Archive for the ‘Project Management’ Category

Rituals in information system design and development

Introduction

Information system development is generally viewed as a rational process involving steps such as planning, requirements gathering, design etc. However, since it often involves many people, it is only natural that the process will have social and political dimensions as well.

The rational elements of the development process focus on matters such as analysis, coding and adherence to guidelines etc. On the other hand, the socio-political aspects are about things such as differences of opinion, conflict, organisational turf wars etc. The interesting thing, however, is that elements that appear to be rational are sometimes subverted to achieve political ends. Shorn of their original intent, they become rituals that are performed for symbolic reasons rather than rational ones. In this paper I discuss rituals in system development, drawing on a paper by Daniel Robey and Lynne Markus entitled, Rituals in Information System Design .

Background

According to the authors, labelling the process of system design and development as rational implies that the process can be set out and explained in a logical way. Moreover, it also implies that the system being designed has clear goals that can be defined upfront, and that the implemented system will be used in the manner intended by the designers. On the other hand, a political perspective would emphasise the differences between various stakeholder groups (e.g. users, sponsors and developers) and how each group uses the process in ways that benefit them, sometimes to the detriment of others.

In the paper the authors discuss how the following two elements of the system development process are consistent with both views summarised above.

- System development lifecycle.

- Techniques for user involvement

I’ll look at each of these in turn in the next two sections, emphasising their rational features.

Development lifecycle

The basic steps of a system development lifecycle, common to all methodologies, are:

- Inception

- Requirements gathering / analysis

- Specification

- Design

- Programming

- Testing

- Training

- Rollout

Waterfall methodologies run through each of the above once whereas Iterative/Incremental methods loop through (a subset of) them as many times as needed.

It is easy to see that the lifecycle has a rational basis – specification depends on requirements and can therefore be done only after requirements have been gathered and analysis; programming can only proceed after design in completed, and so on It all sounds very logical and rational. Moreover, for most mid-size or large teams, each of the above activities is carried out by different individuals – business analysts, architects/designers, programmers, testers, trainers and operations staff. So the advantage of following a formal development cycle is that it makes it easier to plan and coordinate large development efforts, at least in principle.

Techniques for user involvement

It is a truism that the success of a system depends critically on the level of user interest and engagement it generates. User involvement in different phases of system development is therefore seen as a key to generating and maintaining user engagement. Some of the common techniques to solicit user involvement include:

- Requirements analysis: Direct interaction with users is necessary in order to get a good understanding of their expectations from the system. Another benefit is that it gives the project team an early opportunity to gain user engagement.

- Steering committees: Typically such committees are composed of key stakeholders from each group that is affected by the system. Although some question the utility of steering committees, it is true that committees that consist of high ranking executives can help in driving user engagement.

- Prototyping: This involves creating a working model that serves to demonstrate a subset of the full functionality of the system. The great advantage of this method of user involvement that it gives users an opportunity to provide feedback early in the development lifecycle.

Again, it is easy to see that the above techniques have a rational basis: the logic being that involving users early in the development process helps them become familiar with the system, thus improving the chances that they will be willing, even enthusiastic adopters of the system when it is rolled out.

The political players

Politics is inevitable in any social system that has stakeholder groups with differing interests. In the case of system development, two important stakeholder groups are users and developers. Among other things, the two groups differ in:

- Cognitive style: developers tend to be analytical/logical types while users come from a broad spectrum of cognitive types. Yes, this is a generalisation, but it is largely true.

- Position in organisation: in a corporate environment, business users generally outrank technical staff.

- Affiliations: users and developers belong to different organisational units and therefore have differing loyalties.

- Incentives: Typically member of the two groups have different goals. The developers may be measured by the success of the rollout whereas users may be judged by their proficiency on the new system and the resulting gains in productivity.

