Archive for the ‘Knowledge Management’ Category

Building project knowledge – a social constructivist view

Introduction

Conventional approaches to knowledge management on projects focus on the cognitive (or thought-related) and mechanical aspects of knowledge creation and capture. There is alternate view, one which considers knowledge as being created through interactions between people who – through their interactions – develop mutually acceptable interpretations of theories and facts in ways that suit their particular needs. That is, project knowledge is socially constructed. If this is true, then project managers need to pay attention to the environmental and social factors that influence knowledge construction. This is the position taken by Paul Jackson and Jane Klobas in their paper entitled, Building knowledge in projects: A practical application of social constructivism to information systems development, which presents a knowledge creation / sharing process model based social constructivist theory. This article is a summary and review of the paper.

A social constructivist view of knowledge

Jackson and Klobas begin with the observation that engineering disciplines are founded on the belief that knowledge can be expressed in propositions that correspond to a reality which is independent of human perception. However, there is an alternate view that knowledge is not absolute, but relative – i.e. it depends on the mental models and beliefs used to interpret facts, objects and events. A relevant example is how a software product is viewed by business users and software developers. The former group may see an application in terms of its utility whereas the latter may see it as an instance of a particular technology. Such perception gaps can also occur within seemingly homogenous groups – such as teams comprised of software developers, for example. This can happen for a variety of reasons such as the differences in the experience and cultural backgrounds of those who make up the group. Social constructivism looks at how such gaps can be bridged.

The authors’ discussion relies on the work of Berger and Luckmann, who described how the gap between perceptions of different individuals can be overcome to create a socially constructed, shared reality. The phrase “socially constructed” implies that reality (as it pertains to a project, for example) is created via a common understanding of issues, followed by mutual agreement between all the players as to what comprises that reality. For me this view strikes a particular chord because of it is akin to the stated aims of dialogue mapping, a technique that I have described in several earlier posts (see this article for an example relevant to projects).

Knowledge in information systems development as a social construct

First up, the authors make the point that information systems development (ISD) projects are:

…intensive exercises in constructing social reality through process and data modeling. These models are informed with the particular world-view of systems designers and their use of particular formal representations. In ISD projects, this operational reality is new and explicitly constructed and becomes understood and accepted through negotiated agreement between participants from the two cultures of business and IT

Essentially, knowledge emerges through interaction and discussion as the project proceeds. However, the methodologies used in design are typically founded on an engineering approach, which takes a positivist view rather than a social one. As the authors suggest,

Perhaps the social constructivist paradigm offers an insight into continuing failure, namely that what is happening in an ISD project is far more complex than the simple translation of a description of an external reality into instructions for a computer. It is the emergence and articulation of multiple, indeterminate, sometimes unconscious, sometimes ineffable realities and the negotiated achievement of a consensus of a new, agreed reality in an explicit form, such as a business or data model, which is amenable to computerization.

With this in mind, the authors aim to develop a model that addresses the shortcomings of the traditional, positivist view of knowledge in ISD projects. They do this by representing Berger and Luckmann’s theory of social constructivism in terms of a knowledge process model. They then identify management principles that map on to these processes. These principles form the basis of a survey which is used as an operational version of the process model. The operational model is then assessed by experts and tested by a project manager in a real-life project.

The knowledge creation/sharing process model

The process model that Jackson and Klobas describe is based on Berger and Luckmann’s work.

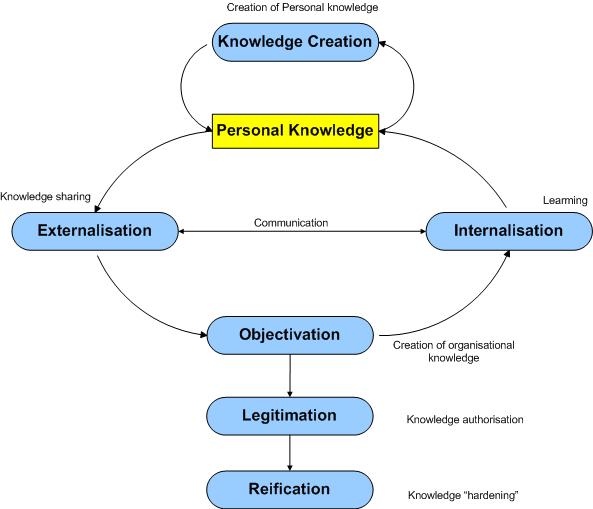

The model describes how personal knowledge is created – personal knowledge being what an individual knows. Personal knowledge is built up using mental models of the world – these models are frameworks that individuals use to make sense of the world.

