Archive for the ‘Issue Based Information System’ Category

Why visual representations of reasoning are more effective than prose

At work I’m often saddled with tasks that involve writing business documents such as project proposals, business cases, technology evaluations etc. Typically these are aimed at conveying positions or ideas to a specific audience. For example, a business case might detail the rationale behind (and hence the justification for) a project to executive management. The hardest part of composing these documents is the flow: how ideas are introduced, explained and transitioned one after the other. (Incidentally, writing business documents is composition – like music or art – let no one tell you otherwise.) The organisation of a document has to be carefully thought through because it is hard to convey complex, interconnected ideas in writing. Anyone who has laboured through a piece of reasoning in prose form is familiar with this problem. In an earlier post I discussed, via example, the utility of issue mapping – a visual representation of reasoning – in clarifying complex issues that are presented in writing. In this post I explore reasons why issue maps – or other visual representations of reasoning – are superior to prose when it comes to conveying ideas. Towards the end, I also highlight some potential uses of visual representations in project management.

The basic problem with prose is that the relationships between ideas are not immediately evident. In a paper entitled Enhancing Deliberation Through Computer Supported Argument Mapping Tim van Gelder states,

Extracting the structure of evidential relationships from reasoning as typically presented in prose is very difficult and most of the time we do it badly. This can be easily illustrated, in a kind of exercise we have done informally many times in workshops. Take any group of people sufficiently trained in reasoning and argument mapping that they are quite able to create argument maps to make explicit whatever reasoning they have in mind. Now give them a sample of good argumentative prose, such as a well-argued opinion piece from the newspaper. Ask them to figure out what the reasoning is, and to re-present it in an argument map. This usually takes about 20-30 minutes, during which time you can enjoy watching the participants strike various Rodinesque postures of intense concentration, wipe their sweaty palms, etc.. Then compare the resulting argument maps. You’ll find that you have as many different argument maps as there are people doing the exercise; in many cases the maps will be wildly different…

Although the paper is talks about argument mapping, the discussion applies just as well to issue mapping. He goes on to say,

Take any group of people sufficiently trained to be able to be read argument maps. (This training usually takes not more than a few minutes.) Present them with an argument map, and ask them to identify the reasoning presented in the map, and represent it in whatever form they like (map, prose, point-form etc.). This is a very simple task and usually takes almost no time; indeed, it is so trivial that the hard part is getting the participants to go through the motions when no intellectual challenge is involved. Ask them questions designed to elicit the extent to which they have correctly identified the structure of the reasoning presented by the map (e.g., how many distinct reasons are presented for the main conclusion?). You’ll find that they all understand exactly what the reasoning is, and ipso facto all have the same sense of the reasoning…

The point is simple: visual representations of reasoning are designed to present reasoning; prose isn’t.

Van Gelder then asks the question: why are visual representations better than prose? In answer, he makes the following points:

1. Prose has to be interpreted: As prose is not expressly designed to represent reasoning, readers have to decode relationships and connections between ideas. The choices they make will depend on individual interpretations of the meaning of words used and the grammatical structure of the piece. These interpretations will in turn depend on facility with the language, vocabulary etc. In contrast, visual notations such as IBIS (used in issue mapping) have few elements and very simple grammars. Simplicity slays ambiguity.

2. Prose neglects representational resources: Prose is a stream of words – it does not use other visual elements such as colour, shape, position or any graphical structures (trees, nodes, connectors). The brain processes comprehends such elements – and the visually apparent relationships between them – much faster than it can interpret prose. Hence the structured use of these can lead to faster comprehension. Van Gelder also adds that in the case of prose:

…Helpful authors (of prose) will assist readers in the difficult process of interpretation by providing verbal cues (for example, logical indicators such as “therefore”), although it is quite astonishing how frugal most authors are in providing such cues….

This is true, and I’d add that writers – particularly those who write analytical pieces – tend to be frugal because they are taught to be so.

3. Prose is sequential, arguments aren’t: Reasoning presented in written form flows linearly – i.e. concepts and ideas appear in sequence. A point that’s made on one page may be related to something that comes up five pages later, but the connections will not be immediately apparent unless the author specifically draws attention to it. Jeff Conklin makes the same point about conversations in this presentation: conversations are linear, one comment follows the other; however the issues that come up in a conversation are typically related in a non-linear way. Visual maps of reasoning expose these non-linear connections between issues in a very apparent and easy-to-follow way. See this map of a prose piece or this map of a conversation, for example.

