Archive for the ‘Issue Based Information System’ Category

Issues, Ideas and Arguments: A communication-centric approach to tackling project complexity

I’ve written a number of posts on complexity in projects, covering topics ranging from conceptual issues to models of project complexity. Despite all that verbiage, I’ve never addressed the key issue of how complexity should be handled. Methodologists claim, with some justification, that complexity can be tamed by adequate planning together with appropriate controlling and monitoring as the project progresses. Yet, personal experience – and the accounts of many others – suggests that the beast remains untamed. A few weeks ago, I read this brilliant series of articles by Paul Culmsee, where he discusses a technique called Dialogue Mapping which, among other things, may prove to be a dragon-slayer. In this post I present an overview of the technique and illustrate its utility in real-life project situations.

First a brief history: dialogue mapping has its roots in wicked problems – problems that are hard to solve, or even define, because they satisfy one or more of these criteria. (Note that there is a relationship between problem wickedness and project complexity: projects that set out to address or solve wicked problems are generally complex but the converse is not necessarily true – see this post for more). Over three decades ago, Horst Rittel – the man who coined the term “wicked problem” – and his colleague Werner Kunz developed a technique called Issue Based Information System (IBIS) to aid in the understanding of such problems. IBIS is based on the premise that wicked problems – or any contentious issues – can be understood by discussing them in terms of three essential elements: issues (or questions), ideas (or answers) and arguments (for or against ideas). IBIS was subsequently refined over the years by various research groups and independent investigators. Jeff Conklin, the inventor of dialogue mapping, was one of the main contributors to this effort.

Now, the beauty of IBIS is that it is very easy to learn. Basically it has only the three elements mentioned earlier – issues, ideas and arguments – and these can be connected only in ways specified by the IBIS grammar. The elements and syntax of the language can be illustrated in half a page – as I shall do in a minute. Before doing so, I should mention that there is an excellent, free software tool – Compendium – that supports the IBIS notation. I use it in the discussion and demo below. I recommend that you download and install Compendium before proceeding any further.

Go on, I’ll wait for you…

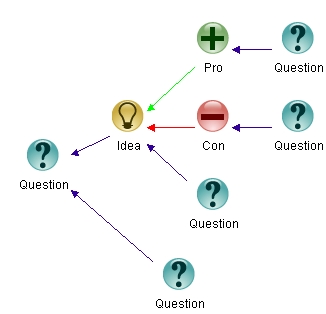

OK, let’s begin. IBIS has three elements which are illustrated in the Compendium map below:

Figure 1: IBIS Elements

The elements are:

Question: an issue that’s being discussed or analysed. Note that the term “question” is synonymous with “issue”

Idea: a response to a question. An idea responds to a question in the sense that it offers a potential resolution or clarification of the question.

Argument: an argument in favour of or against an idea (a pro or a con)

The arrows show links or relationships between elements.

That’s it as far as elements of IBIS are concerned.

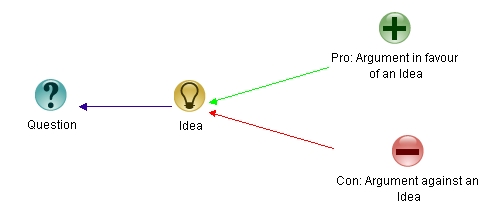

The IBIS grammar specifies the legal ways in which elements can be linked. The rules are nicely summarised in the following diagram:

In a nutshell, the rules are:

- Any element (question, idea or agument) can be questioned.

- Ideas respond to questions.

- Arguments make the case for and against ideas. Note that questions cannot be argued!

Simple, isn’t it? Essentially that’s all there is to IBIS.