These lead to differences in ways the two groups perceive processes or events. For example, a developer may see a specification as a blueprint for design whereas a user might see it as a bureaucratic document that locks them into choices they are ill equipped to make. Such differences in perceptions make it far from obvious that the different parties can converge on a common worldview that is assumed by the rational perspective. Indeed, in such situations it isn’t clear at all as to what constitutes “common interest.” Indeed, it is such differences that lead to the ritualisation of aspects of the systems development process.

Ritualisation of rational processes

We now look at how the differences in perspectives can lead to a situation where processes that are intended to be rational end up becoming rituals.

Let’s begin with an example that occurs at the inception phase of system development project: the formulation of a business case. The stated intent of a business case is to make a rational argument as to why a particular system should be built. Ideally it should be created jointly by the business and technology departments. In practice, however, it frequently happens that one of the two parties is given primary responsibility for it. As the two parties are not equally represented, the business case ends up becoming a political document: instead of presenting a balanced case, it presents a distorted view that focuses on one party’s needs. When this happens, the business case becomes symbol rather than substance – in other words, a ritual.

Another example is the handover process between developers and users (or operations, for that matter). The process is intended to ensure that the system does indeed function as promised in the scope document. Sometimes though, both parties attempt to safeguard their own interests: developers may pressure users to sign off whereas users may delay signing-off because they want to check the system ever more thoroughly. In such situations the handover process serves as a forum for both parties to argue their positions rather than as a means to move the project to a close. Once again, the actual process is shorn of its original intent and meaning, and is thus ritualised.

Even steering committees can end up being ritualised. For example, when a committee consists of senior executives from different divisions, it can happen that each member will attempt to safeguard the interests of his or her fief. Committee meetings then become forums to bicker rather than to provide direction to the project. In other words, they become symbolic events that achieve little of substance.

Discussion

The main conclusion from the above argument is that information system design and implementation is both a rational and political process. As a consequence, many of the processes associated with it turn out to be more like rituals in that they symbolise rationality but are not actually rational at all.

That said, it should be noted that rituals have an important function: they serve to give the whole process of systems development a veneer of rationality whilst allowing for the political manouevering that is inevitable in large projects. As the authors put it:

Rituals in systems development function to maintain the appearance of rationality in systems development and in organisational decision making. Regardless of whether it actually produces rational outcomes or not, systems development must symbolize rationality and signify that the actions taken are not arbitrary but rather acceptable within the organisation’s ideology. As such, rituals help provide meaning to the actions taken within an organisation

And I feel compelled to add: even if the actions taken are completely irrational and arbitrary…

Summary…and a speculation

In my experience, the central message of the paper rings true: systems development and design, like many other organisational processes and procedures, are often hijacked by different parties to suit their own ends. In such situations, processes are reduced to rituals that maintain a facade of rationality whilst providing cover for politicking and other not-so-rational actions.

Finally, it is interesting to note that the problem of ritualisation is a rather general one: many allegedly rational processes in organisations are more symbol than substance. Examples of other processes that are prone to ritualisation include performance management, project management and planning. This hints at a deeper issue, one that I think has its origins in modern management’s penchant for overly prescriptive, formulaic approaches to managing organisations and initiatives. That, however, remains a speculation and a topic for another time…

On the inherent ambiguities of managing projects

Much of mainstream project management is technique-based – i.e. it is based on processes that are aimed at achieving well-defined ends. Indeed, the best-known guide in the PM world, the PMBOK, is structured as a collection of processes and associated “tools and techniques” that are categorised into various “knowledge areas.”

Yet, as experienced project managers know, there is more to project management than processes and techniques: success often depends on a project manager’s ability to figure out what to do in unique situations. Dealing with such situations is more an art rather than science. This process (if one can call it that) is difficult to formalize and even harder to teach. As Donald Schon wrote in a paper on the crisis of professional knowledge :

…the artistic processes by which practitioners sometimes make sense of unique cases, and the art they sometimes bring to everyday practice, do not meet the prevailing criteria of rigorous practice. Often, when a competent practitioner recognizes in a maze of symptoms the pattern of a disease, constructs a basis for coherent design in the peculiarities of a building site, or discerns an understandable structure in a jumble of materials, he does something for which he cannot give a complete or even a reasonably accurate description. Practitioners make judgments of quality for which they cannot state adequate criteria, display skills for which they cannot describe procedures or rules.

