Archive for the ‘Knowledge Management’ Category

Inexplicit knowledge: what people know, but won’t tell

Introduction

Much of the knowledge that exists in organisations remains unarticulated, in the heads of those who work at the coalface of business activities. Knowledge management professionals know this well, and use the terms explicit and tacit knowledge to distinguish between knowledge that can and can’t be communicated via language. Incidentally, the term tacit knowledge was coined by Michael Polanyi – and it is important to note that he used it in a sense that is very different from what it has come to mean in knowledge management. However, that’s a topic for another post. In the present post I look at a related issue that is common in organisations: the fact that much of what people know can be made explicit, but isn’t. Since the discipline of knowledge management is in dire need of more jargon, I call this inexplicit knowledge. To borrow a phrase from Polanyi, inexplicit knowledge is what people know, but won’t tell. Below, I discuss reasons why potentially explicit knowledge remains inexplicit and what can be done about it.

Why inexplicit knowledge is common

Most people would have encountered work situations in which they chose “not to tell” – remaining silent instead of sharing knowledge that would have been helpful. Common reasons for such behaviour include:

- Fear of loss of ownership of the idea: People are attached to their ideas. One reason for not volunteering their ideas is the worry that someone else in the organisation (a peer or manager) might “steal” the idea. Sometimes such behaviour is institutionalised in the form of an “innovation committee” that solicits ideas, offering monetary incentives for those that are deemed the best (more on incentives below). Like most committee-based solutions, this one is a dud. A better option may be to put in place mechanisms to ensure that those who conceive and volunteer ideas are encouraged to see them through to fruition.

- Fear of loss of face and/or fear of reprisals: In organisational cultures that are competitive, people may fear that their ideas will be ridiculed or put down by others. Closely related to this is the fear of reprisals from management. This happens often enough, particularly when the idea challenges the status quo or those in positions of authority. One of the key responsibilities of management is to foster an environment in which people feel psychologically safe to volunteer ideas, however controversial or threatening the ideas may be.

- Lack of incentives: Some people may be willing to part with their ideas, but only at a price. To address this, organisations may offer extrinsic rewards (i.e. material items such as money, gift vouchers etc) for worthwhile ideas. Interestingly, research has shown that non-monetary extrinsic rewards (meals, gifts etc.) are more effective than monetary ones. This makes sense – financial rewards are more easily forgotten; people are more likely to remember a meal at a top-flight restaurant than a 500$ cheque. That said, it is important to note that extrinsic rewards can also lead to unintended side effects. For example, financial incentives based on quantity of contributions might lead to a glut of low-quality contributions. See the next point for a discussion of another side effect of extrinsic rewards.

- Wrong incentives: As I have discussed at length in my post on motivation in knowledge management projects, people will contribute their hard earned knowledge only if they are truly engaged in their work. Such people are intrinsically motivated (i.e. internally motivated, independent of material rewards); their satisfaction comes from their work (yes, such people do exist!). Consequently they need little or no supervision. Intrinsic rewards are invariably non-material and they cannot be controlled by management. A surprising fact is that, intrinsically motivated people can actually be turned off – even offended – by material rewards.

Psychological safety and incentives are important factors, but there is an even more important issue: the relationships between people who make up the workgroup.

Knowledge sharing and the theory of cooperative action

The work of Elinor Ostrom on collective (or cooperative) action is relevant here because knowledge sharing is a form of cooperation. According to the theory of cooperative action, there are three core relationships that promote cooperation in groups: trust, reciprocity and reputation. Below I take a look at each of these in the context of knowledge sharing:

Trust: In the end, whether we choose to share what we know is largely a matter of trust: if we believe that others will respond positively – be it through acknowledgement or encouragement via tangible or intangible rewards – then the chances are that we will tell what we know. On the other hand, if the response is likely to be negative, we may prefer to remain silent.

Reciprocity: This refers to strategies that are based on treating people in the way we believe they would treat us. We are more likely to share what we know with others if we have reason to believe that they would be just as open with us.

