Archive for the ‘mismanagement’ Category

Planned failure – a project management paradox

The other day a friend and I were talking about a failed process improvement initiative in his organisation. The project had blown its budget and exceeded the allocated time by over 50%, which in itself was a problem. However, what I found more interesting was that the failure was in a sense planned – that is, given the way the initiative was structured, failure was almost inevitable. Consider the following:

- Process owners had little or no input into the project plan. The “plan” was created by management and handed down to those at the coalface of processes. This made sense from management’s point of view – they had an audit deadline to meet. However, it alienated those involved from the outset.

- The focus was on time, cost and scope; history was ignored. Legacy matters – as Paul Culmsee mentions in a recent post, “To me, considering time, cost and scope without legacy is delusional and plain dumb. Legacy informs time, cost and scope and challenges us to look beyond the visible symptoms of what we perceive as the problem to what’s really going on.” This is an insightful observation – indeed, ignoring legacy is guaranteed to cause problems down the line.

The conversation with my friend got me thinking about planned failures in general. A feature that is common to many failed projects is that planning decisions are based on dubious assumptions. Consider, for example, the following (rather common) assumptions made in project work:

- Stakeholders have a shared understanding of project goals. That is, all those who matter are on the same page regarding the expected outcome of the project.

- Key personnel will be available when needed and – more importantly – will be able to dedicate 100% of their committed time to the project.

The first assumption may be moot because stakeholders view a project in terms of their priorities and these may not coincide with those of other stakeholder groups. Hence the mismatch of expectations between, say, development and marketing groups in product development companies. The second assumption is problematic because key project personnel are often assigned more work than they can actually do. Interestingly, this happens because of flawed organisational procedures rather than poor project planning or scheduling – see my post on the resource allocation syndrome for a detailed discussion of this issue.

Another factor that contributes to failure is that these and other such assumptions often come in to play during the early stages of a project. Decisions that are based on these assumptions thus affect all subsequent stages of the project. To make matters worse, their effects can be amplified as the project progresses. I have discussed these and other problems in my post on front-end decision making in projects.

What is relevant from the point of view of failure is that assumptions such as the ones above are rarely queried, which begs the question as to why they remain unchallenged. There are many reasons for this, some of the more common ones are:

- Groupthink: This is the tendency of members of a group to think alike because of peer pressure and insulation from external opinions. Project groups are prone to falling into this trap, particularly when they are under pressure. See this post for more on groupthink in project environments and ways to address it.

- Cognitive bias: This term refers to a wide variety of errors in perception or judgement that humans often make (see this Wikipedia article for a comprehensive list of cognitive biases). In contrast to groupthink, cognitive bias operates at the level of an individual. A common example of cognitive bias at work in projects is when people underestimate the effort involved in a project task through a combination of anchoring and/or over-optimism (see this post for a detailed discussion of these biases at work in a project situation). Further examples can be found in in my post on the role of cognitive biases in project failure, which discusses how many high profile project failures can be attributed to systematic errors in perception and judgement.

- Fear of challenging authority: Those who manage and work on projects are often reluctant to challenge assumptions made by those in positions of authority. As a result, they play along until the inevitable train wreck occurs.

So there is no paradox: planned failures occur for reasons that we know and understand. However, knowledge is one thing, acting on it quite another. The paradox will live on because in real life it is not so easy to bell the cat.

Pathways to folly: a brief foray into non-knowledge

One of the assumptions of managerial practice is that organisational knowledge is based on valid data. Of course, knowledge is more than just data. The steps from data to knowledge and beyond are described in the much used (and misused) data-information-knowledge-wisdom (DIKW) hierarchy. The model organises the aforementioned elements in a “knowledge pyramid” as shown in Figure 1. The basic idea is that data, when organised in a way that makes contextual sense, equates to information which, when understood and assimilated, leads to knowledge which then, finally, after much cogitation and reflection, may lead to wisdom.

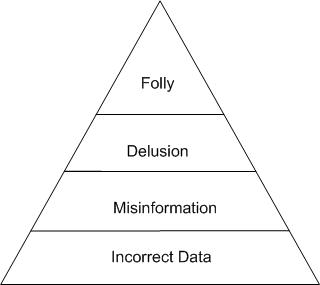

In this post, I explore “evil twins” of the DIKW framework: hierarchical models of non-knowledge. My discussion is based on a paper by Jay Bernstein, with some extrapolations of my own. My aim is to illustrate (in a not-so-serious way) that there are many more managerial pathways to ignorance and folly than there are to knowledge and wisdom.

I’ll start with a quote from the paper. Bernstein states that:

Looking at the way DIKW decomposes a sequence of levels surrounding knowledge invites us to wonder if an analogous sequence of stages surrounds ignorance, and where associated phenomena like credulity and misinformation fit.