4. Metaphors cannot be visually displayed in prose: According to the linguist / philosopher George Lakoff, metaphors are central to human understanding. Further, metaphors are grounded in our physical experience because our brains take input from the rest of our bodies (see this interview with Lakoff for more). For this reason, most of the metaphors we use to express reasoning relate to physical experience and sensation: strength or weakness of an argument, support for a position, weight of an idea, external pressure etc. Van Gelder claims that visual representations can depict these metaphors in a more natural way: for instance, in IBIS maps, cons are coloured red (Stop) whilst pros are green (Go).

The above points are taken from van Gelder’s paper, but I can think of a few more:

5. Visual representations have less ambiguity: All visual representations of reasoning that I’ve come across – mind maps, issue maps, argument maps etc – excel at displaying relationships between ideas in an unambiguous manner. One reason for this is that visual representations generally have a limited syntax and grammar, as a consequence of which a given relationship can be expressed in only a small number of ways (usually one!). Hence there is little or no ambiguity in depicting or interpreting relationships in a visual representation. This is not the case with prose, where much depends on the skill and vocabulary of the writer and reader.

6. Visual representations can present reasoning “at a glance”: A complex argument which takes up several pages of prose can often be captured in a single page using visual notations. Such visual representations -if properly constructed – are also more intuitive than the corresponding prose representation. See my post entitled, Beyond words: visualising arguments using issue maps for an example.

7. Visual representations can augment organisational memory A well structured archive of knowledge maps is so much more comprehensible than reams of documentation. Here are a couple of reasons why:

- Maps, unlike written documents, can capture the essence of a discussion minus all the conversational chaff.

- Maps can be structured to show the logical relationships or interconnections between multiple documents: i.e. as maps of organisational knowledge. Much like geographical maps, these can help knowledge workers navigate their way through vast tracts of organisational knowledge

See my post on knowledge capture using issue maps for much more on this.

8. Visual representations can catalyse knowledge creation: Visual representations, when used collaboratively, can catalyse the creation of knowledge. This is the basis of the technique of dialogue mapping – see this post for a simple example of dialogue mapping using IBIS. A visual representation serves as a focal point that captures a group’s collective reasoning and understanding of an issue as it evolves. Even more, the use of such representations in design discussions can foster creativity in much the same way as in art. In fact, Al Selvin refers to Compendium – the tool and methodology used in dialogue mapping – as an enabler of Knowledge Art. I’m currently reading some of Selvin’s writings on this, and will soon write a post summarising some of his ideas. Stay tuned.

If you’re a project manager and have read this far, perhaps you’re wondering how this stuff might be relevant to your day-to-day work. Well, in a couple of ways at least:

- Visual representations can serve as a succinct project memory. A practical way to start is by using issue mapping to capture meeting minutes. One can also use it to summarise meetings after they have taken place, but doing it in real-time is better because one can seek clarifications on the spot. Better still – project the map on to a screen and become a dialogue mapper.

- Maps can be used in real-time to to facilitate collaborative design – or create knowledge art – as discussed in point 8 above.

To summarise, then: visual representations of reasoning are more effective than prose because they are better at capturing the nonlinear structure of arguments; easier to interpret; leverage visual metaphors; depict relationships effectively and present arguments in a succinct yet intuitively appealing way. Above all, visual representations can facilitate collaborative creativity – something that prose simply cannot do.

Beyond words: visualising arguments using issue maps

Anyone who has struggled to follow a complex argument in a book or article knows from experience that reasoning in written form can be hard to understand. Perhaps this is why many people prefer to learn by attending a class or viewing a lecture rather than by reading. The cliché about a picture being worth more than a large number of words has a good deal of truth to it: visual representations can be helpful in clarifying complex arguments. In a recent post, I presented a quick introduction to a visual issue mapping technique called IBIS (Issue Based Information System), discussing how it could be used on complex projects. Now I follow up by demonstrating its utility in visualising complex arguments such as those presented in research papers. I do so by example: I map out a well known opinion piece written over two decades ago – Fred Brooks’ classic article, No Silver Bullet, (abbreviated as NSB in the remainder of this article).

[Note: those not familiar with IBIS may want to read one of the introductions listed here before proceeding]

Why use NSB as an example for argument mapping? Well, for a couple of reasons:

- It deals with issues that most software developers have grappled with at one time or another.