Reputation: This refers to the views we have about the individuals we work with. Although such views may be developed by direct observation of peoples’ behaviours, they are also greatly influenced by opinions of others. The relevance of reputation is that we are more likely to be open with people who have a good reputation.

According to Ostrom, these core relationships can be enhanced by face-to-face communication and organisational rules/ norms that promote openness. See my post on Ostrom’s work and its relevance to project management for more on this.

Summing up

One of the key challenges that organisations face is to get people working together in a cooperative manner. Among other things this includes getting people to share their knowledge; to “tell what they know.” Unfortunately, much of this potentially explicit knowledge remains inexplicit, locked away in peoples’ heads, because there is no incentive to share or, even worse, there are factors that actively discourage people from sharing what they know. These issues can be tackled by offering employees the right incentives and creating the right environment. As important as incentives are, the latter is the more important factor: the key to unlocking inexplicit knowledge lies in creating an environment of trust and openness.

On the meaning and interpretation of project documents

Introduction

Most projects generate reams of paperwork ranging from business cases to lessons learned documents. These are usually written with a specific audience in mind: business cases are intended for executive management whereas lessons learned docs are addressed to future project staff (or the portfolio police…). In view of this, such documents are intended to convey a specific message: a business case aims to convince management that a project has strategic value while a lessons learnt document offers future project teams experience-based advice.

Since the writer of a project document has a clear objective in mind, it is natural to expect that the result would be largely unambiguous. In this post, I look at the potential gap between the meaning of a project document (as intended by the author) and its interpretation (by a reader). As we will see, it is far from clear that the two are the same – in fact, most often, they are not. Note that the points I make apply to any kind of written or spoken communication, not just project documents. However, in keeping with the general theme of this blog, my discussion will focus on the latter.

Meaning and truth

Let’s begin with an example. Consider the following statement taken from this sample business case:

“ABC Company has an opportunity to save 260 hours of office labor annually by automating time-consuming and error-prone manual tasks.”

Let’s ask ourselves: what is the meaning of this sentence?

On the face of it, the meaning of a sentence such as the one above is equivalent to knowing the condition(s) under which the claim it makes is true. For example, the statement above implies that if the company undertakes the project (condition) then it will save the stated hours of labour (claim). This interpretation of meaning is called the truth-conditional model. Among other things, it assumes that the truth of a sentence has an objective meaning.

Most people have something like the truth-conditional model in mind when they are writing documents: they (try to) write in a way that makes the truth of their claims plausible or, better yet, evident.

Buehler’s model of language

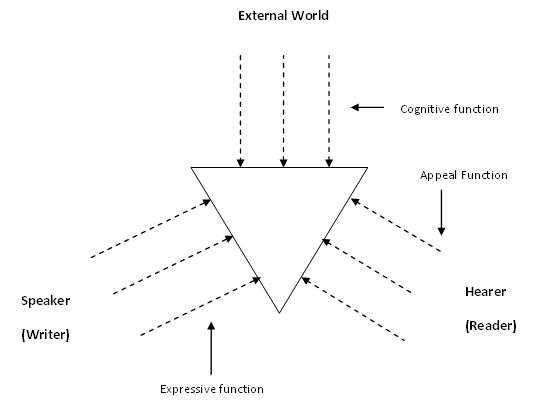

At this point, it is helpful to look at a model of language proposed by the German linguist Karl Buehler in the 1930s. According to Buehler, language has three functions, not just one as in the truth-conditional model. The three functions are:

- Cognitive: representing an (objective) truth about the world. This is the same “truth” as in the truth-conditional model.

- Expressive: expressing a point of view of the writer (or speaker).

- Appeal: making a request of the reader – or “appealing to” the reader.

A graphical representation of the model –sometimes called the organon model – is shown in Figure 1 below.

The basic point Buehler makes is that focusing on the cognitive function alone cannot lead to a complete picture of meaning. One has to factor in the desires and intent of the writer (or speaker) and the predispositions of those who make up the audience. Ultimately, the meaning resides not in some idealized objective truth, but in how readers interpret the document.

