence. This idea is supported by the argument that these apps are too expensive and are hard to maintain.

- Related to the above, these will be replaced by generic apps that incorporate best practices. This trend is already evident in the increasing number of enterprise type applications that offered as services. The advantages of these are that they a) cost little b) can be offered over the web and c) spare the client all those painful maintenance headaches.

The map incorporating these ideas and their supporting arguments is shown in Figure 4.

Finally, after painting this somewhat gloomy picture (to a corporate IT minion, such as me) Carr asks and answers the question: How should organisations deal with the changing role of IT (from strategic to operational)? His answers are:

- Reduce IT spend.

- Buy only proven technology – follow don’t lead.

- Focus on (operational) vulnerabilities rather than (strategic) opportunities.

The map incorporating this question and the ideas that respond to it is shown in Figure 5, which is also the final map (click on the graphic to view a full-sized image).

Map completed, I’m essentially done with this post. Before closing, however, I’d like to mention a couple of general points that arise from issue mapping of prose pieces.

Figure 5 is my interpretation of the article. I should emphasise that my interpretation may not coincide with what Carr intended to convey (in fact, it probably doesn’t). This highlights an important, if obvious, point: what a writer intends to convey in his or her writing may not coincide with how readers interpret it. Even worse, different readers may interpret a piece differently. Writers need to write with an awareness of the potential for being misunderstood. So, my first point is that issue maps can help writers clarify and improve the quality of their reasoning before they cast it in prose.

Issue maps sketch out the logical skeleton or framework of argumentative prose. As such, they can help highlight weak points of arguments. For example, in the above article Carr glosses over the complexity and malleability of software. This is a weak point of the argument, because it is a key difference between IT and traditional infrastructural technologies. Thus my second point is that issue maps can help readers visualise weak links in arguments which might have been obscured by rhetoric and persuasive writing.

To conclude, issue maps are valuable to writers and readers: writers can use issue maps to improve the quality of their arguments before committing them in writing, and readers can use such maps to understand arguments that have been thus committed.

Dialogue Mapping: a book review

I’ll say it at the outset: once in a while there comes along a book that inspires and excites because it presents new perspectives on old, intractable problems. In my opinion, Dialogue Mapping : Building a Shared Understanding of Wicked Problems by Jeff Conklin falls into this category. This post presents an extensive summary and review of the book.

Before proceeding, I think it is only fair that I state my professional views (biases?) upfront. Some readers of this blog may have noted my leanings towards the “people side” of project management (see this post , for example). Now, that’s not to say that I don’t use methodologies and processes. On the contrary, I use project management processes in my daily work, and appreciate their value in keeping my projects (and job!) on track. My problem with processes is when they become the only consideration in managing projects. It has been my long-standing belief (supported by experience) that if one takes care of the people side of things, the right outcomes happen more easily; without undue process obsession on part of the manager. (I should clarify that I’m not encouraging some kind of a laissez-faire, process-free approach, merely one that balances both people and processes). I’ve often wondered if it is possible to meld these two elements into some kind of “people-centred process”, which leverages the collective abilities of people in a way that facilitates and encourages their participation. Jeff Conklin’s answer is a resounding “Yes!”

Dialogue mapping is a process that is aimed at helping groups achieve a shared understanding of wicked problems – complex problems that are hard to understand, let alone solve. If you’re a project manager that might make your ears perk up; developing a shared understanding of complex issues is important in all stages of a project: at the start, all stakeholders must arrive at a shared understanding of the project goals (eg, what are we trying to achieve in this project?); in the middle, project team members may need to come to a common understanding (and resolution) of tricky implementation issues; at the end, the team may need to agree on the lessons learned in the course of the project and what could be done better next time. But dialogue mapping is not restricted to project management – it can be used in any scenario involving diverse stakeholders who need to arrive at a common understanding of complex issues. This book provides a comprehensive introduction to the technique.

Although dialogue mapping can be applied to any kind of problem – not just wicked ones – Conklin focuses on the latter. Why? Because wickedness is one of the major causes of fragmentation: the tendency of each stakeholder to see a problem from his or her particular viewpoint ignoring other, equally valid, perspectives. The first chapter of this book discusses fragmentation and its relationship to wickedness and complexity. Fragmentation is a symptom of complexity- one would not have diverse, irreconcilable viewpoints if the issues at hand were simple. According to Conklin, fragmentation is a function of problem wickedness and social complexity, i.e. the diversity of stakeholders. Technical complexity is also a factor, but a minor one compared to the other two. All too often, project managers fall into the trap of assuming that technical complexity is the root cause of many of their problems, ignoring problem complexity (wickedness) and social complexity. The fault isn’t entirely ours; the system is partly to blame: the traditional, process driven world is partially blind to the non-technical aspects of complexity. Dialogue mapping helps surface issues that arise from these oft ignored dimensions of project complexity.

