Archive for the ‘Understanding AI’ Category

Analogy, relevance realisation and the limits of AI

The falling price and increasing pervasiveness of LLM-based AIs make it easy to fall for the temptation to outsource one’s thinking to machines. Indeed, much of the noise from vendors is aimed at convincing you to do just that. To be sure, there is little harm and some benefit in using AI to assist with drudgework (e.g. minuting meetings) providing one ensures that the output is validated (e.g., Are the minutes accurate? Have nuances been captured? Have off-the-record items been redacted?). However, as the complexity of the task increases, there comes a point where only those with domain expertise can use AIs as assistants effectively.

This is unsurprising to those who know that the usefulness of AI output depends critically on both the quality of the prompt and the ability to assess its output. But it is equally unsurprising that vendors will overstate claims about their products’ capabilities and understate the knowledge and experience required to use them well.

Over the last year or so, a number of challenging benchmarks have been conquered by so-called Large Reasoning Models. This begs the question as to whether there are any inherent limitations to the kinds of cognitive tasks that LLM-based AIs are capable of. At this time it is not possible to answer this question definitively, but one can get a sense for the kinds of tasks that would be challenging for machines by analysing examples of high-quality human thinking.

In a previous article, I described two examples highlighting the central role that analogies play in creative scientific work. My aim in the present piece is to make the case that humans will continue to be better than machines at analogical thinking, at least for the foreseeable future.

–x–

The two analogies I described in my previous article are:

- Newton’s intuition that the fall of an apple on the surface of the earth is analogous to the motion of the moon in its orbit. This enabled him to develop arguments that led to the Universal Law of Gravitation.

- Einstein’s assumption that the energy associated with electromagnetic radiation is absorbed or emitted in discrete packets akin to particles. This enabled him to make an analogy between electromagnetic radiation and an ideal gas, leading to a heuristic justification for the existence of photons (particles of light).

AI evangelists will point to papers that demonstrate analogical reasoning in LLMs (see this paper for example). However, most of these works suggest that AIs are nowhere near as good as humans in analogising. Enthusiasts may then argue that it’s a matter of time before AI catches up. I do not think this will happen because there are no objective criteria by which one can judge an analogy to be logically sound. Indeed, as I discuss below, analogies have to be assessed in terms of relevance rather than truth.

–x–

The logical inconsistency of analogical reasoning is best illustrated by an example drawn from a paper by Gregory Bateson in which he compares the following two syllogisms:

All humans are mortal (premise)

Socrates is human (premise)

Therefore, Socrates is mortal (conclusion)

and

Humans die

Grass dies

Humans are grass

The first syllogism is logically sound because it infers something about a particular member of a set from a statement that applies to all members of that set. The second is unsound because it compares members of different sets based on a shared characteristic – it is akin, for example, to saying mud (member of one set) is chocolate (member of another set) because they are both brown (shared characteristic).

The syllogism in grass, as Bateson called it, is but analogy by another name. Though logically incorrect, syllogisms can give rise to fruitful trains of thought. For example, Bateson’s analogy draws our attention to the fact that both humans and grass are living organisms subject to evolution. This might then lead to thoughts on the co-dependency of grass and humans – e.g. the propagation of grass via the creation of lawns for aesthetic purposes.

Though logically and scientifically unsound, syllogisms in grass can motivate new lines thinking. Indeed, Newton’s apple and Einstein’s photon are analogies akin to Bateson’s syllogism in grass.

–x–

The moment of analogical insight is one of seeing connections between apparently unconnected phenomena. This is a process of sensemaking – i.e. one of taking or framing a problem from a given situation. To do this effectively, one must first understand what aspects of the situation are significant, a process that is called relevance realisation.

In a recent paper, Johannes Jaeger and his colleagues note that living organisms exists in a continual flux of information most of which is irrelevant to their purposes. From this information deluge they must recognise the miniscule fraction of signals or cues that might inform their actions. However, as they note,

“Before they can infer (or decide on) anything, living beings must first turn ill-defined problems into well-defined ones, transform large worlds into small, translate intangible semantics into formalized syntax (defined as the rule-based processing of symbols free of contingent, vague, and ambiguous external referents). And they must do this incessantly: it is a defining feature of their mode of existence.”