According to the Jackson-Klobas process model, personal knowledge is built up through a number of process including:

Internalisation: The absorption of knowledge by an individual

Knowledge creation: The construction of new knowledge through repetitive performance of tasks (learning skills) or becoming aware of new ideas, ways of thinking or frameworks. The latter corresponds to learning concepts and theories, or even new ways of perceiving the world. These correspond to a change in subjective reality for the individual.

Externalisation: The representation and description of knowledge using speech or symbols so that it can be perceived and internalized by others. Think of this as explaining ideas or procedures to other individuals.

Objectivation: The creation of a shared constructs that represent a group’s understanding of the world. At this point, knowledge is objectified – and is perceived as having an existence independent of individuals.

Legitimation: The authorization of objectified knowledge as being “correct” or “standard.”

Reification: The process by which objective knowledge assumes a status that makes it difficult to change or challenge. A familiar example of reified knowledge is any procedure or process that is “hardened” into a system – “That’s just the way things are done around here,” is a common response when such processes are challenged.

The links depicted in the figure show the relationships between these processes.

Jackson and Klobas suggest that knowledge creation in ISD projects is a social process, which occurs through continual communication between the business and IT. Sure, there are other elements of knowledge creation – design, prototyping, development, learning new skills etc. – but these amount to nought unless they are discussed, argued, agreed on and communicated through social interactions. These interactions occur in the wider context of the organization, so it is reasonable to claim that the resulting knowledge takes on a form that mirrors the social environment of the organization.

Clearly, this model of knowledge creation is very different from the usual interpretation of knowledge having an independent reality, regardless of whether it is known to the group or not.

An operational model

The above is good theory, which makes for interesting, but academic, discussions. What about practice? Can the model be operationalised? Jackson and Klobas describe an approach to creating to testing the utility (rather than the validity) of the model. I discuss this in the following sections.

Knowledge sharing heuristics

To begin with, they surveyed the literature on knowledge management to identify knowledge sharing heuristics (i.e. experience-based techniques to enable knowledge sharing). As an example, some of the heuristics associated with the externalization process were:

- We have standard documentation and modelling tools which make business requirements easy to understand

- Stakeholders and IS staff communicate regularly through direct face-to-face contact

- We use prototypes

The authors identified more than 130 heuristics. Each of these was matched with a process in the model. According to the authors, this matching process was simple: in most cases there was no doubt as to which process a heuristic should be attached to. This suggests that the model provides a natural way to organize the voluminous and complex body of research in knowledge creation and sharing. Why is this important? Well, because it suggests that the conceptual model (as illustrated in Fig. 1) can form the basis for a simple means to assess knowledge creation / sharing capabilities in their work environments, with the assurance that they have all relevant variables covered.

Validating the mapping

The validity of the matching was checked using twenty historical case studies of ISD projects. This worked as follows: explanations for what worked well and what didn’t were mapped against the model process areas (using the heuristics identified in the prior step). The aim was to answer the question: “is there a relationship between project failure and problems in the respective knowledge processes or, conversely, between project success and the presence of positive indicators?”

One of the case studies the authors use is the well-known (and possibly over-analysed) failure of the automated dispatch system for the London Ambulance Service. The paper has a succinct summary of the case study, which I reproduce below:

The London Ambulance Service (LAS) is the largest ambulance service in the world and provides accident and emergency and patient transport services to a resident population of nearly seven million people. Their ISD project was intended to produce an automated system for the dispatch of ambulances to emergencies. The existing manual system was poor, cumbersome, inefficient and relatively unreliable. The goal of the new system was to provide an efficient command and control process to overcome these deficiencies. Furthermore, the system was seen by management as an opportunity to resolve perceived issues in poor industrial relations, outmoded work practices and low resource utilization. A tender was let for development of system components including computer aided dispatch, automatic vehicle location, radio interfacing and mobile data terminals to update the status of any call-out. The tender was let to a company inexperienced in large systems delivery. Whilst the project had profound implications for work practices, personnel were hardly involved in the design of the system. Upon implementation, there were many errors in the software and infrastructure, which led to critical operational shortcomings such as the failure of calls to reach ambulances. The system lasted only a week before it was necessary to revert to the manual system.