Early in the book, Conklin walks the reader through the solution process for a hypothetical design problem. His discussion is aimed at highlighting some limitations of the traditional approach to problem solving. The traditional approach is structured; it works methodically through gathering requirements, analysing them, formulating a solution and finally implementing it. In real-life, however, people tend to dive headlong into solving the problem. Their approach is far from methodical – it typically involves jumping back and forth between hypothesis formulation, solution development, testing ideas, following hunches etc. Creative work, like design, cannot be boxed in by any methodology, waterfall or otherwise. Hence the collective angst on how to manage innovative product development projects. Another aspect of complexity arises from design polarity; what’s needed (features requested) vs. what’s feasible(features possible) – sometimes called the marketing and development views. Design polarity is often the cause of huge differences of opinion within a team; that is, it manifests itself as social complexity.

Having set the stage in the first chapter, the rest of the book focuses on describing the technique of dialogue mapping. Conklin’s contention is that fragmentation manifests itself most clearly in meetings – be they project meetings, design meetings or company board meetings. The solution to fragmentation must, therefore, focus on meetings. The solution is for the participants to develop a shared understanding of the issues at hand, and a shared commitment to a decision and action plan that addresses them. The second chapter provides an informal discussion of how these are arrived at via dialogue that takes place in meetings. Dialogue mapping provides a process – yes, it is a process – to arrive at these.

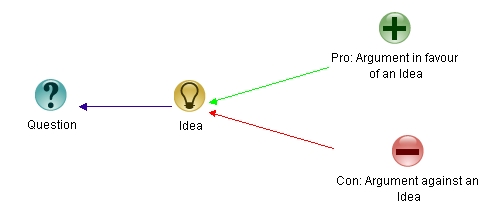

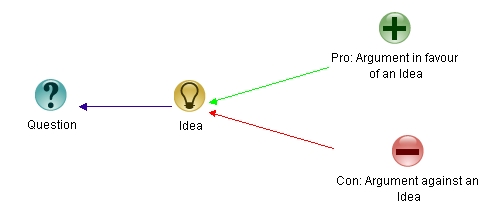

The second chapter also introduces some of the elements that make up the process of dialogue mapping. The first of these is a visual notation called IBIS (Issue Based Information System). The IBIS notation was invented by Horst Rittel, the man who coined the term wicked problem. IBIS consists of three elements depicted in Figure 1 below – Issues (or questions), Ideas (that generally respond to questions) and Arguments (for and against ideas – pros and cons) – which can be connected according to a specified grammar (see this post for a quick introduction to IBIS or see Paul Culmsee’s series of posts on best practices for a longer, far more entertaining one). Questions are at the heart of dialogues (or meetings) that take place in organisations – hence IBIS, with its focus on questions, is ideally suited to mapping out meeting dialogues.

Figure 1: IBIS Elements

The basic idea in dialogue mapping is that a skilled facilitator maps out the core points of the dialogue in real-time, on a shared display which is visible to all participants. The basic idea is that participants see their own and collective contributions to the debate, while the facilitator fashions these into a coherent whole. Conklin’s believes that this can be done, no matter how complex the issues are or how diverse and apparently irreconcilable the opinions. Although I have limited experience with the technique, I believe he is right: IBIS in the hands of a skilled facilitator can help a group focus on the real issues, blowing away the conversational chaff. Although the group as a whole may not reach complete agreement, they will at least develop a real understanding of other perspectives. The third chapter, which concludes the first part of the book, is devoted to an example that illustrates this point.

The second part of the book delves into the nuts and bolts of dialogue mapping. It begins with an introduction to IBIS – which Conklin calls a “tool for all reasons.” The book provides a nice informal discussion, covering elements, syntax and conventions of the language. The coverage is good, but I have a minor quibble : one has to read and reread the chapter a few times to figure out the grammar of the language. It would have been helpful to have an overview of the grammar collected in one place (say in a diagram, like the one shown in Figure 2). Incidentally, Figures 1 and 2 also show how an IBIS map is structured: starting from a root question (placed on the left of the diagram) and building up to the right as the discussion proceeds.