Unfortunately this kind of ambiguity is given virtually no consideration in standard courses on project management. Instead, like most technically-oriented professions such as engineering, project management treats problems as being well-defined and amenable to standard techniques and solutions. Yet, as Schon tells us:

…the most urgent and intractable issues of professional practice are those of problem-finding. “Our interest”, as one participant put it, “is not only how to pour concrete for the highway, but what highway to build? When it comes to designing a ship, the question we have to ask is, which ship makes sense in terms of the problems of transportation?

Indeed, the difficulty in messy project management scenarios often lies in figuring out what to do rather than how to do it. Consider the following situations:

- You have to make an important project-related decision, but don’t have enough information to make it.

- Your team is overworked and your manager has already turned down a request for more people.

- A key consultant on your project has resigned.

Each of the above is a not-uncommon scenario in the world of projects. The problem in each of these cases lies in figuring out what to do given the unique context of the project. Mainstream project management offers little advice on how to deal with such situations, but their ubiquity suggests that they are worthy of attention.

In reality, most project managers deal with such situations using a mix of common sense, experience and instinct, together with a deep appreciation of the specifics of the environment (i.e. the context). Often times their actions may be in complete contradiction to textbook techniques. For example, in the first case described above, the rational thing to do is to gather more data before making a decision. However, when faced with such a situation, a project manager might make a snap decision based on his or her knowledge of the politics of the situation. Often times the project manager will not be able to adequately explain the rationale for the decision beyond knowing that “it felt like the right thing to do.” It is more an improvisation than a plan.

Schon used the term reflection-in-action to describe how practitioners deal with such situations, and used the following example to illustrate how it works in practice:

Recently, for example, I built a wooden gate. The gate was made of wooden pickets and strapping. I had made a drawing of it, and figured out the dimensions I wanted, but I had not reckoned with the problem of keeping the structure square. I noticed, as I began to nail the strapping to the pickets that the whole thing wobbled. I knew that when I nailed in a diagonal piece, the structure would become rigid. But how would I be sure that, at that moment, the structure would be square? I stopped to think. There came to mind a vague memory about diagonals-that in a square, the diagonals are equal. I took a yard stick, intending to measure the diagonals, but I found it difficult to make these measurements without disturbing the structure. It occurred to me to use a piece of string. Then it became apparent that I needed precise locations from which to measure the diagonal from corner to corner. After several frustrating trials, I decided to locate the center point at each of the corners (by crossing diagonals at each corner), hammered in a nail at each of the four center points, and used the nails as anchors for the measurement string. It took several moments to figure out how to adjust the structure so as to correct the errors I found by measuring, and when I had the diagonal equal, I nailed in the piece of strapping that made the structure rigid…

Such encounters with improvisation are often followed by a retrospective analysis of why the actions taken worked (or didn’t). Schoen called this latter process reflection-on-action. I think it isn’t a stretch to say that project managers hone their craft through reflection in and on ambiguous situations. This knowledge cannot be easily codified into techniques or practices but is worthy of study in its own right. To this end, Schon advocated an epistemology of (artistic) practice – a study of what such knowledge is and how it is acquired. In his words:

…the study of professional artistry is of critical importance. We should be turning the puzzle of professional knowledge on its head, not seeking only to build up a science applicable to practice but also to reflect on the reflection-in-action already embedded in competent practice. We should be exploring, for example, how the on-the-spot experimentation carried out by practicing architects, physicians, engineers and managers is like, and unlike, the controlled experimentation of laboratory scientists. We should be analyzing the ways in which skilled practitioners build up repertoires of exemplars, images and strategies of description in terms of which they learn to see novel, one-of-a-kind phenomena. We should be attentive to differences in the framing of problematic situations and to the rare episodes of frame-reflective discourse in which practitioners sometimes coordinate and transform their conflicting ways of making sense of confusing predicaments. We should investigate the conventions and notations through which practitioners create virtual worlds-as diverse as sketch-pads, simulations, role-plays and rehearsals-in which they are able to slow down the pace of action, go back and try again, and reduce the cost and risk of experimentation. In such explorations as these, grounded in collaborative reflection on everyday artistry, we will be pursuing the description of a new epistemology of practice.