This process, which living creatures engage in continually, is the central feature of relevance realisation. Again, quoting from the paper,

“…it is correct to say that “to live is to know” [Editor’s note: a quote taken from this paper by Maturana https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03033910.1988.10557705]. At the very heart of this process is the ability to pick out what is relevant — to delimit an arena in a large world. This is not a formalizable or algorithmic process. It is the process of formalizing the world in Hilbert’s sense of turning ill-defined problems into well-defined ones.”

The process of coming up with useful analogies is, at its heart, a matter of relevance realisation.

–x–

The above may seem far removed from Newton’s apple and Einstein’s photon, but it really isn’t. The fact that Einstein’s bold hypothesis took almost twenty years to be accepted despite strong experimental evidence supporting it suggests that the process of relevance realisation in science is a highly subjective, individual matter. It is only through a (often long) process of socialisation and consensus building that “facts” and “theories” become objective. As Einstein stated in a lecture at UCLA in the 1930s:

“Science as something already in existence, already completed, is the most objective, impersonal thing that we humans know. Science as something coming into being, as a goal, is just as subjectively, psychologically conditioned as are all other human endeavours.”

That is, although established scientific facts are (eventually seen as being) objective, the process by which they are initially formulated depends very much on subjective choices made by an individual scientist. Such choices are initially justified via heuristic or analogical (rather than logical) arguments which draw on commonalities between disparate objects or phenomena. Out of an infinity of possible analogies, the scientist picks one that is most relevant to the problem at hand. And as Jaeger and co have argued, this process of relevance realisation cannot be formalised.

–x–

To conclude: unlike humans, LLMs and AIs in general, are incapable of relevance realisation. So, although LLMs might come up with creative analogies by the thousands, they cannot use them to enhance our understanding of the world. Indeed, good analogies – like those of Newton and Einstein – do not so much solve problems as disclose new ways of knowing. They are examples of intellectual entrepreneurship, a uniquely human activity that machines cannot emulate.

–x–x–

Towards a public understanding of AI – notes from an introductory class for a general audience

There is a dearth of courses for the general public on AI. To address this gap, I ran a 3-hour course entitled “AI – A General Introduction” on November 4th at the Workers Education Association (WEA) office in Sydney. My intention was to introduce attendees to modern AI via a historical and cultural route, from its mystic 13th century origins to the present day. In this article I describe the content of the session, offering some pointers for those who would like to run similar courses.

–x–

First some general remarks about the session:

- The course was sold out well ahead of time – there is clearly demand for such offerings.

- Although many attendees had used ChatGPT or other similar products, none had much of an idea of how they worked or what they are good (and not so good) for.

- The session was very interactive with lots of questions. Attendees were particularly concerned about social implications of AI (job losses, medical applications, regulation).

- Most attendees did not have a technical background. However, judging from their questions and feedback, it seems that most of them were able to follow the material.

The biggest challenge in designing a course for the public is the question of prior knowledge – what one can reasonably assume the audience already knows. When asked this question, my contact at WEA said I could safely assume that most attendees would have a reasonable familiarity with western literature, history and even some philosophy, but would be less au fait with science and tech. Based on this, I decided to frame my course as a historical / cultural introduction to AI.