A good way to gain experience with IBIS is to use it to create issue maps of arguments presented in articles. See this post for an example of an issue map based on Fred Brooks’ classic article, No Silver Bullet.

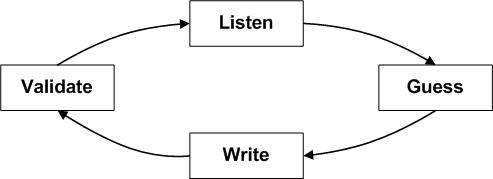

Dialogue mapping is issue mapping plus facilitation. The next chapter – the fifth one in the book – discusses facilitation skills required for dialogue mapping. The facilitator (or technographer, as the person is sometimes called) needs to be able to listen to the conversation, guess at the intended meaning, write (or update) the map and validate what’s written; then proceed through the cycle of listening, guessing, writing and validating again as the next point comes up and so on. Conklin calls this the dialogue mapping listening cycle (see Figure 3 below). As one might imagine, this skill, which is the key to successful dialogue mapping, takes lots of practice to develop. In my experience, a good way to start is by creating IBIS maps of issues discussed in meetings involving a small number of participants. As one gains confidence through practice, one shares the display thereby making the transition from issue mapper to dialogue mapper.

One aspect of the listening cycle is counter-intuitive – validation may require the facilitator to interrupt the speaker. Conklin emphasises that it is OK to do so as long as it is done in the service of listening. Another important point is that when capturing a point made by someone, the technographer will need to summarise or interpret the point. The interpretation must be checked with the speaker. Hence validation – and the interruption it may entail – is not just OK, it is absolutely essential. Conklin also emphasises that the facilitator should focus on a single person in each cycle – it is possible to listen to only one person at a time.

A side benefit of interrruption is that it slows downs the dialogue. This is a good thing because everyone in the group gets more time to consider what’s on the screen and how it relates (or doesn’t) to their own thoughts. All too often, meetings are rushed, things are done in a hurry, and creative creative ideas and thoughts are missed in the bargain. A deliberate slowing down of the dialogue counters this.

The final part of the book – chapters six through nine – are devoted to advanced dialogue mapping skills.

The sixth chapter presents a discussion of the types of questions that arise in most meetings. Conklin identifies seven types of questions:

Deontic: These are questions that ask what should be done in order to deal with the issue at hand. For example: What should we do to improve our customer service? The majority of root questions (i.e. starting questions) in an IBIS map are deontic.

Instrumental: These are questions that ask how something should be done. For example: How can we improve customer service? These questions generally follow on from deontic questions. Typically root questions are either deontic or instrumental.

Criterial: These questions ask about the criteria that any acceptable ideas must satisfy. Typically ideas that respond to criterial questions will serve as a filter for ideas that might come up. Conklin sees criterial and instrumental questions as being complementary. The former specify high-level constraints (or criteria) for ideas whereas the latter are nuts-and-bolts ideas on how something is to be achieved. For example, a criterial question might ask: what are the requirements for improving customer service or how will we know that we have improved customer service.

Conklin makes the point that criterial questions typically connect directly to the root question. This makes sense: the main issue being discussed is usually subject ot criteria or constraints. Further, ideas that respond to criterial questions (in other words, the criteria) have a correspondence with arguments for and against the root questions. This makes sense: the pros and cons that come up in a meeting would generally correspond to the criteria that have been stated. This isn’t an absolute requirement – there’s nothing to say that all arguments must correspong to at least one criterion – but it often serves as a check on whether a discussion is taking all constraints into account.

Conceptual: These are questions that clarify the meaning of any point that’s raised. For example, what do we mean by customer service? Conklin makes the point that many meetings go round in circles because of differences in understanding of particular terms. Conceptual questions surface such differences.

Factual: These are questions of fact. For example: what’s the average turnaround time to respond to customer requests? Often meetings will debate such questions without having any clear idea of what the facts are. Once a factual question is identified as such, it can be actioned for someone to do research on it thereby saving a lot of pointless debate

Background: These are questions of context surrounding the issue at hand. An example is: why are we doing this initiative to improve customer service? Ideas responding to such questions are expected to provide the context as to why something has become an issue.

Stakeholder: These are the “who” questions. An example: who should be involved in the project? Such questions can be delicate in situations where there are conflicting interests (cross-functional project, say), but need to be asked in order to come up with a strategy to handle differences opinion. One can’t address everyone’s concerns until one knows who all constitute “everyone”.