Meaning and interpretation

Let’s look at the statement made in the previous section in the light of Buehler’s model.

First, the statement (and indeed the document) makes some claims regarding the external, objective world. This is essentially the same as the truth-conditional view mentioned in the previous section.

Second, from the viewpoint of the expressive function, the statement (and the entire business case, for that matter) selects facts that the writer believes will convince the reader. So, among other things, the writer claims that the company will save 260 hours of manual labour by automating time-consuming and error-prone tasks. The adjectives used imply that some tasks are not carried out efficiently. The author chose to make this point; he or she could have made it another way or even not made it all.

Finally, executives who read the business case might interpret claim made in many different ways depending on:

- Their knowledge of the office environment (things such as the workload of office staff, scope for automation etc.) and the environment. This corresponds to the cognitive function in Buehler’s model.

- Their own predispositions, intentions and desires and those that they impute to the author. This corresponds to the appeal and expressive functions.

For instance, the statement might be viewed as irrelevant by an executive who believes that the existing office staff are perfectly capable of dealing with the workload (“They need to work smarter”, he might say). On the other hand, if he knows that the business case has been written up by the IT department (who are currently looking to justify their budgets), he might well question the validity of the statement and ask for details of how the figure of 260 hours was arrived at. The point is: even a simple and seemingly unambiguous statement (from the point of view of the writer) might be interpreted in a host of unexpected ways.

More than just “sending and receiving”

The standard sender-receiver model of communication is simplistic. Among other things it assumes that interpretation is “just” a matter of interpreting a message correctly. The general assumption is that:

…If the requisite information has been properly packed in a message, only someone who is deficient could fail to get it out. This partitioning of responsibility between the sender and the recipient often results in reciprocal blaming for communication. (Quoted from Questions and Information: contrasting metaphors by Thomas Lauer)

Buehler’s model reminds us that any communication – as clear as it may seem to the sender – is open to being interpreted in a variety of different ways by the receiver. Moreover, the two parties need to understand each others intent and motives, which are generally not open to view.

Wrapping up

The meaning of project documents isn’t as clear-cut as is usually assumed. This is so even for documents that are thought of as being unambiguous (such as contracts or status reports). Writers write from their point of view, which may differ considerably from that of their readers. Further, phrases and sentences which seem clear to a writer can be interpreted in a variety of ways by readers, depending on their situation and motivations. The bottom line is that the writer must not only strive for clarity of expression, but must also try to anticipate ways in which readers might interpret what’s written.

Planning and improvisation – complementary facets of organizational work

Introduction

Cause-effect relationships in the business world are never clear cut. Yet, those who run business organisations hanker after predictability. Consequently, a great deal of effort is expended on planning – thinking out and organizing actions aimed at directing the course of the future. In this “planning view”, time is seen as a commodity that can be divided, allocated and used to achieve organizational aims. In this scheme of things, the future is seen as unfolding linearly, traversing the axis of time according to plan. Although (good) plans factor in uncertainties and unforeseen events, the emphasis is on predictability and it is generally assumed that things will go as foreseen.

In reality things rarely go according to plan. Stuff happens, things that aren’t foreseen – and what’s not foreseen cannot be planned for. People deal with this by improvising, taking extemporaneous actions that feel right at the time. In retrospect such actions often turn out to be right. However, such actions are essentially unplanned; one cannot predict or allocate a particular time at which they will occur. In this sense they lie outside of normal (or planned) organizational time.

In a paper entitled Notes on improvisation and time in organisation (abstract only), Claudio Ciborra considered the nature of improvisation in organisations. Although the paper was written a while ago, primarily as a critique of Business Process Reengineering (BPR) and its negative side effects, many of the points he made are of wider relevance. This post, inspired by Ciborra’s paper, is the first of a two-part series of posts in which I discuss the nature of improvisation and planning in organisations. In the present post I discuss the differences between the two and how they complement each other in practice. In a subsequent post I will talk about how the two lead to different notions of time in organisations.