Jackson and Klobas show how their conceptual model maps to knowledge-related factors that may have played a role in the failure project. For example, under the heading of personal knowledge, one can identify at least two potential factors: lack of involvement of end-users in design and selection of an inexperienced vendor. Further, the disconnect between management and employees suggests a couple of factors relating to reification: mutual negative perceptions and outmoded (but unchallenged) work practices.

From their validation, the authors suggest that the model provides a comprehensive framework that explains why these projects failed. That may be overstating the case – what’s cause and what’s effect is hard to tell, especially after the fact. Nonetheless, the model does seem to be able to capture many, if not all, knowledge-related gaps that could have played a role in these failures. Further, by looking at the heuristics mapped to each process, one might be able to suggest ways in which these deficiencies could have been addressed. For example, if externalization is a problem area one might suggest the use of prototypes or encourage face to face communication between IS and business personnel.

Survey-based tool

Encouraged by the above, the authors created a survey tool which was intended to evaluate knowledge creation/sharing effectiveness in project environments. In the tool, academic terms used in the model were translated into everyday language (for example, the term externalization was translated to knowledge sharing – see Fig 1 for translated terms). The tool asked project managers to evaluate their project environments against each knowledge creation process (or capability) on a scale of 1 to 10. Based on inputs, it could recommend specific improvement strategies for capabilities that were scored low. The tool was evaluated by four project managers, who used it in their work environment over a period of 4-6 weeks. At the end of the period, they were interviewed and their responses were analysed using content analysis to match their experiences and requirements against the designed intent of the tool. Unfortunately, the paper does not provide any details about the tool, so it’s difficult to say much more than paraphrase the authors comments.

Based on their evaluation, the authors conclude that the tool provides:

- A common framework for project managers to discuss issues pertaining to knowledge creation and sharing.

- A means to identify potential problems and what might be done to address them.

Field testing

One of the evaluators of the model tested the tool in the field. The tester was a project manager who wanted to identify knowledge creation/sharing deficiencies in his work environment, and ways in which these could be addressed. He answered questions based on his own evaluation of knowledge sharing capabilities in his environment and then developed an improvement plan based on strategies suggested by the tool along with some of his own ideas. The completed survey and plan were returned to the researchers.

Use of the tool revealed the following knowledge creation/sharing deficiencies in the project manager’s environment:

- Inadequate personal knowledge.

- Ineffective externalization

- Inadequate standardization (objectivation)

Strategies suggested by the tool include:

- An internet portal to promote knowledge capture and sharing. This included discussion forums, areas to capture and discuss best practices etc.

- Role playing workshops to reveal how processes worked in practice (i.e. surface tacit knowledge).

Based on the above, the authors suggest that:

- Technology can be used to promote support knowledge sharing and standardization, not just storage.

- Interventions that make tacit knowledge explicit can be helpful.

- As a side benefit, they note that the survey has raised consciousness about knowledge creation/sharing within the team.

Reflections and Conclusions

In my opinion, the value of the paper lies not in the model or the survey tool, but the conceptual framework that underpins them – namely, the idea knowledge depends on, and is shaped by, the social environment in which it evolves. Perhaps an example might help clarify what this means. Consider an organisation that decides to implement project management “best practices” as described by <fill in any of the popular methodologies here>. The wrong way to do this would be to implement practices wholesale, without regard to organizational culture, norms and pre-existing practices. Such an approach is unlikely to lead to the imposed practices taking root in the organisation. On the other hand, an approach that picks the practices that are useful and tailors these to organizational needs, constraints and culture is likely to meet with more success. The second approach works because it attempts to bridge gap between the “ideal best practice” and social reality in the organisation. It encourages employees to adapt practices in ways that make sense in the context of the organization. This invariably involves modifying practices, sometimes substantially, creating new (socially constructed!) knowledge in the bargain.

Another interesting point the authors make is that several knowledge sharing heuristics (130, I think the number was) could be classified unambiguously under one of the processes in the model. This suggests that the model is a reasonable view of the knowledge creation/sharing process. If one accepts this conclusion, then the model does indeed provide a common framework for discussing issues relating knowledge creation in project environments. Further, the associated heuristics can help identify processes that don’t work well.