Following the classification of questions, Conklin discusses the concept of a dialogue meta-map – an overall pattern of how certain kinds of questions naturally follow from certain others. The reader may already be able to discern some of these patterns from the above discussion of question types. Also relevant here are artful questions – open questions that keep the dialogue going in productive directions.

The seventh chapter is entitled Three Moves of Discourse. It describes three conversational moves that propel a discussion forward, but can also upset the balance of power in the discussion and evoke strong emotions. These moves are:

- Making an argument for an idea or proposal (a Pro)

- Making an argument against an idea (a Con)

- Challenging the context of the entire discussion.

Let’s look at the first two moves to start with. In an organisation, these moves have a certain stigma attached to them: anyone making arguments for or against an idea might be seen as being opinionated or egotistical. The reason is because these moves generally involve contradicting someone else in the room. Conklin contends that dialogue mapping takes removes these negative connotations because the move is seen as just another node in the map. Once on the map, it is no longer associated with any person – it is objectified as an element of the larger discussion. It can be discussed or questioned just as any other node can.

Conklin refers to the last move – challenging the context of a discussion – as “grenade throwing.” This is an apt way of describing such questions because they have the potential to derail the discussion entirely. They do this by challenging the relevance of the root question itself. But dialogue mapping takes these grenades in its stride; they are simply captured as any another conversational move – i.e. a node on the map, usually a question. Better yet, in many cases further discussion shows how these questions might connect up with the rest of the map. Even if they don’t, these “grenade questions” remain on the map, in acknowledgement of the dissenter and his opinion. Dialogue mapping handles such googlies (curveballs to baseball aficionados) with ease, and indicates how they might connect up with the rest of the discussion – but connection is neither required nor always desirable. It is OK to disagree, as long as it is done respectfully. This is a key element of shared understanding – the participants might not agree, but they understand each other.

Related to the above is the notion of a “left hand move”. Occasionally a discussion can generate a new root question which, by definition, has to be tacked on to the extreme left of the map. Such a left hand move is extremely powerful because it generally relates two or more questions or ideas that were previously unrelated (some of them may even have been seen as a grenade).

By now it should be clear that dialogue mapping is a technique that promotes collaboration – as such it works best in situations where openness, honesty and transparency are valued. In the penultimate chapter, the author discusses some situations in which it may not be appropriate to use the technique. Among these are meetings in which decisions are made by management fiat. Other situations in which it may be helpful to “turn the display off” are those which are emotionally charged or involve interpersonal conflict. Conklin suggests that the facilitator use his or her judgement in deciding where it is appropriate and where it isn’t.

In the final chapter, Conklin discusses how decisions are reached using dialogue mapping. A decision is simply a broad consensus to mark one of the ideas on the map as a decision. How does one choose the idea that is to be anointed as the group’s decision? Well quite obviously: the best one. Which one is that? Conklin states, the best decision is the one that has the broadest and deepest commitment to making it work. He also provides a checklist for figuring out whether a map is mature enough for a decision to be made. But the ultimate decision on when a decision (!) is to be made is up to group. So how does one know when the time is right for a decision? Again, the book provides some suggestions here, but I’ll say no more except to hint at them by paraphrasing from the book: “What makes a decision hard is lack of shared understanding. Once a group has thoroughly mapped a problem (issues) and its potential solutions (ideas) along with their pros and cons, the decision itself is natural and obvious.”

Before closing, I should admit that my experience with dialogue mapping is minimal – I’ve done it a few times in small groups. I’m not a brilliant public speaker or facilitator, but I can confirm that it helps keep a discussion focused and moving forward. Although Conklin’s focus is on dialogue mapping, one does not need to be a facilitator to benefit from this book; it also provides a good introduction to issue mapping using IBIS. In my opinion, this alone is worth the price of admission. Further, IBIS can also be used to augment project (or organisational) memory. So this book potentially has something for you, even if you’re not a facilitator and don’t intend to use IBIS in group settings.

This brings me to the end of my long-winded summary and review of the book. My discussion, as long as it is, does not do justice to the brilliance of the book. By summarising the main points of each chapter (with some opinions and annotations for good measure!), I have attempted to convey a sense of what a reader can expect from the book. I hope I’ve succeeded in doing so. Better yet, I hope I have convinced you that the book is worth a read, because I truly believe it is.