- The piece has been widely misunderstood (by Brooks’ own admission – see his essay entitled No Silver Bullet Refired, published in the anniversary edition of The Mythical Man Month).

First, very briefly, for those who haven’t read the article: NSB presents reasons why software development is intrinsically hard and consequently conjectures that “silver bullet” solutions are impossible, even in principle. Brooks defines a silver bullet solution for software engineering as any tool or technology that facilitates a tenfold improvement in productivity in software development.

To set the context for the discussion and to see the angle from which Brooks viewed the notion of a silver bullet for software engineering, I can do no better than quote the first two paragraphs of NSB:

Of all the monsters that fill the nightmares of our folklore, none terrify more than werewolves, because they transform unexpectedly from the familiar into horrors. For these, one seeks bullets of silver that can magically lay them to rest.

The familiar software project, at least as seen by the non-technical manager, has something of this character; it is usually innocent and straightforward, but is capable of becoming a monster of missed schedules, blown budgets, and flawed products. So we hear desperate cries for a silver bullet—something to make software costs drop as rapidly as computer hardware costs do.

The first step in mapping out an argument is to find the basic issue that it addresses. That’s easy for NSB; the issue, or question, is: why is there no silver bullet for software development?

Brooks attempts to answer the question via two strands:

- By examining the nature of the essential (intrinsic or inherent) difficulties in developing software.

- By examining the silver bullet solutions proposed so far.

That gives us enough for us to begin our IBIS map …

The root node of the map – as in all IBIS maps – is a question node. Responding to the question, we have an idea node (Essential difficulties) and another question node (What about silver bullet solutions proposed to date). We also have a note node which clarifies what is meant by a silver bullet solution.

The point regarding essential difficulties needs elaboration, so we ask the question– What are essential difficulties?

According to Brooks, essential difficulties are those that relate to conceptualisation – i..e. design. In contrast, accidental (or non-essential) difficulties are those pertaining to implementation. Brooks examines the nature of essential difficulties – i.e. the things that make software design hard. He argues that the following four properties of software systems are the root of the problem:

Complexity: Beyond the basic syntax of a language, no two parts of a software system are alike – this contrasts with other products (such as cars or buildings) where repeated elements are common. Furthermore, software has a large number of states, multiplied many-fold by interactions with other systems. No person can fully comprehend all the consequences of this complexity. Furthermore, no silver bullet solution can conquer this problem because each program is complex in unique ways.

Conformity: Software is required to conform to arbitrary business rules. Unlike in the natural sciences, these rules may not (often do not!) have any logic to them. Further, being the newest kid on the block, software often has to interface with disparate legacy systems as well. Conformity-related issues are external to the software and hence cannot be addressed by silver bullet solutions.

Changeability: Software is subject to more frequent change than any other part of a system or even most other manufactured products. Brooks speculates that this is because most software embodies system functionality (i.e. the way people use the system), and functionality is subject to frequent change. Another reason is that software is intangible (made of “thought stuff”) and perceived as being easy to change.

Invisibility: Notwithstanding simple tools such as flowcharts and modelling languages, Brooks argues that software is inherently unvisualisable. The basic reason for this is that software – unlike most products (cars, buildings, silicon chips, computers) – has no spatial form.

These essential properties are easily captured in summary form in our evolving argument map:

Brooks’ contention is that software design is hard because every software project has to deal with unique manifestations of these properties.

Brooks then looks at silver bullet solutions proposed up to 1987 (when the article was written) and those on the horizon at the time. He finds most of these address accidental (or non-intrinsic) issues – those that relate to implementation rather than design. They enhance programmer productivity – but not by the ten-fold magnitude required for them to be deemed silver bullets. Brooks reckons this is no surprise: the intrinsic difficulties associated with design are by far the biggest obstacles in any software development effort.

In the map I club all these proposed solutions under “silver bullet solutions proposed to date.”

Incorporating the above, the map now looks like:

[For completeness here’s a glossary of abbreviations: OOP – Object-oriented programming; IDE – Integrated development environment; AI – Artificial intelligence]

The proposed silver bullets lead to incremental improvements in productivity, but they do not address the essential problem of design. Further, some of the solutions have restricted applicability. These points are captured as pros and a cons in the map (click on the map to view a larger image):

It is interesting to note that in his 1997 article, No Silver Bullet Refired , which revisited the questions raised in NSB, Brooks found that the same conclusions held true. Furthermore, at a twentieth year retrospective panel discussion that took place during the 22nd International Conference on Object-Oriented Programming, Systems, Languages, and Applications, panellists again concluded that there’s no silver bullet – and none likely.