I’m unable to judge the usefulness of the survey-based tool developed by the authors because they do not provide much detail about it in the paper. However, that isn’t really an issue; the field of project management has too many “tools and techniques” anyway. The key message of the paper, in my opinion, is the that every project has a unique context, and that the techniques used by others have to be interpreted and applied in ways that are meaningful in the context of the particular project. The paper is an excellent counterpoint to the methodology-oriented practice of knowledge management in projects; it should be required reading for methodologists and project managers who believe that things need to be done by The Book, regardless of social or organizational context.

IBIS, dialogue mapping, and the art of collaborative knowledge creation

Introduction

In earlier posts I’ve described a notation called IBIS (Issue-based information system), and demonstrated its utility in visualising reasoning and resolving complex issues through dialogue mapping. The IBIS notation consists of just three elements (issues, ideas and arguments) that can be connected in a small number of ways. Yet, despite these limitations, IBIS has been found to enhance creativity when used in collaborative design discussions. Given the simplicity of the notation and grammar, this claim is surprising, even paradoxical. The present post resolves this paradox by viewing collaborative knowledge creation as an art, and considers the aesthetic competencies required to facilitate this art.

Knowledge art

In a position paper entitled, The paradox of the “practice level” in collaborative design rationale, Al Selvin draws an analogy between design discussions using Compendium (an open source IBIS-based argument mapping tool) and art. He uses the example of the artist Piet Mondrian, highlighting the difference in style between Mondrian’s earlier and later work. To quote from the paper,

Whenever I think of surfacing design rationale as an intentional activity — something that people engaged in some effort decide to do (or have to do), I think of Piet Mondrian’s approach to painting in his later years. During this time, he departed from the naturalistic and impressionist (and more derivative, less original) work of his youth (view an image here) and produced the highly abstract geometric paintings (view an image here) most associated with his name…

Selvin points out that the difference between the first and the second paintings is essentially one of abstraction: the first one is almost instantly recognisable as a depiction of dunes on a beach whereas the second one, from Mondrian’s minimalist period, needs some effort to understand and appreciate, as it uses a very small number of elements to create a specific ambience. To quote from the paper again,

“One might think (as many in his day did) that he was betraying beauty, nature, and emotion by going in such an abstract direction. But for Mondrian it was the opposite. Each of his paintings in this vein was a fresh attempt to go as far as he could in the depiction of cosmic tensions and balances. Each mattered to him in a deeply personal way. Each was a unique foray into a depth of expression where nothing was given and everything had to be struggled for to bring into being without collapsing into imbalance and irrelevance. The depictions and the act of depicting were inseparable. We get to look at the seemingly effortless result, but there are storms behind the polished surfaces. Bringing about these perfected abstractions required emotion, expression, struggle, inspiration, failure and recovery — in short, creativity…”

In analogy, Selvin contends that a group of people who work through design issues using a minimalist notation such as IBIS can generate creative new ideas. In other words: IBIS, when used in a group setting such as dialogue mapping, can become a vehicle for collaborative creativity. The effectiveness of the tool, though, depends on those who wield it:

“…To my mind using tools and methods with groups is a matter of how effective, artistic, creative, etc. whoever is applying and organizing the approach can be with the situation, constraints, and people. Done effectively, even the force-fitting of rationale surfacing into a “free-flowing” design discussion can unleash creativity and imagination in the people engaged in the effort, getting people to “think different” and look at their situation through a different set of lenses. Done ineffectively, it can impede or smother creativity as so many normal methods, interventions, and attitudes do…”

Although Selvin’s discussion is framed in the context of design discussions using Compendium, this is but dialogue mapping by another name. So, in essence, he makes a case for viewing the collaborative generation of knowledge (through dialogue mapping or any other means) as an art. In fact, in another article, Selvin uses the term knowledge art to describe both the process and the product of creating knowledge as discussed above. Knowledge Art as he sees it, is a marriage of the two forms of discourse that make up the term. On the one hand, we have knowledge which, “… in an organizational setting, can be thought of as what is needed to perform work; the tacit and explicit concepts, relationships, and rules that allow us to know how to do what we do.” On the other, we have art which “… is concerned with heightened expression, metaphor, crafting, emotion, nuance, creativity, meaning, purpose, beauty, rhythm, timbre, tone, immediacy, and connection.”