So what’s IBIS got to do with dialogue mapping? Well, dialogue mapping is facilitation of a group discussion using a shared display – a display that everyone participating in the discussion can see and add to. Typically the facilitator drives – i.e. modifies the display – seeking input from all participants, using the IBIS notation to capture the issues, ideas and arguments that come up. . This synchronous, or real-time, application of IBIS is described in Conklin’s book, Dialogue Mapping: Building Shared Understanding of Wicked Problems (An absolute must-read if you manage on complex projects with diverse stakeholders). For completeness, it is worth pointing out that IBIS can also be used asynchronously – for example, in dissecting arguments presented in papers and articles. This application of IBIS – which is essentially dialogue mapping minus facilitation – is sometimes called issue mapping.

I now describe a simple but realistic application of dialogue mapping, adapted from a real-life case. For brevity, I won’t reproduce the entire dialogue. Instead I’ll describe how a dialogue map develops as a discussion progresses. The example is a simple illustration of how IBIS can be used to facilitate a shared understanding (and solution) of a problem.

All set? OK, let’s go…

The situation: Our finance data mart is updated overnight through a batch job that takes a few hours. This is good enough for most purposes. However, a small (but very vocal!) number of users need to be able to report on transactions that have occurred within the last hour or so – waiting until the next day, especially during month-end, is simply not an option. The dev team had to figure out the best way to do this.

The location: my office.

The players: two colleagues from IT, one from finance, myself.

The shared display: Compendium running on my computer, visible to all the players.

The discussion was launched with the issue stated up-front: How should we update our data mart during business hours? My colleagues in the dev team came up with several ideas to address the issue. After capturing the issue and responding ideas, the map looked like this:

Figure 3: Map - stage 1

In brief, the options were to:

- Use our messaging infrastructure to carry out the update.

- Write database triggers on transaction tables. These triggers would update the data mart tables directly or indirectly.

- Write custom T-SQL procedures (or an SSIS package) to carry out the update (the database is SQL Server 2005).

- Run the relevant (already existing) Extract, Transform, Load (ETL) procedures at more frequent intervals – possibly several times during the day.

As the discussion progressed, the developers raised arguments for and against the ideas. A little later the map looked like this:

Figure 4: Map - stage 2

Note that data latency refers to the time interval between when the transaction occurs and its propagation to the data mart, and complexity is a rough measure of the effort required (in time) to implement that option. I won’t go through the arguments in detail, as they are largely self-explanatory.

The business rep then asked how often the ETL could be run.

“The relevant portions can be run hourly, if you really want to,” replied our ETL queen.

“That’s good enough,” said the business rep.

…voilà, we had a solution!

The final map looked much like the previous one: the only additions were the business rep’s question, the developer’s response and a node marking the decision made:

Figure 5: Final Map

Note that a decision node is simply an idea that is accepted (by all parties) as a decision on the issue being discussed.

Admittedly, my little example is nowhere near a complex project. However, before dismissing it outright, consider the following benefits afforded by the process of dialogue mapping:

- Everyone’s point of view was taken into account.

- The shared display served as a focal point of the discussion: the entire group contributed to the development of the map. Further, all points and arguments made were represented in the map.

- The display and discussion around it ensured a common (or shared) understanding of the problem.

- Once a shared understanding was achieved – between the business and IT in this case – the solution was almost obvious.

- The finished map serves as an intuitive summary of the discussion – any participant can go back to it and recall the essential structure of the discussion in a way that’s almost impossible through a written document. If you think that’s a tall claim, here’s a challenge: try reconstructing a meeting from the written minutes.

Enough said, I think.

But perhaps my simple example leaves you unconvinced. If so, I urge you to read Jeff Conklin’s reflections on an “industrial strength” case-study of dialogue mapping. Despite my limited practical experience with the technique, I believe it is an useful way to address issues that arise on complex projects, particularly those involving stakeholders with diverse points of view. That’s not to say that it is a panacea for project complexity – but then, nothing is. From a purely pragmatic perspective, it may be viewed as an addition to a project manager’s tool-chest of communication techniques. For, as I’ve noted elsewhere, “A shared world-view – which includes a common understanding of tools, terminology, culture, politics etc. – is what enables effective communication within a (project) group.” Dialogue mapping provides a practical means to achieve such a shared understanding.