Having made his case that no silver bullet exists, and that none are likely, Brooks finishes up by outlining a few promising approaches to tackling the design problem. The first one, Buy don’t build, is particularly prescient in view of the growth of the shrink-wrapped software market in the two decades since the first publication of NSB. The second one – rapid prototyping and iterative/incremental development – is vindicated by the widespread adoption and mainstreaming of agile methodologies. The last one, nurture talent, perhaps remains relatively ignored. It should be noted that Brooks considers these approaches promising, but not silver bullets; he maintains that none of these by themselves can lead to a tenfold increase in productivity.

So we come to the end of NSB and our map, which now looks like (click on the map to view a larger image):

The map captures the essence of the argument in NSB – a reader can see, at a glance, the chain of reasoning and the main points made in the article. One could embellish the map and improve readability by:

- Adding in details via note nodes, as I have done in my note explaining what is meant by a silver bullet.

- Breaking up the argument into sub-maps – the areas highlighted in yellow in each of the figures could be hived off into their own maps.

But these are details; the essence of the argument in NSB is captured adequately in the final map above.

In this post I have attempted to illustrate, via example, the utility of IBIS in constructing maps of complicated arguments. I hope I’ve convinced you that issue maps offer a simple way to capture the essence of a written argument in an easy-to-understand way.

Perhaps the cliche should be revised: a picture may be worth a thousand words, but an issue map is worth considerably more.

IBIS References on the Web

For a quick introduction, I recommend Jeff Conklin’s introduction to IBIS on the Cognexus site (and the links therein) or my piece on the use of IBIS in projects. If you have some time, I highly recommend Paul Culmsee’s excellent series of posts: the one best practice to rule them all.

Capturing project knowledge using issue maps

Here’s a question that’s been on my mind for a while: Why do organisations find it difficult to capture and transmit knowledge created in projects?

I’ll attempt an answer of sorts in this post and point to a solution of sorts too – taking a bit of a detour along the way, as I’m often guilty of doing…

Let us first consider how knowledge is generated on projects. In project environments, knowledge is typically created in response to a challenge faced. The challenge may be the project objective itself, in which case the knowledge created is embedded in the product or service design. On the other hand it could be a small part of the project: say, a limitation of the technology used, in which case the knowledge might correspond to a workaround discovered by a project team member. In either case, the existence of an issue or challenge is a precondition to the creation of knowledge. The project team (or a subset of it) decides on how the issue should be tackled. They do so incrementally; through exploration, trial and error and discussion – creating knowledge in the bargain.

In a nutshell: knowledge is created as project members go through a process of discovery. This process may involve the entire team (as in the first example) or a very small subset thereof (as in the second example, where the programmer may be working alone). In both cases, though, the aim is to understand the problem, explore potential solutions and find the “best” one thus creating new knowledge.

Now, from the perspective of project and organisational learning, project documentation must capture the solution and the process by which it was developed. Typically, most documentation tends to focus on the former, neglecting the latter. This is akin to presenting a solution to a high school mathematics problem without showing the intervening steps. My high school maths teacher would’ve awarded me a zero for such an effort regardless of the whether or not my answer was right. And with good reason too: the steps leading up to a solution are more important than the solution itself. Why? Because the steps illustrate the thought processes and reasoning behind the solution. So it is with project documentation. Ideally, documentation should provide the background, constraints, viewpoints, arguments and counter-arguments that go into the creation of project knowledge.

Unfortunately, it seldom does.

Why is this so? An answer can be found in a farsighted paper, entitled Designing Organizational Memory: Preserving Intellectual Assets in a Knowledge Economy, published by Jeff Conklin 1997. In the paper Conklin draws a distinction between formal and informal knowledge; terms that correspond to the end-result and the process discussed in the previous paragraph.To quote from his paper, formal knowledge is the “…stuff of books, manuals, documents and training courses…the primary work product of the knowledge worker…” Conklin notes that, “Organisations routinely capture formal knowledge; indeed, they rely on it – without much success – as their organizational memory.” On the other hand, informal knowledge is, “the knowledge that is created and used in the process of creating formal results…It includes ideas, facts, assumptions, meanings, questions, decisions, guesses, stories and points of view. It is as important in the work of the knowledge worker as formal knowledge is, but it is more ephemeral and transitory…” As a consequence, informal knowledge is elusive; it rarely makes it into documents.