It isn’t hard to see that similar considerations hold for project management and related disciplines.

In closing, project management as laid out in books and BOKs does not equip a project manager to deal with ambiguity. As a start towards redressing this, formal frameworks need to acknowledge the limitations of the techniques and procedures they espouse. Although there is no simple, one-size-fits-all way to deal with ambiguity in projects, lumping it into a bucket called “risk” (or worse, pretending it does not exist) is not the answer.

Organisational surprise and its relevance to project management

Introduction

As humans, we tend to believe that events and processes will unfold in the way we expect them to. Unfortunately things rarely go according to our expectations and we end up being, well… surprised! But it isn’t just individuals, entire organisations can be caught unawares by events. In this post I draw on a paper entitled, Clues, Cues and Complexity: Unpacking the Concept of Organisational Surprise, to elaborate on the different ways in which surprises can crop up in organisational settings and in particular, in projects. My focus is on the latter because the temporary and one-off nature of projects seems to render them particularly prone to surprises.

Organizational surprise

The authors define organizational surprise as, “any event that happens unexpectedly or any expected event that takes an unexpected shape.” One does not have to look far to see examples of organizational surprises. It is almost certain that any experienced project manager would have encountered a number of surprises in the course of his or her professional work. These could be unforeseen events (such as a project sponsor leaving for greener pastures) or unexpected twists and turns in what ought to have been a straightforward process (such as a software upgrade turning out to be more complicated than expected).

The ubiquity of organizational surprises begs the question as to why we are still “surprised by surprises.” The short answer is that this happens because we tend to overestimate our ability to control the future. The authors suggest that we would be better served by regarding surprise as an inherent property of all open systems (which includes entities such as organisations and projects). After living through the consequences of many over-optimistic managerial actions (both, my own and those of others), I would have to agree.

Classifying surprise – a typology of surprises

Nothing I have said so far would be surprising to readers: indeed, project management is largely about managing uncertainty…and all project managers know that. What might be new, however, is a classification of surprises proposed by the authors of the paper. I have hinted at the classification in the previous section where I gave one example each of a surprising event and a surprising process. It is now time to generalize this to a typology of surprises.

The authors classify surprises along two dimensions:

- Issue – An issue can occur in one of two ways:

- When something unusual happens.

- When something that usually happens does not happen.

It is important to note that although the term issue has negative connotations in project management parlance, it is used here in a neutral sense – i.e. issues can be either positive or negative.

- Process – a process is a chain of related events that unfolds in an unusual manner. For example, when an ATM cash withdrawal fails because the machine does not have enough money left to process the withdrawal.

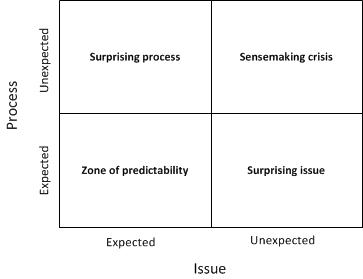

From the perspective of surprise, issues and processes can be either expected or unexpected. This gives us the four categories illustrated in Fig 1.

Let’s take a tour of the four categories

- Expected issue and process: This is the zone of predictability where one-off events tend to go as foreseen. An example of an expected issue that was successfully dealt with through planning was the Y2K problem. Another example is provided by (successful) risk management activities that are triggered when a foreseen risk eventuates.