Accordingly he starts his argument by noting opposites for each term in the DIKW hierarchy. These are listed in the table below:

| DIKW term | Opposite |

| Data | Incorrect data, Falsehood, Missing data, |

| Information | Misinformation, Disinformation, Guesswork, |

| Knowledge | Delusion, Unawareness, Ignorance |

| Wisdom | Folly |

This is not an exhaustive list of antonyms – only a few terms that make sense in the context of an “evil twin” of DIKW are listed. It should also be noted that I have added some antonyms that Bernstein does not mention. In the remainder of this post, I will focus on discussing the possible relationships between these terms that are opposites of those that appear in the DIKW model.

The first thing to note is that there is generally more than one antonym for each element of the DIKW hierarchy. Further, every antonym has a different meaning from others. For example – the absence of data is different from incorrect data which in turn is different from a deliberate falsehood. This is no surprise – it is simply a manifestation of the principle that there are many more ways to get things wrong than there are to get them right.

An implication of the above is that there can be more than one road to folly depending on how one gets things wrong. Before we discuss these, it is best to nail down the meanings of some of the words listed above (in the sense in which they are used in this article):

Misinformation – information that is incorrect or inaccurate

Disinformation – information that is deliberately manipulated to mislead.

Delusion – false belief.

Unawareness – the state of not being fully cognisant of the facts.

Ignorance – a lack of knowledge.

Folly – foolishness, lack of understanding or sense.

The meanings of the other words in the table are clear enough and need no elaboration.

Meanings clarified, we can now look at the some of the “pyramids of folly” that can be constructed from the opposites listed in the table.

Let’s start with incorrect data. Data that is incorrect will mislead, hence resulting in misinformation. Misinformed people end up with false beliefs – i.e. they are deluded. These beliefs can cause them to make foolish decisions that betray a lack of understanding or sense. This gives us the pyramid of delusion shown in Figure 2.

Similarly, Figure 3 shows a pyramid of unawareness that arises from falsehoods and Figure 4, a pyramid of ignorance that results from missing data.

Figures 2 through 4 are distinct pathways to folly. I reckon many of my readers would have seen examples of these in real life situations. (Tragically, many managers who traverse these pathways are unaware that they are doing so. This may be a manifestation of the Dunning-Kruger effect.)

There’s more though – one can get things wrong at higher level independent of whether or not the lower levels are done right. For example, one can draw the wrong conclusions from (correct) data. This would result in the pyramid shown in Figure 5.

Finally, I should mention that it’s even worse: since we are talking about non-knowledge, anything goes. Folly needs no effort whatsoever, it can be achieved without any data, information or knowledge (or their opposites). Indeed, one can play endlessly with antonyms and near-antonyms of the DIKW terms (including those not listed here) and come up with a plethora of pyramids, each denoting a possible pathway to folly.

Elephants in the room: seven reasons why project risks are ignored

Project managers know from experience that projects can go wrong because of events that weren’t foreseen. Some of these may be unforeseeable– that is, they could not have been anticipated given what was known prior to their occurrence. On the other hand it is surprisingly common that known risks are ignored. The metaphor of the elephant in the room is appropriate here because these risks are quite obvious to outsiders, but apparently not to those involved in the project. This is a strange state of affairs because:

- Those involved in the project are best placed to “see the elephant”

- They are directly affected when the elephant goes on rampage – i.e. the risk eventuates.

This post discusses reasons why these metaphorical pachyderms are ignored by those who need most to recognize their existence .

Let’s get right into it then – seven reasons why risks are ignored on projects:

1. Let sleeping elephants lie: This is a situation in which stakeholders are aware of the risk, but don’t do anything about it in the hope that it will not eventuate. Consequently, they have no idea how to handle it if it does. Unfortunately, as Murphy assures us, sleeping elephants will wake at the most inconvenient moment.

2. It’s not my elephant: This is a situation where no one is willing to take responsibility for managing the risk. This game of “pass the elephant” is resolved by handing charge of the elephant to a reluctant mahout.

3. Deny the elephant’s existence: This often manifests itself as a case of collective (and wilful) blindness to obvious risks. No one acknowledges the risk, perhaps out of fear of that they will be handed responsibility for it (see point 2 above).

4. The elephant has powerful friends: This is a pathological situation where some stakeholders (often those with clout) actually increase the likelihood of a risk through bad decisions. A common example of this is the imposition of arbitrary deadlines, based on fantasy rather than fact.

5. The elephant might get up and walk away: This is wishful thinking, where the team assumes that the risk will magically disappear. This is the “hope and pray” method of risk management, quite common in some circles.

6. The elephant’s not an elephant: This is a situation where a risk is mistaken for an opportunity. Yes, this does happen. An example is when a new technology is used on a project: some team members may see it as an opportunity, but in reality it may pose a risk.

7. The elephant’s dead: This is exemplified by the response, “that is no longer a problem,” when asked about the status of a risk. The danger in these situations is that the elephant may only be fast asleep, not dead.

Risks that are ignored are the metaphorical pachyderms in the room. Ignoring them is easy because it involves no effort whatsoever. However, it is a strategy that is fraught with danger because once these risks eventuate, they can – like those apparently invisible elephants – run amok and wreak havoc on projects.

(Image courtesy John Atkinson: https://wronghands1.com/2018/01/12/parts-of-the-elephant-in-the-room/)