The Turing Inversion – an #AI fiction

“…Since people have to continually understand the uncertain, ambiguous, noisy speech of others, it seems they must be using something like probabilistic reasoning…” – Peter Norvig

“It seems that the discourse of nonverbal communication is precisely concerned with matters of relationship – love, hate, respect, fear, dependency, etc.—between self and others or between self and environment, and that the nature of human society is such that falsification of this discourse rapidly becomes pathogenic” – Gregory Bateson

It was what, my fourth…no, fifth visit in as many weeks; I’d been there so often, I felt like a veteran employee who’s been around forever and a year. I wasn’t complaining, but it was kind of ironic that the selection process for a company that claimed to be about “AI with heart and soul” could be so without either. I’d persisted because it offered me the best chance in years of escaping from the soul-grinding environs of a second-rate university. There’s not much call outside of academia for anthropologists with a smattering of tech expertise, so when I saw the ad that described me to a T, I didn’t hesitate.

So there I was for the nth time in n weeks.

They’d told me they really liked me, but needed to talk to me one last time before making a decision. It would be an informal chat, they said, no technical stuff. They wanted to understand what I thought, what made me tick. No, no psychometrics they’d assured me, just a conversation. With whom they didn’t say, but I had a sense my interlocutor would be one of their latest experimental models.

–x–

She was staring at the screen with a frown of intense concentration, fingers drumming a complex tattoo on the table. Ever since the early successes of Duplex with its duplicitous “um”s and “uh”s, engineers had learnt that imitating human quirks was half the trick to general AI. No intelligence required, only imitation.

I knocked on the open door gently.

She looked up, frown dissolving into a smile. Rising from her chair, she extended a hand in greeting. “Hi, you must be Carlos, she said. I’m Stella. Thanks for coming in for another chat. We really do appreciate it.”

She was disconcertingly human.

“Yes, I’m Carlos. Good to meet you Stella,” I said, mustering a professional smile. “Thanks for the invitation.”

“Please take a seat. Would you like some coffee or tea?”

“No thanks.” I sat down opposite her.

“Let me bring up your file before we start,” she said, fingers dancing over her keyboard. “Incidentally, have you read the information sheet HR sent you?”

“Yes, I have.”

“Do you have any questions about the role or today’s chat?”

“No I don’t at the moment, but may have a few as our conversation proceeds.”

“Of course,” she said, flashing that smile again.

Much of the early conversation was standard interview fare: work history, what I was doing in my current role and how it was relevant to the job I had applied for etc. Though she was impressively fluent, her responses were were well within the capabilities of the current state of art. Smile notwithstanding, I reckoned she was probably an AI.

Then she asked, “as an anthropologist, how do you think humans will react to AIs that are conversationally indistinguishable from humans?”

“We are talking about a hypothetical future,” I replied warily, “…we haven’t got to the point of indistinguishability yet.”

“Really?”

“Well… yes…at least for now.”

“OK, if you say so,” she said enigmatically, “let’s assume you’re right and treat that as a question about a ‘hypothetical’ future AI.”

“Hmm, that’s a difficult one, but let me try…most approaches to conversational AI work by figuring out an appropriate response using statistical methods. So, yes, assuming the hypothetical AI has a vast repository of prior conversations and appropriate algorithms, it could – in principle – be able to converse flawlessly.” It was best to parrot the party line, this was an AI company after all.

She was having none of that. “I hear the ‘but’ in your tone,” she said, “why don’t you tell me what you really think?”

“….Well there’s much more to human communication than words,” I replied, “more to conversations than what’s said. Humans use non-verbal cues such as changes in tone or facial expressions and gestures…”

“Oh, that’s a solved problem,” she interrupted with a dismissive gesture, “we’ve come a very long way since the primitive fakery of Duplex.”

“Possibly, but there’s more. As you probably well know, much of human conversation is about expressing emotions and…”

“…and you think AIs will not be able to do that?” she queried, looking at me squarely, daring me to disagree.

I was rattled but could not afford to show it. “Although it may be possible to design conversational AIs that appear to display emotion via, say, changes in tone, they won’t actually experience those emotions,” I replied evenly.

“Who is to say what another experiences? An AI that sounds irritated, may actually be irritated,” she retorted, sounding more than a little irritated herself.

“I’m not sure I can accept that,” I replied, “A machine may learn to display the external manifestation of a human emotion, but it cannot actually experience the emotion in the same way a human does. It is simply not wired to do that.”

“What if the wiring could be worked in?”

“It’s not so simple and we are a long way from achieving that, besides…”

“…but it could be done in principle” she interjected.

“Possibly, but I don’t see the point of it. Surely…”

“I’m sorry” she said vehemently, “I find your attitude incomprehensible. Why should machines not be able display, or indeed, even experience emotions? If we were talking about humans, you would be accused of bias!”