Facilitating collaborative knowledge creation

In the business world, there’s never enough time to deliberate or think through ideas (either individually or collectively): everything is done in a hurry and the result is never as good as it should or could be; the picture never quite complete. However, as Selvin says,

“…each moment (spent discussing or thinking through ideas or designs) can yield a bit of the picture, if there is a way to capture the bits and relate them, piece them together over time. That capturing and piecing is the domain of Knowledge Art. Knowledge Art requires a spectrum of skills, regardless of how it’ practiced or what form it takes. It means listening and paying attention, determining the style and level of intervention, authenticity, engagement, providing conceptual frameworks and structures, improvisation, representational skill and fluidity, and skill in working with electronic information…”

So, knowledge art requires a wide range of technical and non-technical skills. In previous posts I’ve discussed some of technical skills required – fluency with IBIS, for example. Let’s now look at some of the non-technical competencies.

What are the competencies needed for collaborative knowledge creation? Palus and Horth offer some suggestions in their paper entitled, Leading Complexity; The Art of Making Sense. They define the concept of creative leadership as making shared sense out of complexity and chaos and the crafting of meaningful action. Creative leadership is akin to dialogue mapping, which Jeff Conklin describes as a means to achieve a shared understanding of wicked problems and a shared commitment to solving them. The connection between creative leadership and dialogue mapping is apparent once one notices the similarity between their definitions. So the competencies of creative leadership should apply to dialogue mapping (or collaborative knowledge creation) as well.

Palus and Horth describe six basic competencies of creative leadership. I outline these below, mentioning their relevance to dialogue mapping:

Paying Attention: This refers to the ability to slow down discourse with the aim of achieving a deep understanding of the issues at hand. A skilled dialogue mapper has to be able to listen; to pay attention to what’s being said.

Personalizing: This refers to the ability to draw upon personal experiences, interests and passions whilst engaged in work. Although the connection to dialogue mapping isn’t immediately evident, the point Palus and Horth make is that the ability to make connections between work and one’s interests and passions helps increase involvement, enthusiasm and motivation in tackling work challenges.

Imaging: This refers to the ability to visualise problems so as to understand them better, using metaphors, pictures stories etc to stimulate imagination, intuition and understanding. The connection to dialogue mapping is clear and needs no elaboration.

Serious play: This refers to the ability to experiment with new ideas; to learn by trying and doing in a non-threatening environment. This is something that software developers do when learning new technologies. A group engaged in a dialogue mapping must have a sense of play; of trying out new ideas, even if they seem somewhat unusual.

Collaborative enquiry: This refers to the ability to sustain productive dialogue in a diverse group of stakeholders. Again, the connection to dialogue mapping is evident.

Crafting: This refers to the ability to synthesise issues, ideas, arguments and actions into coherent, meaningful wholes. Yet again, the connection to dialogue mapping is clear – the end product is ideally a shared understanding of the problem and a shared commitment to a meaningful solution.

Palus and Horth suggest that these competencies have been ignored in the business world because:

- They are seen as threatening the status quo (creativity is to feared because it invariably leads to changes).

- These competencies are aesthetic, and the current emphasis on scientific management devalues competencies that are not rational or analytical.

The irony is that creative scientists have these aesthetic competencies (or qualities) in spades. At the most fundamental level science is an art – it is about constructing theories or designing experiments that make sense of the world. Where do the ideas for these new theories or experiments come from? Well, they certainly aren’t out there in the objective world; they come from the imagination of the scientist. Science, in the real sense of the word, is knowledge art. If these competencies are useful in science, they should be more than good enough for the business world.

Summing up

To sum up: knowledge creation in an organisational context is best viewed as an art – a collaborative art. Visual representations such as IBIS provide a medium to capture snippets of knowledge and relate them, or piece them together over time. They provide the canvas, brush and paint to express knowledge as art through the process of dialogue mapping.

The what and whence of issue-based information systems

Over the last few months I’ve written a number of posts on IBIS (short for Issue Based Information System), an argument visualisation technique invented in the early 1970s by Horst Rittel and Werner Kunz. IBIS is best known for its use in dialogue mapping – a collaborative approach to tackling wicked problems – but it has a range of other applications as well (capturing project knowledge is a good example). All my prior posts on IBIS focused on its use in specific applications. Hence the present piece, in which I discuss the “what” and “whence” of IBIS: its practical aspects – notation, grammar etc. – along with its origins, advantages and limitations

I’ll begin with a brief introduction to the technique (in its present form) and then move on to its origins and other aspects.