- Unexpected issue, expected process: This is where a surprising issue occurs, but the consequences follow are expected. An example this would be a chance occurrence (say, a project team member on a troubled project stumbles on a novel technique that saves development time), and this leads to the project being completed within time and budget (expected process following the event).

- Expected issue, unexpected process: This occurs when an expected event evolves in an unexpected way – i.e. leads to a surprising process. A common example of this in a project environment is when a front-end project decision unfolds in unexpected ways. Another common example is an organizational change that has unintended consequences.

- Unexpected issue, unexpected process: This is a situation where both the event and the processes around it are counter to conventional wisdom. In this case, those involved need to understand, or make sense of the situation and hence the term sensemaking crisis. An example of this is when project managers fail to anticipate factors that turn out to have a major influence on the way their projects evolve. One could argue that many high profile project failures were the result of such crises. The Denver Baggage Handling System and the Merck Vioxx affair are good examples. In both cases, the projects failed because those responsible failed to react to certain events that changed the trajectory of the projects irrevocably.

Let’s now take a brief look at the usefulness of this classification.

Coping with surprise

Managers expend a great deal of effort in attempting to predict surprises and hence corral them into the zone of predictability (Reminder: this is the bottom left quadrant in Figure 1). As mentioned earlier, this is difficult because organisations are open systems, and novelty is an inherent property of such systems. The main implication of this is that surprises in quadrants other than the zone of predictability cannot be foreseen. So, instead of worrying about predicting surprises, project and program managers would do better by focusing their efforts on creating an environment that enables team members to cope with nasty surprises and take advantage of good ones.

What might such an environment look like?

This question is best approached via a related question: what are the qualities displayed by project teams that are able to cope with surprises?

Here are some essential ones that are mentioned in the paper:

- Vigilance / problem sensing– a deep awareness of the project environment, with the ability to sense any changes in it.

- Resilience – the capacity to adjust to changes in the internal and external environment.

- Ability to improvise– the ability to respond to the unexpected by devising appropriate courses of action under pressure

The striking thing about these qualities is that they are impossible to create or engender by management fiat: teams will not improvise unless they feel empowered to, nor will they be resilient or vigilant unless they are intrinsically motivated to be so.These characteristics are emergent in the sense that they will be displayed spontaneously by teams that are in a frame of mind that comes out of being in the right environment.

The primary task of a project manager, or any manager for that matter, is to create such a holding environment that provides psychological safety to the team and encourages rational (or open) dialogue between all project stakeholders (yes, including project sponsors). I won’t elaborate on these terms here since they are dealt with at length in the articles that I have provided links to in the previous sentence.

Different types of surprise require different approaches

Having the right environment is the key to dealing with all four kinds of surprises. However, even within such an environment, it is important to note that different types of surprises have to be tackled in different ways. In particular:

- Predictable surprises are best tackled through traditional management approaches (as discussed in PMBOK, for example). In view of the prevalence of such approaches, I should perhaps emphasise again that they work only for a small subset of all possible surprises (only those that lie in the first quadrant)

- Surprising events and surprising processes are best dealt with by the people who are at the coalface of the problem since they are intimately familiar with the context and history of the problem.

- Sensemaking crises are best handled by collaborative problem solving approaches such as Dialogue Mapping.

The above yet again underscores the importance of the creating the right environment, for although predictable surprises can be tackled through traditional approaches to project management, those that lie in the other three quadrants cannot.

Conclusion

A fact of organizational life is that project managers are often caught unawares by unforeseen events and their dynamics. In this post, I have summarized a typology of organizational surprises and have elaborated on its relevance to project management. I have also briefly discussed the ways in which different types of surprises can be tackled, emphasising that the key to tackling surprise lies in creating an environment that provides psychological safety and encourages open dialogue.

In closing, I reiterate that projects and organisations are open systems, and surprises are characteristic of such systems. The biggest surprise, therefore, is that we are continually surprised by some of the events and processes that occur within them