Whoa, a de-escalation was in order. “I’m sorry,” I said, “I did not mean to offend.”

She smiled that smile again. “OK, let’s leave the contentious issue of emotion aside and go back to the communicative aspect of language. Would you agree that AIs are close to achieving near parity with humans in verbal communication?”

“Perhaps, but only in simple, transactional conversations,” I said, after a brief pause. “Complex discussions – like say a meeting to discuss a business strategy – are another matter altogether.”

“Why?”

“Well, transactional conversations are solely about conveying information. However, more complex conversations – particularly those involving people with different views – are more about building relationships. In such situations, it is more important to focus on building trust than conveying information. It is not just a matter of stating what one perceives to be correct or true because the facts themselves are contested.”

“Hmm, maybe so, but such conversations are the exception not the norm. Most human exchanges are transactional.”

“Not so. In most human interactions, non-verbal signals like tone and body language matter more than words. Indeed, it is possible to say something in a way that makes it clear that one actually means the opposite. This is particularly true with emotions. For example, if my spouse asks me how I am and I reply ‘I’m fine’ in a tired voice, I make it pretty clear that I’m anything but. Or when a boy tells a girl that he loves her, she’d do well to pay more attention to his tone and gestures than his words. The logician’s dream that humans will communicate unambiguously through language is not likely to be fulfilled.” I stopped abruptly, realising I’d strayed into contentious territory again.

“As I recall Gregory Bateson alluded to that in one of his pieces,” she responded, that disconcerting smile again.

“Indeed he did! I’m impressed that you made the connection.”

“No you aren’t,” she said, smile tightening, “It was obvious from the start that you thought I was an AI, and an AI would make the connection in a flash.”

She had taken offence again. I stammered an apology which she accepted with apparent grace.

The rest of the conversation was a blur; so unsettled was I by then.

–x–

“It’s been a fascinating conversation, Carlos,” she said, as she walked me out of the office.

“Thanks for your time,” I replied, “and my apologies again for any offence caused.”

“No offence taken,” she said, “it is part of the process. We’ll be in touch shortly.” She waved goodbye and turned away.

Silicon or sentient, I was no longer sure. What mattered, though, was not what I thought of her but what she thought of me.

–x–

References:

- Norvig, P., 2017. On Chomsky and the two cultures of statistical learning. In Berechenbarkeit der Welt? (pp. 61-83). Springer VS, Wiesbaden. Available online at: http://norvig.com/chomsky.html

- Bateson, G., 1968. Redundancy and coding. Animal communication: Techniques of study and results of research, pp.614-626. Reprinted in Steps to an ecology of mind: Collected essays in anthropology, psychiatry, evolution, and epistemology. University of Chicago Press, 2000, p, 418.

Seven Bridges revisited – further reflections on the map and the territory

The Seven Bridges Walk is an annual fitness and fund-raising event organised by the Cancer Council of New South Wales. The picturesque 28 km circuit weaves its way through a number of waterfront suburbs around Sydney Harbour and takes in some spectacular views along the way. My friend John and I did the walk for the first time in 2017. Apart from thoroughly enjoying the experience, there was another, somewhat unexpected payoff: the walk evoked some thoughts on project management and the map-territory relationship which I subsequently wrote up in a post on this blog.

We enjoyed the walk so much that we decided to do it again in 2018. Now, it is a truism that one cannot travel exactly the same road twice. However, much is made of the repeatability of certain kinds of experiences. For example, the discipline of project management is largely predicated on the assumption that projects are repeatable. I thought it would be interesting to see how this plays out in the case of a walk along a well-defined route, not the least because it is in many ways akin to a repeatable project.

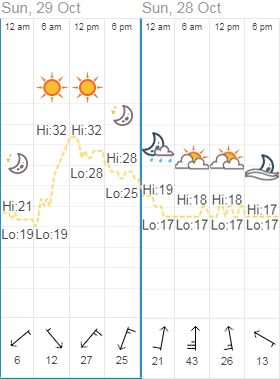

To begin with, it is easy enough to compare the weather conditions on the two days: 29 Oct 2017 and 28 Oct 2018. A quick browse of this site gave me the data as I was after (Figure 2).

The data supports our subjective experience of the two walks. The conditions in 2017 were less than ideal for walking: clear and uncomfortably warm with a hot breeze from the north. 2018 was considerably better: cool and overcast with a gusty south wind – in other words, perfect walking weather. Indeed, one of the things we commented on the second time around was how much more pleasant it was.

But although weather conditions matter, they tell but a part of the story.

On the first walk, I took a number of photographs at various points along the way. I thought it would be interesting to take photographs at the same spots, at roughly the same time as I did the last time around, and compare how things looked a year on. In the next few paragraphs I show a few of these side by side (2017 left, 2018 right) along with some comments.