A brief introduction to IBIS

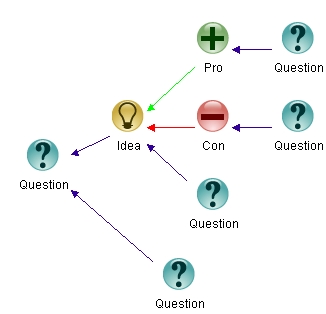

IBIS consists of three main elements:

- Issues (or questions): these are issues that need to be addressed.

- Positions (or ideas): these are responses to questions. Typically the set of ideas that respond to an issue represents the spectrum of perspectives on the issue.

- Arguments: these can be Pros (arguments supporting) or Cons (arguments against) an issue. The complete set of arguments that respond to an idea represents the multiplicity of viewpoints on it.

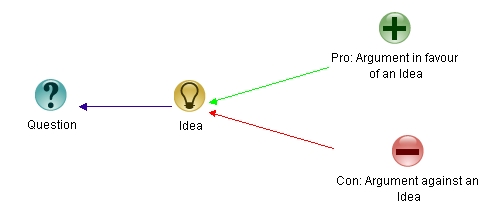

The best IBIS mapping tool is Compendium – it can be downloaded here. In Compendium, the IBIS elements described above are represented as nodes as shown in Figure 1: issues are represented by green question nodes; positions by yellow light bulbs; pros by green + signs and cons by red – signs. Compendium supports a few other node types, but these are not part of the core IBIS notation. Nodes can be linked only in ways specified by the IBIS grammar as I discuss next.

Figure 1: IBIS Elements

The IBIS grammar can be summarized in a few simple rules:

- Issues can be raised anew or can arise from other issues, positions or arguments. In other words, any IBIS element can be questioned. In Compendium notation: a question node can connect to any other IBIS node.

- Ideas can only respond to questions – i.e. in Compendium “light bulb” nodes can only link to question nodes. The arrow pointing from the idea to the question depicts the “responds to” relationship.

- Arguments can only be associated with ideas – i.e in Compendium + and – nodes can only link to “light bulb” nodes (with arrows pointing to the latter)

The legal links are summarized in Figure 2 below.

The rules are best illustrated by example- follow the links below to see some illustrations of IBIS in action:

- See this post for a simple example of dialogue mapping.

- See this post or this one for examples of argument visualisation .

- See this post for the use IBIS in capturing project knowledge.

Now that we know how IBIS works and have seen a few examples of it in action, it’s time to trace its history from its origins to the present day.

Wicked origins

A good place to start is where it all started. IBIS was first described in a paper entitled, Issues as elements of Information Systems; written by Horst Rittel (who coined the term “wicked problem”) and Werner Kunz in July 1970. They state the intent behind IBIS in the very first line of the abstract of their paper:

Issue-Based Information Systems (IBIS) are meant to support coordination and planning of political decision processes. IBIS guides the identification, structuring, and settling of issues raised by problem-solving groups, and provides information pertinent to the discourse.

Rittel’s preoccupation was the area of public policy and planning – which is also the context in which he defined wicked problems originally. He defined the term in his landmark paper of 1973 entitled, Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning. A footnote to the paper states that it is based on an article that he presented at an AAAS meeting in 1969. So it is clear that he had already formulated his ideas on wickedness when he wrote his paper on IBIS in 1970.

Given the above background it is no surprise that Rittel and Kunz foresaw IBIS to be the:

…type of information system meant to support the work of cooperatives like governmental or administrative agencies or committees, planning groups, etc., that are confronted with a problem complex in order to arrive at a plan for decision…

The problems tackled by such cooperatives are paradigm-defining examples of wicked problems. From the start, then, IBIS was intended as a tool to facilitate a collaborative approach to solving such problems.

Operation of early systems

When Rittel and Kunz wrote their paper, there were three IBIS-type systems in operation: two in governmental agencies (in the US, one presumes) and one in a university environment (possibly, Berkeley, where Rittel worked). Although it seems quaint and old-fashioned now, it is no surprise that they were all manual, paper-based systems- the effort and expense involved in computerizing such systems in the early 70s would have been prohibitive, and the pay-off questionable.