–x–

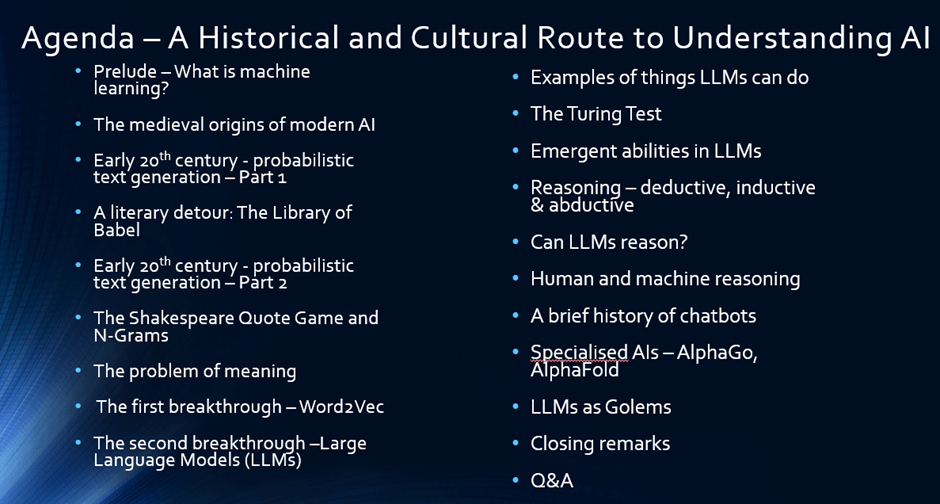

The screenshot below, taken from my slide pack, shows the outline of the course

Here is a walkthrough the agenda, with notes and links to sources:

- I start with a brief introduction to machine learning, drawing largely on the first section of this post.

- The historical sections, which are scattered across the agenda (see figure above), are based on this six part series on the history of natural language processing (NLP) supplemented by material from other sources.

- The history starts with the Jewish mystic Abraham Abulafia and his quest for divine incantations by combining various sacred words. I also introduce the myth of the golem as a metaphor for the double-edgedness of technology, mentioning that I will revisit it at the end of the lecture in the context of AI ethics.

- To introduce the idea of text generation, I use the naïve approach of generating text by randomly combining symbols (alphabet, basic punctuation and spaces), and then demonstrate the futility of this approach using Jorge Luis Borges famous short story, The Library of Babel.

- This naturally leads to more principled approaches based on the actual occurrence of words in text. Here I discuss the pioneering work of Markov and Shannon.

- I then use a “Shakespeare Quote Game” to illustrate the ideas behind next word completion using n-grams. I start with the first word of a Shakespeare quote and ask the audience to guess the quote. With just one word, it is difficult to figure out. However, as I give them more and more consecutive words, the quote becomes more apparent.

- I then illustrate the limitations of n-grams by pointing out the problem of meaning – specifically, the issues associated with synonymy and polysemy. This naturally leads on to Word2Vec, which I describe by illustrating the key idea of how rolling context windows over large corpuses leads to a resolution of the problem. The basic idea here is that instead of defining the meaning of words, we simply consider multiple contexts in which they occur. If done over large and diverse corpuses, this approach can lead to an implicit “understanding” of the meanings of words.

- I also explain the ideas behind word embeddings and vectors using a simple 3d example. Then using vectors, I provide illustrative examples of how the word2vec algorithm captures grammatical and semantic relationships (e.g., country/capital and comparative-superlative forms).

- From word2vec, I segue to transformers and Large Language Models (LLMs) using a hand-wavy discussion. The point here is not so much the algorithm, but how it is (in many ways) a logical extension of the ideas used in early word embedding models. Here I draw heavily on Stephen Wolfram’s excellent essay on ChatGPT.

- I then provide some examples of “good” uses of LLMs – specifically for ideation, explanation and a couple of examples of how I use it in my teaching.

- Any AI course pitched to a general audience must deal with the question of intelligence – what it is, how to determine whether a machine is intelligent etc. To do this, I draw on Alan Turing’s 1950 paper in which he proposes his eponymous test. I illustrate how well LLMs do on the test and ask the question – does this mean LLMs are intelligent? This provokes some debate.

- Instead of answering the question, I suggest that it might be more worthwhile to see if LLMs can display behaviours that one would expect from intelligent beings – for example, the ability to combine different skills or to solve puzzles / math problems using reasoning (see this post for examples of these). Before dealing with the latter, I provide a brief introduction to deductive, inductive and abductive reasoning using examples from popular literature.

- I leave the question of whether LLMs can reason or not unanswered, but I point to a number of different approaches that are popularly used to demonstrate reasoning capabilities of LLMs – e.g. chain of thought prompting. I also make the point that the response obtained from LLMs is heavily dependent on the prompt, and that in many ways, an LLM’s response is a reflection of the intelligence of the user, a point made very nicely by Terrence Sejnowski in this paper.

- The question of whether LLMs can reason is also related to whether we humans think in language. I point out that recent research suggests that we use language to communicate our thinking, but not to think (more on this point here). This poses an interesting question which Cormac McCarthy explored in this article.