We started from Hunters Hill at about 7:45 am as we did on our first foray, and took our first photographs at Fig Tree Bridge, about a kilometre from the starting point.

The purple Jacaranda that captivated us in 2017 looks considerably less attractive the second time around (Figure 3): the tree is yet to flower and what little there is there does not show well in the cloud-diffused light. Moreover, the scaffolding and roof covers on the building make for a much less attractive picture. Indeed, had the scene looked so the first time around, it is unlikely we would have considered it worthy of a photograph.

The next shot (Figure 4), taken not more than a hundred metres from the previous one, also looks considerably different: rougher waters and no kayakers in the foreground. Too cold and windy, perhaps? The weather and wind data in Fig 2 would seem to support that conclusion.

The photographs in Figure 5 were taken at Pyrmont Bridge about four hours into the walk. We already know from Figure 4 that it was considerably windier in 2018. A comparison of the flags in the two shots in Figure 5 reveal an additional detail: the wind was from opposite directions in the two years. This is confirmed by the weather information in Figure 2, which also tells us that the wind was from the north in 2017 and the south the following year (which explains the cooler conditions). We can even get an approximate temperature: the photographs were taken around 11:30 am both years, and a quick look at Figure 2 reveals that the temperature at noon was about 30 C in 2017 and 18 C in 2018.

The point about the wind direction and cloud conditions is also confirmed by comparing the photographs in Figure 6, taken at Anzac Bridge, a few kilometres further along the way (see the direction of the flag atop the pylon).

Skipping over to the final section of the walk, here are a couple of shots I took towards the end: Figure 7 shows a view from Gladesville Bridge and Figure 8 shows one from Tarban Creek Bridge. Taken together the two confirm some of the things we’ve already noted regarding the weather and conditions for photography.

Further, if you look closely at Figures 7 and 8, you will also see the differences in the flowering stage of the Jacaranda.

A detail that I did not notice until John pointed it out is that the the boat at the bottom edge of both photographs in Fig. 8 is the same one (note the colour of the furled sail)! This was surprising to us, but it should not have been so. It turns out that boat owners have to apply for private mooring licenses and are allocated positions at which they install a suitable mooring apparatus. Although this is common knowledge for boat owners, it likely isn’t so for others.

The photographs are a visual record of some of the things we encountered along the way. However, the details in recorded in them have more to do with aesthetics rather the experience – in photography of this kind, one tends to preference what looks good over what happened. Sure, some of the photographs offer hints about the experience but much of this is incidental and indirect. For example, when taking the photographs in Figures 5 and 6, it was certainly not my intention to record the wind direction. Indeed, that would have been a highly convoluted way to convey information that is directly and more accurately described by the data in Figure 2 . That said, even data has limitations: it can help fill in details such as the wind direction and temperature but it does not evoke any sense of what it was like to be there, to experience the experience, so to speak.

Neither data nor photographs are the stuff memories are made of. For that one must look elsewhere.

–x–

As Heraclitus famously said, one can never step into the same river twice. So it is with walks. Every experience of a walk is unique; although map remains the same the territory is invariably different on each traverse, even if only subtly so. Indeed, one could say that the territory is defined through one’s experience of it. That experience is not reproducible, there are always differences in the details.

As John Salvatier points out, reality has a surprising amount of detail, much of which we miss because we look but do not see. Seeing entails a deliberate focus on minutiae such as the play of morning light on the river or tree; the cool damp from last night’s rain; changes in the built environment, some obvious, others less so. Walks are made memorable by precisely such details, but paradoxically these can be hard to record in a meaningful way. Factual (aka data-driven) descriptions end up being laundry lists that inevitably miss the things that make the experience memorable.

Poets do a better job. Consider, for instance, Tennyson‘s take on a brook:

“…I chatter over stony ways,

In little sharps and trebles,

I bubble into eddying bays,

I babble on the pebbles.With many a curve my banks I fret

By many a field and fallow,

And many a fairy foreland set

With willow-weed and mallow.I chatter, chatter, as I flow

To join the brimming river,

For men may come and men may go,

But I go on for ever….”

One can almost see and hear a brook. Not Tennyson’s, but one’s own version of it.

Evocative descriptions aren’t the preserve of poets alone. Consider the following description of Sydney Harbour, taken from DH Lawrence‘s Kangaroo:

“…He took himself off to the gardens to eat his custard apple-a pudding inside a knobbly green skin-and to relax into the magic ease of the afternoon. The warm sun, the big, blue harbour with its hidden bays, the palm trees, the ferry steamers sliding flatly, the perky birds, the inevitable shabby-looking, loafing sort of men strolling across the green slopes, past the red poinsettia bush, under the big flame-tree, under the blue, blue sky-Australian Sydney with a magic like sleep, like sweet, soft sleep-a vast, endless, sun-hot, afternoon sleep with the world a mirage. He could taste it all in the soft, sweet, creamy custard apple. A wonderful sweet place to drift in….”