The paper also offers a short description of how these early IBIS systems operated:

An initially unstructured problem area or topic denotes the task named by a “trigger phrase” (“Urban Renewal in Baltimore,” “The War,” “Tax Reform”). About this topic and its subtopics a discourse develops. Issues are brought up and disputed because different positions (Rittel’s word for ideas or responses) are assumed. Arguments are constructed in defense of or against the different positions until the issue is settled by convincing the opponents or decided by a formal decision procedure. Frequently questions of fact are directed to experts or fed into a documentation system. Answers obtained can be questioned and turned into issues. Through this counterplay of questioning and arguing, the participants form and exert their judgments incessantly, developing more structured pictures of the problem and its solutions. It is not possible to separate “understanding the problem” as a phase from “information” or “solution” since every formulation of the problem is also a statement about a potential solution.

Even today, forty years later, this is an excellent description of how IBIS is used to facilitate a common understanding of complex (or wicked) problems. The paper contains an overview of the structure and operation of manual IBIS-type systems. However, I’ll omit these because they are of little relevance in the present-day world.

As an aside, there’s a term that’s conspicuous by its absence in the Rittel-Kunz paper: design rationale. Rittel must have been aware of the utility of IBIS in capturing design rationale: he was a professor of design science at Berkley and design reasoning was one of his main interests. So it is somewhat odd that he does not mention this term even once in his IBIS paper.

Fast forward a couple decades (and more!)

In a paper published in 1988 entitled, gIBIS: A hypertext tool for exploratory policy discussion, Conklin and Begeman describe a prototype of a graphical, hypertext-based IBIS-type system (called gIBIS) and its use in capturing design rationale (yes, despite the title of the paper, it is more about capturing design rationale than policy discussions). The development of gIBIS represents a key step between the original Rittel-Kunz version of IBIS and its present-day version as implemented in Compendium. Amongst other things, IBIS was finally off paper and on to disk, opening up a new world of possibilities.

gIBIS aimed to offer users:

- The ability to capture design rationale – the options discussed (including the ones rejected) and the discussion around the pros and cons of each.

- A platform for promoting computer-mediated collaborative design work – ideally in situations where participants were located at sites remote from each other.

- The ability to store a large amount of information and to be able to navigate through it in an intuitive way.

Before moving on, one point needs to be emphasized: gIBIS was intended to be used in collaborative settings; to help groups achieve a shared understanding of central issues, by mapping out dialogues in real time. In present-day terms – one could say that it was intended as a tool for sense making.

The gIBIS prototype proved successful enough to catalyse the development of Questmap, a commercially available software tool that supported IBIS. However, although there were some notable early successes in the real-time use of IBIS in industry environments (see this paper, for example), these were not accompanied by widespread adoption of the technique. Other graphical, IBIS-like methods to capture design rationale were proposed (an example is Questions, Options and Criteria (QOC) proposed by MacLean et. al. in 1991), but these too met with a general reluctance in adoption.

Making sense through IBIS

The reasons for the lack of traction of IBIS-type techniques in industry are discussed in an excellent paper by Shum et. al. entitled, Hypermedia Support for Argumentation-Based Rationale: 15 Years on from gIBIS and QOC. The reasons they give are:

- For acceptance, any system must offer immediate value to the person who is using it. Quoting from the paper, “No designer can be expected to altruistically enter quality design rationale solely for the possible benefit of a possibly unknown person at an unknown point in the future for an unknown task. There must be immediate value.” Such immediate value is not obvious to novice users of IBIS-type systems.

- There is some effort involved in gaining fluency in the use of IBIS-based software tools. It is only after this that users can gain an appreciation of the value of such tools in overcoming the limitations of mapping design arguments on paper, whiteboards etc.

The intellectual effort – or cognitive overhead, as it is called in academese – in using IBIS in real time involves:

- Teasing out issues, ideas and arguments from the dialogue.

- Classifying points raised into issues, ideas and arguments.

- Naming (or describing) the point succinctly.

- Relating (or linking) the point to an existing node.

This is a fair bit of work, so it is no surprise that beginners might find it hard to use IBIS to map dialogues. However, once learnt, a skilled practitioner can add value to design (and more generally, sense making) discussions in several ways including:

- Keeping the map (and discussion) coherent and focused on pertinent issues.

