Archive for the ‘Knowledge Management’ Category

Capturing decision rationale on projects

Introduction

Most knowledge management efforts on projects focus on capturing what or how rather than why. That is, they focus on documenting approaches and procedures rather than the reasons behind them. This often leads to a situation where folks working on subsequent projects (or even the same project!) are left wondering why a particular technique or approach was favoured over others. How often have you as a project manager asked yourself questions like the following when browsing through a project archive?

- Why did project decision-makers choose to co-develop the system rather than build it in-house or outsource it?

- Why did the developer responsible for a module use this approach rather than that one?

More often than not, project archives are silent on such matters because the reasoning behind decisions isn’t documented. In this post I discuss how the Issue Based Information System (IBIS) notation can be used to fill this “rationale gap” by capturing the reasoning behind project decisions.

Note: Those unfamiliar with IBIS may want to have a browse of my post on entitled what and whence of issue-based information systems for a quick introduction to the notation and its uses. I also recommend downloading and installing Compendium, a free software tool that can be used to create IBIS maps.

Example 1: Build or outsource?

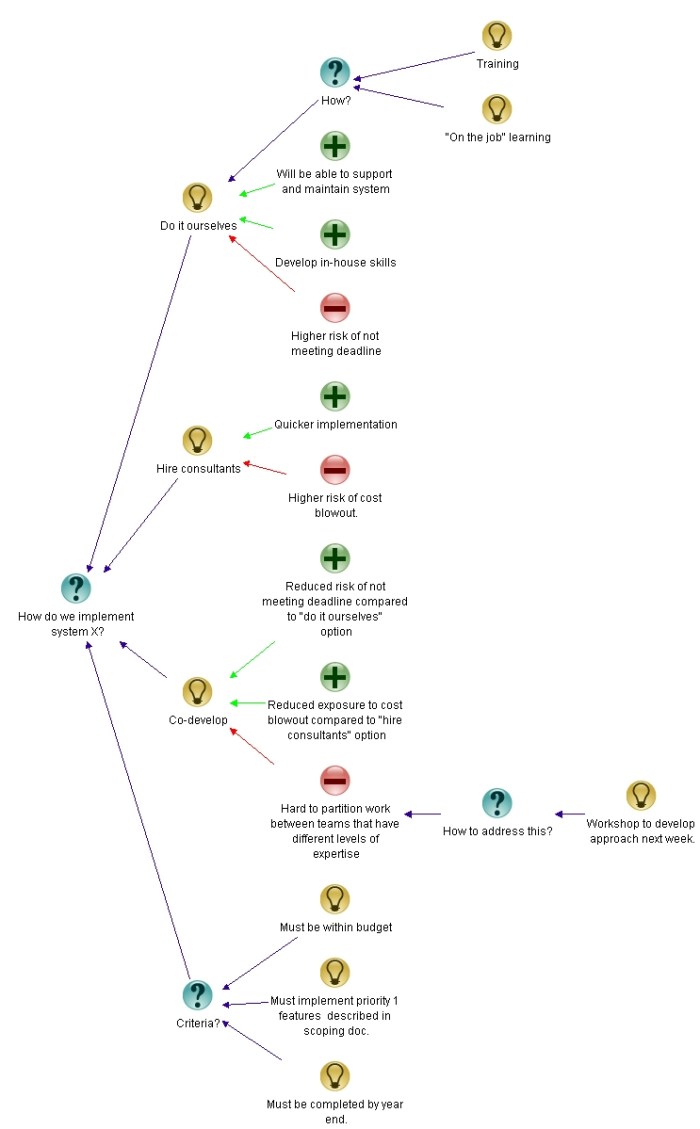

In a post entitled The Approach: A dialogue mapping story, I presented a fictitious account of how a project team member constructed an IBIS map of a project discussion (Note: dialogue mapping refers to the art of mapping conversations as they occur). The issue under discussion was the approach that should be used to build a system.

The options discussed by the team were:

- Build the system in-house.

- Outsource system development.

- Co-develop using a mix of external and internal staff.

Additionally, the selected approach had to satisfy the following criteria:

- Must be within a specified budget.

- Must implement all features that have been marked as top priority.

- Must be completed within a specified time

The post details how the discussion was mapped in real-time. Here I’ll simply show the final map of the discussion (see Figure 1).