Dr. Conklin lists two reasons why organisations (which includes temporary organisations such as projects) fail to capture informal knowledge. These are:

- Business culture values results over process. In his words, “One reason for the widespread failure to capture informal knowledge is that Western culture has come to value results – the output of work process – far above the process itself, and to emphasise things over relationships.”

- The tools of knowledge workers do not support the process of knowledge work – that is, most tools focus on capturing formal knowledge (the end result of knowledge work) rather than informal knowledge (how that end result was achieved – the “steps” in the solution, so to speak).

The key to creating useful documentation thus lies in capturing informal knowledge. In order to do that, this elusive form of knowledge must first be made explicit – i.e. expressible in words and pictures. Here’s where the notion of shared understanding, discussed in my previous post comes into play.

To quote again from Conklin’s paper, “One element of creating shared understanding is making informal knowledge explicit. This means surfacing key ideas, facts, assumptions, meanings, questions, decisions, guesses, stories, and points of view. It means capturing and organizing this informal knowledge so that everyone has access to it. It means changing the process of knowledge work so that the focus is on creating and managing a shared display of the group’s informal thinking and learning. The shared display is the transparent vehicle for making informal knowledge explicit.”

The notion of a shared display is central to the technique of dialogue mapping, a group facilitation technique that can help a diverse group achieve a shared understanding of a problem. Dialogue mapping uses a visual notation called IBIS (short for Issue Based Information System) to capture the issues, ideas and arguments that come up in a meeting (see my previous post for a quick introduction to dialogue mapping and a crash-course in IBIS). As far as knowledge capture is concerned, I see two distinct uses of IBIS . They are:

- As Conklin suggests, IBIS maps can be used to surface and capture informal knowledge in real-time, as it is being generated in a discussion between two or more people.

- It can also be used in situations where one person researches and finds a solution to a challenge. In this case the person could use IBIS to capture background, approaches tried, the pros and cons of each – i.e. the process by which the solution was arrived at.

This, together with the formal stuff – which most project organisations capture more than adequately – should result in documents that provide a more complete view of the knowledge generated in projects.

Now, in a previous post (linked above) I discussed an example of how dialogue mapping was used on a real-life project challenge: how best to implement near real-time updates to a finance data mart. The final issue map, which was constructed using a mapping tool called Compendium, is reproduced below:

Example Issue Map

The map captures not only the decisions made, but also the options discussed and the arguments for and against each of the options. As such, it captures the decision along with the context, process and rationale behind it. In other words, it captures formal and informal knowledge pertaining to the decision. In this simple case, IBIS succeeded in making informal knowledge explicit. Project teams down the line can understand why the decision was made, from both a technical and business perspective.

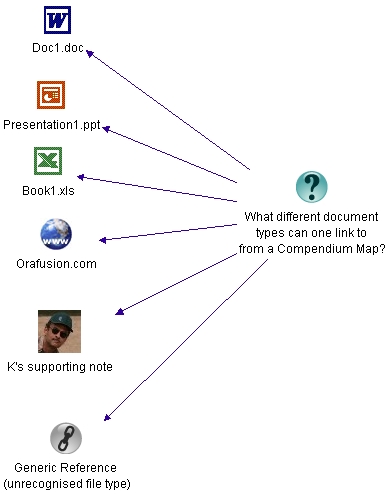

It is worth noting that Compendium maps can reference external documents via Reference Nodes, which, though less important for argumentation, are extremely useful for documentation. Here is an illustration of how references to external documents can be inserted in an IBIS map through reference node:

Links to external docs

As illustrated, this feature can be used to link out to a range of external documents – clicking on the reference node in a map (not the image above!) opens up the external document. Exploiting this, a project document can operate at two levels: the first being an IBIS map that depicts the relationships between issues, ideas and arguments, and the second being supporting documents that provide details on specific nodes or relationships. Much of the informal knowledge pertaining to the issue resides in the first level – i.e. in the relationships between nodes – and this knowledge is made explicit in the map.

To conclude, it is perhaps worth summarising the main points of this post. Projects generate new knowledge through a process in which issues and ideas are proposed, explored and trialled. Typically, most project documentation captures the outcome (formal knowledge), neglecting much of the context, background and process of discovery (informal knowledge). IBIS maps offer the possibility of capturing both aspects of knowledge, resulting in a greatly improved project (and hence organisational) memory.