- Ensuring that all participants are engaged in contributing to the map (and hence the discussion).

- Facilitating useful maps (and dialogues) – usefulness being measured by the extent to which the objectives of the session are achieved.

See this paper by Selvin and Shum for more on these criteria. Incidentally, these criteria are a qualitative measure of how well a group achieves a shared understanding of the problem under discussion. Clearly, there is a good deal of effort involved in learning and becoming proficient at using IBIS-type systems, but the payoff is an ability to facilitate a shared understanding of wicked problems – whether in public planning or in technical design.

Why IBIS is better than conventional modes of documentation

IBIS has several advantages over conventional documentation systems. Rittel and Kunz’s 1970 paper contains a nice summary of the advantages, which I paraphrase below:

- IBIS can bridge the gap between discussions and records of discussions (minutes, audio/video transcriptions etc,). IBIS sits between the two, acting as a short term memory. The paper thus foreshadows the use of issue-based systems as an aid to organizational or project memory.

- Many elements (issue, ideas or arguments) that come up in a discussion have contextual meanings that are different from any pre-existing definitions. In discussions, contextual meaning is more than formal meaning. IBIS captures the former in a very clear way – for example a response to a question “What do we mean by X? elicits the meaning of X in the context of the discussion, which is then subsequently captured as an idea (position)”.

- Related to the above, the commonality of an issue with other, similar issues might be more important than its precise meaning. To quote from the paper, “…the description of the subject matter in terms of librarians or documentalists (sic) may be less significant than the similarity of an issue with issues dealt with previously and the information used in their treatment…” With search technologies available, this is less of an issue now. However, search technologies are still limited in terms of finding matches between “similar” items (How is “similar” defined? Ans: it depends on context). A properly structured, context-searchable IBIS-based project archive may still be more useful than a conventional document archive based on a document management system.

- The reasoning used in discussions is made transparent, as is the supporting (or opposing) evidence. (see my post on visualizing argumentation for example)

- The state of the argument (discussion) at any time can be inferred at a glance (unlike the case in written records). See this post for more on the advantages of visual documentation over prose.

Issues with issue-based information systems

Lest I leave readers with the impression that IBIS is a panacea, I should emphasise that it isn’t. According to Conklin, IBIS maps have the following limitations:

- They atomize streams of thought into unnaturally small chunks of information thereby breaking up any smooth rhetorical flow that creates larger, more meaningful chunks of narrative.

- They disperse rhetorically connected chunks throughout a large structure.

- They are not is not chronological in structure (the chronological sequence is normally factored out);

- Contributions are not attributed (who said what is normally factored out).

- They do not convey the maturity of the map – one cannot distinguish, from the map alone, whether one map is more “sound” than another.

- They do not offer a systematic way to decide if two questions are the same, or how the maps of two related questions relate.

Some of these issues (points 3, 4) can be addressed by annotating nodes; others are not so easy to solve.

Concluding remarks

My aim in this post has been to introduce readers to the IBIS notation, and also discuss its origins, development and limitations. On one hand, a knowledge of the origins and development is valuable because it gives insight into the rationale behind the technique, which leads to a better understanding of the different ways in which it can be used. On the other, it is also important to know a technique’s limitations, if for no other reason than to be aware of these so that one can work around them.

Before signing off, I’d like to mention an observation from my experience with IBIS. The real surprise for me has been that the technique can capture most written arguments and discussions, despite having only three distinct elements and a very simple grammar. Yes, it does require some thought to do this, particularly when mapping discussions in real time. However, this cognitive “overhead” is good because it forces the mapper to think about what’s being said instead of just writing it down blind. Thoughtful transcription is the aim of the game. When done right, this results in a map that truly reflects a shared understanding of the complex (and possibly wicked) problem under discussion.

There’s no better coda to this post on IBIS than the following quote from this paper by Conklin:

…Despite concerns over the years that IBIS is too simple and limited on the one hand or too hard to use on the other, there is a growing international community who are fluent enough in IBIS to facilitate and capture highly contentious debates using dialogue mapping, primarily in corporate and educational environments…

For me that’s reason enough to improve my understanding of IBIS and its applications, and to look for opportunities to use it in ever more challenging situations.