Although the option chosen by the group is not marked (they chose to co-develop), the figure describes the pros and cons of each approach (and elaborations of these) in a clear and easy-to-understand manner. In other words, it maps the rationale behind the decision – a person looking at the map can get a sense for why the team chose to co-develop rather than use any of the other approaches.

Example 2: Real-time updates of a data mart

In another post on dialogue mapping I described how IBIS was used to map a technical discussion about the best way to update selected tables in a data mart during business hours. For readers who are unfamiliar with the term: data marts are databases that are (generally) used purely for reporting and analysis. They are typically updated via batch processes that are run outside of normal business hours. The requirement to do real-time updates arose from a business need to see up-to-the-minute reports at specified times during the financial year.

Again, I’ll refer the reader to the post for details, and simply present the final map (see Figure 2).

Since there are a few technical terms involved, here’s a brief rundown of the options, lifted straight from my earlier post (Note: feel free skip this detail – it is incidental to the main point of this post) :

- Use our messaging infrastructure to carry out the update.

- Write database triggers on transaction tables. These triggers would update the data mart tables directly or indirectly.

- Write custom T-SQL procedures (or an SSIS package) to carry out the update (the database is SQL Server 2005).

- Run the relevant (already existing) Extract, Transform, Load (ETL) procedures at more frequent intervals – possibly several times during the day.

In this map the option chosen by the group decision is marked out – it was decided that no additional development was needed; the “real-time” requirement could be satisfied simply by running existing update procedures during business hours (option 4 listed above).

Once again, the reasoning behind the decision is easy to see: the option chosen offered the simplest and quickest way to satisfy the business requirement, even though the update was not really done in real-time.

Summarising

The above examples illustrate how IBIS captures the reasoning behind project decisions. It does so by:

- Making explicit all the options considered.

- Describing the pros and cons of each option (and elaborations thereof).

- Providing a means to explicitly tag an option as a decision.

- Optionally, providing a means to link out to external source (documents, spreadsheets, urls). In the second example I could have added clickable references to documents elaborating on technical detail using the external link capability of Compendium.

Issue maps (as IBIS maps are sometimes called) lay out the reasoning behind decisions in a visual, easy-to-understand way. The visual aspect is important – see this post for more on why visual representations of reasoning are more effective than prose.

I’ve used IBIS to map discussions ranging from project approaches to mathematical model building, and have found them to be invaluable when asked questions about why things were done in a certain way. Just last week, I was able to answer a question about variables used in a market segmentation model that I built almost two years ago – simply by referring back to the issue map of the discussion and the notes I had made in it.

In summary: IBIS provides a means to capture decision rationale in a visual and easy-to-understand way, something that is hard to do using other means.

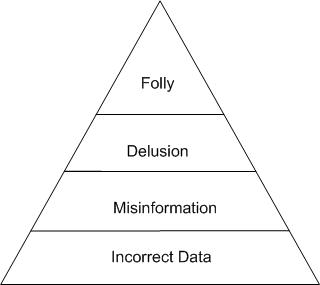

Pathways to folly: a brief foray into non-knowledge

One of the assumptions of managerial practice is that organisational knowledge is based on valid data. Of course, knowledge is more than just data. The steps from data to knowledge and beyond are described in the much used (and misused) data-information-knowledge-wisdom (DIKW) hierarchy. The model organises the aforementioned elements in a “knowledge pyramid” as shown in Figure 1. The basic idea is that data, when organised in a way that makes contextual sense, equates to information which, when understood and assimilated, leads to knowledge which then, finally, after much cogitation and reflection, may lead to wisdom.

In this post, I explore “evil twins” of the DIKW framework: hierarchical models of non-knowledge. My discussion is based on a paper by Jay Bernstein, with some extrapolations of my own. My aim is to illustrate (in a not-so-serious way) that there are many more managerial pathways to ignorance and folly than there are to knowledge and wisdom.

I’ll start with a quote from the paper. Bernstein states that:

Looking at the way DIKW decomposes a sequence of levels surrounding knowledge invites us to wonder if an analogous sequence of stages surrounds ignorance, and where associated phenomena like credulity and misinformation fit.

Accordingly he starts his argument by noting opposites for each term in the DIKW hierarchy. These are listed in the table below:

| DIKW term | Opposite |

| Data | Incorrect data, Falsehood, Missing data, |

| Information | Misinformation, Disinformation, Guesswork, |

| Knowledge | Delusion, Unawareness, Ignorance |

| Wisdom | Folly |

This is not an exhaustive list of antonyms – only a few terms that make sense in the context of an “evil twin” of DIKW are listed. It should also be noted that I have added some antonyms that Bernstein does not mention. In the remainder of this post, I will focus on discussing the possible relationships between these terms that are opposites of those that appear in the DIKW model.