Contrasting planning and improvisation

The table below summarises some of the key contrasting characteristics between planning and improvisation:

|

Planning |

Improvisation |

| Follows procedures and processes; operates within clearly defined boundaries | Idiosyncratic; boundaries are not well defined, or sometimes not defined at all. |

| Operates within organizational rules and decrees | Often operates outside of organizational rules and norms. |

| Method of solution is assumed to be known. | Method emerges via sensemaking and exploration. |

| Slow, deliberate decision-making | Quick – almost instantaneous decision making |

| Planning attempts to predict and control (how events unfold in) time. | Improvisation is extemporaneous – operates “outside of time” |

In essence improvisation cannot be planned; it is always surprising, even to improvisers.

Planning and improvisation coexist

Following Alfred Schutz, Ciborra notes that in planned work (such as projects) every action is carried out according to a view of a future in which it is already accomplished. In other words, in projects we do things according to a plan because we expect those actions to lead to certain consequences – that is we expect our actions to achieve certain goals. Schutz referred to such motives as in-order-to motives. These motives are embedded in the project and its rationale, and are often documented for all to see. However, in-order-to motives are only part of the story, and a small one at that. More important are the reasons for which the goals are thought to be worthwhile. Among other things, these involve factors relating history, environment and past experiences of the people who make up the organisation or project. Schutz referred to such motivations as because-of motives. These motives are usually tacit and remain so unless a conscious effort is made to surface them.

As Ciborra puts it:

The in-order-to project deals with the actor’s explicit and conscious meaning in solving a problematic situation while the because-of motives can explain why and how a situation has been perceived as problematic in the first place.

The because-of motives are tacit and lie in the background of the explicit project at hand. They fall outside the glance of rational, awake attention during the performance of the action. They could be inferred by an outsider, or made explicit by the actor, but only as a result of reflection after the fact.

(Note that although Ciborra uses the word project as referring to any future-directed action, it could just as well be applied to the kinds of projects you and I work on.)

Ciborra uses the metaphor of an iceberg to illustrate the coexistence of the two types of motives. The in-order-to motives are the tip of the iceberg, there for all to see. On the other hand, because-of motives, though more numerous, are hidden below the surface and can’t be seen unless one makes the effort to see them. Improvisation generally draws upon these tacit, because-of motives that are not visible. Moreover, the very interpretation of formalized procedures and best practices involves these motives. Actions performed as a consequence of such interpretations are what bring procedures and practices to life in specific situations. As Ciborra puts it:

A formalized procedure embeds a set of explicit in-order-to’s, but the way these are actually interpreted and put to work strictly depends upon the actor’s in-order-to and because-of motives, his/her way of being in the world “next” to the procedure, the rule or the plan. In more radical terms what is at stake here is not “objects” or “artifacts” but human existence and experience. Procedure and method are just “dead objects”: they get situated in the flow of organizational life only thanks to a mélange of human motives and actions. One cannot cleanse human existence and experience from the ways of operating and use of artifacts.

In short, planning and improvisation are both necessary for a proper functioning of organizations.

Opposite, but complementary

Planning and improvisation are very different activities – the former is aimed at influencing the future through activities that are pre-organized whereas the latter involves actions that occur just-in-time. Moreover, planning is a result of conscious thought and deliberation whereas improvisation is a result of tacit knowledge being brought to bear, in an instant, on specific situations encountered in project (or other organizational) work. Nevertheless, despite their differences, both activities are important in organizations. Efforts aimed at planning the future down to the last detail are misguided and bound to fail. Contraria sunt complementa: planning and improvisation are opposites, but they are complementary.1

1 The phrase contraria sunt complementa means opposites are complementary. It appears on the physicist Niels Bohr’s coat of arms (he was knighted after he won the Nobel Prize for physics in 1922). Bohr formulated the complementarity principle, the best known manifestation of which is wave-particle duality – i.e. that in the atomic world, particles can display either wave or particle like characteristics, depending on the experimental set up.