- I follow this with a short history of chatbots starting from Eliza to Tay and then to ChatGPT. This material is a bit out of sequence, but I could not find a better place to put it. My discussion draws on the IEEE history mentioned at the start of this section complemented with other sources.

- For completeness, I discuss a couple of specialised AIs – specifically AlphaFold and AlphaGo. My discussion of AlphaFold starts with a brief explanation of the protein folding problem and its significance. I then explain how AlphaFold solved this problem. For AlphaGo, I briefly describe the game of Go, why its considered far more challenging than chess. This is followed by high level explanation of how AlphaGo works. I close this section with a recommendation to watch the brilliant AlphaGo documentary.

- To close, I loop back to where I started – the age old human fascination with creating machines in our own image. The golem myth has a long history which some scholars have traced back to the bible. Today we are a step closer to achieving what medieval mystics yearned for, but it seems we don’t quite know how to deal with the consequences.

I sign off with some open questions around ethics and regulation – areas that are still wide open – as well as some speculations on what comes next, emphasising that I have no crystal ball!

–x–

A couple of points to close this piece.

There was a particularly interesting question from an attendee about whether AI can help solve some of the thorny dilemmas humankind faces today. My response was that these challenges are socially complex – i.e., different groups see these problems differently – so they lack a commonly agreed framing. Consequently, AI is unlikely to be of much help in addressing these challenges. For more on dealing with socially complex or ambiguous problems, see this post and the paper it is based on.

Finally, I’m sure some readers may be wondering how well this approach works. Here are some excerpts from emails I received from few of the attendees:

“What a fascinating three hours with you that was last week. I very much look forward to attending your future talks.”

“I would like to particularly thank you for the AI course that you presented. I found it very informative and very well presented. Look forward to hearing about any further courses in the future.”

“Thank you very much for a stimulating – albeit whirlwind – introduction to the dimensions of artificial intelligence.”

“I very much enjoyed the course. Well worthwhile for me.”

So, yes, I think it worked well and am looking forward to offering it again in 2025.

–x–x–

Copyright Notice: the course design described in this article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/)

On the physical origins of modern AI – an explainer on the 2024 Nobel for physics

My first reaction when I heard that John Hopfield and Geoffrey Hinton had been awarded the Physics Nobel was – “aren’t there any advances in physics that are, perhaps, more deserving?” However, after a bit of reflection, I realised that this was a canny move on part of the Swedish Academy because it draws attention to the fact that some of the inspiration for the advances in modern AI came from physics. My aim in this post is to illustrate this point by discussing (at a largely non-technical level) two early papers by the laureates which are referred to in the Nobel press release.

The first paper is “Neural networks and physical systems with emergent collective computational abilities“, published by John Hopfield in 1982 and the second is entitled, “A Learning Algorithm for Boltzmann Machines,” published by David Ackley, Geoffrey Hinton and Terrence Sejnowski in 1985.

–x–

Some context to begin with: in the early 1980s, new evidence on the brain architecture had led to a revived interest in neural networks, which were first proposed by Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts in this paper in the early 1940s! Specifically, researchers realised that, like brains, neural networks could potentially be used to encode knowledge via weights in connections between neurons. The search was on for models / algorithms that demonstrated this. The papers by Hopfield and Hinton described models which could encode patterns that could be recalled, even when prompted with imperfect or incomplete examples.

Before describing the papers, a few words on their connection to physics:

Both papers draw on the broad field of Statistical Mechanics, a branch of physics that attempts to derive macroscopic properties of objects such as temperature and pressure from the motion of particles (atoms, molecules) that constitute them.

The essence of statistical mechanics lies in the empirically observed fact that large collections of molecules, when subjected to the same external conditions, tend to display the same macroscopic properties. This, despite the fact the individual molecules are moving about at random speeds and in random directions. James Clerk Maxwell and Ludwig Boltzmann derived the mathematical equation that describes the fraction of particles that have a given speed for the special case of an ideal gas – i.e., a gas in which there are no forces between molecules. The equation can be used to derive macroscopic properties such as the total energy, pressure etc.