The first thing to note is that there is generally more than one antonym for each element of the DIKW hierarchy. Further, every antonym has a different meaning from others. For example – the absence of data is different from incorrect data which in turn is different from a deliberate falsehood. This is no surprise – it is simply a manifestation of the principle that there are many more ways to get things wrong than there are to get them right.

An implication of the above is that there can be more than one road to folly depending on how one gets things wrong. Before we discuss these, it is best to nail down the meanings of some of the words listed above (in the sense in which they are used in this article):

Misinformation – information that is incorrect or inaccurate

Disinformation – information that is deliberately manipulated to mislead.

Delusion – false belief.

Unawareness – the state of not being fully cognisant of the facts.

Ignorance – a lack of knowledge.

Folly – foolishness, lack of understanding or sense.

The meanings of the other words in the table are clear enough and need no elaboration.

Meanings clarified, we can now look at the some of the “pyramids of folly” that can be constructed from the opposites listed in the table.

Let’s start with incorrect data. Data that is incorrect will mislead, hence resulting in misinformation. Misinformed people end up with false beliefs – i.e. they are deluded. These beliefs can cause them to make foolish decisions that betray a lack of understanding or sense. This gives us the pyramid of delusion shown in Figure 2.

Similarly, Figure 3 shows a pyramid of unawareness that arises from falsehoods and Figure 4, a pyramid of ignorance that results from missing data.

Figures 2 through 4 are distinct pathways to folly. I reckon many of my readers would have seen examples of these in real life situations. (Tragically, many managers who traverse these pathways are unaware that they are doing so. This may be a manifestation of the Dunning-Kruger effect.)

There’s more though – one can get things wrong at higher level independent of whether or not the lower levels are done right. For example, one can draw the wrong conclusions from (correct) data. This would result in the pyramid shown in Figure 5.

Finally, I should mention that it’s even worse: since we are talking about non-knowledge, anything goes. Folly needs no effort whatsoever, it can be achieved without any data, information or knowledge (or their opposites). Indeed, one can play endlessly with antonyms and near-antonyms of the DIKW terms (including those not listed here) and come up with a plethora of pyramids, each denoting a possible pathway to folly.

Why best practices are hard to practice (and what can be done about it)

Introduction

In a recent post entitled, Why Best Practices Are Hard to Practice, Ron Ashkenas mentions two common pitfalls that organisations encounter when implementing best practices. These are:

- Lack of adaptation: this refers to a situation in which best practices are applied without customizing them to an organisation’s specific needs.

- Lack or adoption: this to the tendency of best practice initiatives to fizzle out due to lack of adoption in the day-to-day work of an organisation.

Neither point is new: several practitioners and academics have commented on the importance adaptation and adoption in best practice implementations (see this article from 1997, for example). Despite this, organisations continue to struggle when implementing best practices, which suggests a deeper problem. In this post, I explore the possibility that problems of adaptation and adoption arise because much of the knowledge relevant to best practices is tacit – it cannot be codified or captured via symbolic systems (such as writing) or speech. This “missing” tacit knowledge makes it difficult to adapt and adopt practices in a meaningful way. All is not lost, though: best practices can be useful as long as they are viewed as templates or starting points for discussion, rather than detailed prescriptions that are to be imitated uncritically.

The importance of tacit knowledge

Michael Polanyi’s aphorism – “We can know more than we can tell’ – summarises the difference between explicit and tacit knowledge : the former refers to what we can “tell” (write down, or capture in some symbolic form) whereas the latter are the things we know but cannot explain to others via writing or speech alone.

The key point is: tacit knowledge is more relevant to best practices than its explicit counterpart.

“Why?” I hear you ask.

Short Answer: Explicit knowledge is a commodity that can be bought and sold, tacit knowledge isn’t. Hence it is the latter that gives organisations their unique characteristics and competencies.