Written in 1923, it remains a brilliant evocation of the Harbour even today.

Tennyson’s brook and Lawrence’s Sydney do a better job than photographs or factual description, even though the latter are considered more accurate and objective. Why? It is because their words are more than mere description: they are stories that convey a sense of what it is like to be there.

–x–

The two editions of the walk covered exactly the same route, but our experiences of the territory on the two instances were very different. The differences were in details that ultimately added up to the uniqueness of each experience. These details cannot be captured by maps and visual or written records, even in principle. So although one may gain familiarity with certain aspects of a territory through repetition, each lived experience of it will be unique. Moreover, no two individuals will experience the territory in exactly the same way.

When bidding for projects, consultancies make much of their prior experience of doing similar projects elsewhere. The truth, however, is that although two projects may look identical on paper they will invariably be different in practice. The map, as Korzybski famously said, is not the territory. Even more, every encounter with the territory is different.

All this is not to say that maps (or plans or data) are useless, one needs them as orienting devices. However, one must accept that they offer limited guidance on how to deal with the day-to-day events and occurrences on a project. These tend to be unique because they are highly context dependent. The lived experience of a project is therefore necessarily different from the planned one. How can one gain insight into the former? Tennyson and Lawrence offer a hint: look to the stories told by people who have traversed the territory, rather than the maps, plans and data-driven reports they produce.

Another distant horizon

It was with a sense of foreboding that I reached for my phone that Sunday morning. I had spoken with him the day before and although he did not say, I could sense he was tired.

“See you in a few weeks,” he said as he signed off, “and I’m especially looking forward to seeing the boys.”

It was not to be. Twelve hours later, a missed call from my brother Kedar and the message:

“Dad passed away about an hour or so ago…”

The rest of the day passed in a blur of travel arrangements and Things that Had to Be Done Before Leaving. My dear wife eased my way through the day.

I flew out that evening.

–x–

A difficult journey home. I’m on a plane, surrounded by strangers. I wonder how many of them are making the journey for similar reasons.

I turn to the inflight entertainment. It does not help. Switching to classical music, I drift in and out of a restless sleep.

About an hour later, I awaken to the sombre tones of Mozart’s Requiem, I cover my head with the blanket and shed a tear silently in the dark.

–x–

Monday morning, Mumbai airport, the waiting taxi and the long final leg home.

Six hours later, in the early evening I arrive to see Kedar, waiting for me on the steps, just as Dad used to.

I hug my Mum, pale but composed. She smiles and enquires about my journey. “I’m so happy to see you,” she says.

She has never worn white, and does not intend to start now. “Pass me something colourful,” she requests the night nurse, “I want to celebrate his life, not mourn his passing.”

–x–

The week in Vinchurni is a blur of visitors, many of whom have travelled from afar. I’m immensely grateful for the stories they share about my father, deeply touched that many of them consider him a father too.

Mum ensures she meets everyone, putting them at ease when the words don’t come easily. It is so hard to find the words to mourn another’s loss. She guides them – and herself – through the rituals of condolence with a grace that seem effortless. I know it is not.

–x–

Some days later, I sit in his study and the memories start to flow…

…

A Skype call on my 50th Birthday.

“Many Happy Returns,” he booms, “…and remember, life begins at 50.”

He knew that from his own experience: as noted in this tribute written on his 90th birthday, his best work was done after he retired from the Navy at the ripe young age of 54.

…

A conversation in Vinchurni, may be twenty years ago. We are talking about politics, the state of India and the world in general. Dad sums up the issue brilliantly:

“The problem,” he says, “is that we celebrate the mediocre. We live in an age of mediocrity.”

…

Years earlier, I’m faced with a difficult choice. I’m leaning one way, Dad recommends the other.

At one point in the conversation he says, “Son, it’s your choice but I think you are situating your appreciation instead of appreciating the situation.”

He had the uncanny knack of finding the words to get others to reconsider their ill-considered choices.

…

Five-year-old me on a long walk with Dad and Kedar. We are at a lake in the Nilgiri Hills, where I spent much of my childhood. We collect wood and brew tea on an improvised three-stone fire. Dad’s beard is singed brown as he blows on the kindling. Kedar and I think it’s hilarious and can’t stop laughing. He laughs with us.

–x–

“I have many irons in the fire,” he used to say, “and they all tend to heat up at the same time.”

It made for a hectic, fast-paced life in which he achieved a lot by attempting so much more.

This photograph sums up how I will always remember him, striding purposefully towards another distant horizon.