Other familiar macroscopic properties such as magnetism or the vortex patterns in fluid flow can (in principle) also be derived from microscopic considerations. The key point here is that the collective properties (such as pressure or magnetism) are insensitive to microscopic details of what is going in the system.

With that said about the physics connection, let’s move on to the papers.

–x–

In the introduction to his paper Hopfield poses the following question:

“…physical systems made from a large number of simple elements, interactions among large numbers of elementary components yield collective phenomena such as the stable magnetic orientations and domains in a magnetic system or the vortex patterns in fluid flow. Do analogous collective phenomena in a system of simple interacting neurons have useful “computational” correlates?”

The inspired analogy between molecules and neurons led him to propose the mathematical model behind what are now called Hopfield Networks (which are cited in the Nobel press release). Analogous to the insensitivity of the macroscopic properties of gases to the microscopic dynamics of molecules, he demonstrated that a neural network in which each neuron has simple properties can display stable collective computational properties. In particular the network model he constructed displayed persistent “memories” that could be reconstructed from smaller parts of the network. As Hopfield noted in the conclusion to the paper:

“In the model network each “neuron” has elementary properties, and the network has little structure. Nonetheless, collective computational properties spontaneously arose. Memories are retained as stable entities or Gestalts and can be correctly recalled from any reasonably sized subpart. Ambiguities are resolved on a statistical basis. Some capacity for generalization is present, and time ordering of memories can also be encoded.”

–x–

Hinton’s paper, which followed Hopfield’s by a couple of years, describes a network “that is capable of learning the underlying constraints that characterize a domain simply by being shown examples from the domain.” Their network model, which they christened “Boltzmann Machine” for reasons I’ll explain shortly, could (much like Hopfield’s model) reconstruct a pattern from a part thereof. In their words:

“The network modifies the strengths of its connections so as to construct an internal generative model that produces examples with the same probability distribution as the examples it is shown. Then, when shown any particular example, the network can “interpret” it by finding values of the variables in the internal model that would generate the example. When shown a partial example, the network can complete it by finding internal variable values that generate the partial example and using them to generate the remainder.”

They developed a learning algorithm that could encode the (constraints implicit in a) pattern via the connection strengths between neurons in the network. The algorithm worked but converged very slowly. This limitation is what led Hinton to later invent Restricted Boltzmann Machines, but that’s another story.

Ok, so why the reference to Boltzmann? The algorithm (both the original and restricted versions) uses the well-known gradient descent method to minimise an objective function, which in this case is an expression for energy. Students of calculus will know that gradient descent is prone to getting stuck in local minima. The usual way to get out of these minima is to take occasional random jumps to higher values of the objective function. The decision rule Hinton and Co use to determine whether or not to make the jump is such that the overall probabilities of the two states converges to a Boltzmann distribution (different from, but related to, the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution mentioned earlier). It turns out that the Boltzmann distribution is central to statistical mechanics, but it would take me too far afield to go into that here.

–x–

Hopfield networks and Boltzmann machines may seem far removed from today’s neural networks. However, it is important to keep in mind that they heralded a renaissance in connectionist approaches to AI after a relatively lean period in the 1960s and 70s. Moreover, vestiges of the ideas implemented in these pioneering models can be seen in some popular architectures today ranging from autoencoders to recurrent neural networks (RNNs).

That’s a good note to wrap up on, but a few points before I sign off:

Firstly, a somewhat trivial matter: it is simply not true that physics Nobels have not been awarded for applied work in the past. A couple of cases in point are the 1909 prize awarded to Marconi and Braun for the invention of wireless telegraphy, and the 1956 prize to Shockley, Bardeen and Brattain for the discovery of the transistor effect, the basis of the chip technology that powers AI today.

Secondly: the Nobel committee, contrary to showing symptoms of “AI envy”, are actually drawing public attention to the fact that the practice of science, at its best, does not pay heed to the artificial disciplinary boundaries that puny minds often impose on it.

Finally, a much broader and important point: inspiration for advances in science often come from finding analogies between unrelated phenomena. Hopfield and Hinton’s works are not rare cases. Indeed, the history of science is rife with examples of analogical reasoning that led to paradigm-defining advances.

–x–x–