For a longer answer, I’ll quote from a highly-cited paper by Maskell and Malmberg entitled, Localised Learning and Industrial Competitiveness:

It is a logical and interesting – though sometimes overlooked – consequence of the present development towards a knowledge-based economy, that the easier codified (tradeable) knowledge is accessed, the more significant becomes tacit knowledge for sustaining the heterogeneity of the firm’s resources. If all factors of production, all organisational blue-prints, all market-information and all production technologies were readily available in all parts of the world at (more or less) the same price, economic progress would dwindle. Resource heterogeneity is the very foundation for building firm specific competencies and thus for variations between firms in their competitiveness. Resource heterogeneity fuels the market process of selection between competing firms

Tacit knowledge thus confers a critical advantage on firms. It is precisely this knowledge that distinguishes firms from each other and sets the “best” (however one might choose to define that) apart from the rest. It is the knowledge that best practices purport to capture, but can’t.

Transferring tacit knowledge

The transfer of tacit knowledge is an iterative and incremental process: apprentices learn by practice, by refining their skills over time. Such learning requires close interaction between the teacher and the taught. Communication technology can obviate the need for some face-to-face interaction but he fact remains that proximity is important for effective transfer of tacit knowledge. In the words of Maskell and Malmberg:

The interactive character of learning processes will in itself introduce geographical space as a necessary dimension to take into account. Modern communications technology will admittedly allow more of long distance interaction than was previously possible. Still, certain types of information and knowledge exchange continue to require regular and direct face-to-face contact. Put simply, the more tacit the knowledge involved, the more important is spatial proximity between the actors taking part in the exchange. The proximity argument is twofold. First, it is related to the time geography of individuals. Everything else being equal, interactive collaboration will be less costly and more smooth, the shorter the distance between the participants. The second dimension is related to proximity in a social and cultural sense. To communicate tacit knowledge will normally require a high degree of mutual trust and understanding, which in turn is related not only to language but also to shared values and ‘culture’.

The main point to take away from their argument is that proximity is important for effective transfer of tacit knowledge. The individuals involved need to be near each other geographically (shared space, face-to-face) and culturally (shared values and norms). By implication, this is also the only way to transfer best practice knowledge.

Discussion

Best practices, by definition, aim to capture knowledge that enables successful organizations be what they are. As we have seen above, much of this knowledge is tacit: it is context and history dependent, and requires physical/cultural proximity for effective transfer. Further, it is hard to extract, codify and transfer such knowledge in a way that makes sense outside its original setting. In light of this, it is easy to understand why adapting and adopting best practices is hard: it is hard because best practices are incomplete – they omit important elements (the tacit bits that can’t be written down). Organisations have to (re)discover these in their own way. The explicit and (re-discovered) tacit elements then need to be integrated into new workplace practices that are necessarily different from standardised best practices. This makes the new practices unique to the implementing organisation.

The above suggests that best practices should be seen as starting points – or “bare bones” templates – for transforming an organisation’s work practices. I have made this point in an earlier post in which I reviewed this paper by Jonathan Wareham and Hans Cerrits. Quoting from that post:

[Wareham and Cerrits] suggest an expanded view of best practices which includes things such as:

- Using best practices as guides for learning new technologies or new ways of working.

- Using best practices to generate creative insight into how business processes work in practice.

- Using best practices as a guide for change – that is, following the high-level steps, but not necessarily the detailed prescriptions.

These are indeed sensible and reasonable statements. However, they are much weaker than the usual hyperbole-laden claims that accompany best practices.

The other important implication of the above is that successful adoption of organisational practices is possible only with the active involvement of front-line employees. “Active” is the operative word here, signifying involvement and participation. One of the best ways to get involvement is to seek and act on employee opinions about their day-to-day work practices. Best practices can serve as templates for these discussions. Participation can be facilitated through the use of collective deliberation techniques such as dialogue mapping.

Wrap-up

Best practices have long been plagued by problems of adaptation and adoption. The basic reason for this is that much of the knowledge pertaining to practices is tacit and cannot be transferred easily. Successful implementation requires that organisations use best practices as templates to build on rather than prescriptions to be followed to the letter. A good way to start this process is through participatory design discussions aimed at filling in the (tacit) gaps. These discussions should be conducted in a way that invites involvement of all relevant stakeholders, especially those who will work with and be responsible for the practices. Such an inclusive approach ensures that the practices will be adapted to suit the organisation’s needs. Further, it improves the odds of adoption because it incorporates the viewpoints of the most important stakeholders at the outset.

Paul Culmsee and I are currently working on a book that describes such an approach that goes “beyond best practices”. See this post for an excerpt from the book (and this one for a rather nice mock-up cover!)