On the anticipation of unintended consequences

A couple of weeks ago I bought an anthology of short stories entitled, An Exploration of Unintended Consequences, written by a school friend, Ajit Chaudhuri. I started reading and couldn’t stop until I got to the last page a couple of hours later. I’ll get to the book towards the end of this piece, but first, a rather long ramble about some thoughts which have been going around my head since I read it.

–x–

Many (most?) of the projects we undertake, or even the actions we perform, both at work and in our personal lives have unexpected side-effects or results that overshadow their originally intended outcomes. To be clear, unexpected does not necessarily mean adverse – consider, for example, Adam Smith’s invisible hand. However, it is also true – at least at the level of collectives (organisations or states) – that negative outcomes far outnumber positive ones. The reason this happens can be understood from a simple argument based on the notion of entropy – i.e., the fact that disorder is far more likely than order. Anyway, as interesting as that may be, it is tangential to the question I want to address in this post, which is:

Is it possible to plan and act in a way which anticipates, or even encourages, positive unintended consequences?

Let’s deal with the “unintended” bit first. And you may ask: does the question make sense? Surely, if an outcome is unintended, then it is necessarily unanticipated (let alone positive).

But is that really so? In this paper, Frank DeZwart, suggests it isn’t. In particular, he notes that, ” if unintended effects are anticipated, they are a different phenomenon as they follow from purposive choice and not, like unanticipated effects, from ignorance, error, or ideological blindness.”

As he puts it, “unanticipated consequences can only be unintended, but unintended consequences can be either anticipated or unanticipated.”

So the question posed earlier makes sense, and the key to answering it lies in understanding the difference between purposive and purposeful choice (or action).

–x–

In a classic paper that heralded the birth of cybernetics, Rosenblueth, Wiener and Bigelow noted that, “the term purposeful is meant to denote that the act or behavior may be interpreted as directed to the attainment of a goal-i.e., to a final condition in which the behaving object reaches a definite correlation in time or in space with respect to another object or event.”

Aside 1: The reader will notice that the definition has a decidedly scientific / engineering flavour. So, it is not surprising that philosophers jumped into the fray, and arguments around finer points of the definition ensued (see this sequence of papers, for example). Although interesting, we’ll ignore the debate as it will take us down a rabbit hole from which there is no return.

Aside 2: Interestingly, the Roseblueth-Wiener-Bigelow paper along with this paper by Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts laid the foundation for cybernetics. A little known fact is that the McCulloch-Pitts paper articulated the basic ideas behind today’s neural networks and Nobel Prize glory, but that’s another story.

Back to our quest: the Rosenblueth-Wiener definition of purposefulness has two assumptions embedded in it:

a) that the goal is well-defined (else, how will an actor know it has been achieved?), and

b) the actor is aware of the goal (else, how will an actor know what to aim for?)

We’ll come back to these in a bit, but let’s continue with the purposeful / purposive distinction first.

As I noted earlier, the cybernetic distinction between purposefulness and purposiveness led to much debate and discussion. Much of the difference of opinion arises from the ways in which diverse disciplines interpret the term. To avoid stumbling into that rabbit hole, I’ll stick to definitions of purposefulness / purposiveness from systems and management domains.

–x–

The first set of definitions is from a 1971 paper by Russell Ackoff in which he attempts to set out clear definitions of systems thinking concepts for management theorists and professionals.

Here are his definitions for purposive and purposeful systems:

“A purposive system is a multi-goal seeking system the different goals of which have a common property. Production of that property is the system’s purpose. These types of systems can pursue different goals, but they do not select the goal to be pursued. The goal is determined by the initiating event. But such a system does choose the means by which to pursue its goals.”

and

“A purposeful system is one which can produce the same outcome in different ways…[and] can change its goals under constant conditions – it selects ends as well as means and thus displays will. Human beings are the most familiar examples of such systems.”

Ackoff’s purpose(!) in making the purposive/purposeful distinction was to clarify the difference between apparent purpose displayed by machines (computers) which he calls purposiveness, and “true” or willed (or human) purpose which he calls purposefulness. Although this seems like a clear cut distinction, it falls apart on closer inspection. The example Ackoff gives for a purposive system is that of a computer which is programmed to play multiple games – say noughts-and-crosses and checkers. The goal differs depending on which game it plays, but the common property is winning. However, this feels like an artificial distinction: surely winning is a goal, albeit a higher-order one.

–x–

The second set of definitions, due to Peter Checkland, is taken from this module from an Open University course on managing complexity:

“Two forms of behaviour in relation to purpose have also been distinguished. One is purposeful behaviour, which [can be described] as behaviour that is willed – there is thus some sense of voluntary action. The other is purposive behaviour – behaviour to which an observer can attribute purpose. Thus, in the example of the government minister, if I described his purpose as meeting some political imperative, I would be attributing purpose to him and describing purposive behaviour. I might possibly say his intention was to deflect the issue for political reasons. Of course, if I were to talk with him I might find out this was not the case at all. He might have been acting in a purposeful manner which was not evident to me.”

This distinction is strange because the definitions of the two terms are framed from two different perspectives – that of an actor and that of an observer. Surely, when one makes a distinction, one should do so from a single perspective.

…and yet, there is something in this perspective shift which I’ll come back to in a bit.

–x–

The third set of definitions is from Robert Chia and Robin Holt’s classic, Strategy Without Design: The Silent Efficacy of Indirect Action:

“Purposive action is action taken to alleviate ourselves from a negative situation we find ourselves in. In everyday engagements, we might act to distance ourselves from an undesirable situation we face, but this does not imply having a pre-established end goal in mind. It is a moving away from rather than a moving towards that constitutes purposive actions. Purposeful actions, on the other hand, presuppose having a desired and clearly articulated end goal that we aspire towards. It is a product of deliberate intention“

Finally, here is a distinction we can work with:

- Purposive actions are aimed at alleviating negative situations (note, this can be framed in a better way, and I’ll get to that shortly)

- Purposeful actions are those aimed at achieving a clearly defined goal.

The interesting thing is that the above definition of purposive action is consistent with the two observations I made earlier regarding the original Rosenbluth-Wiener-Bigelow definition of purposeful systems

a) purposive actions have no well-defined end-state (alleviating a negative situation says nothing about what the end-state will look like). That said, someone observing the situation could attribute purpose to the actor because the behaviour appears to be purposeful (see Checkland’s definition above).

b) as the end-state is undefined, the purposive actor cannot know it. However, this need not stop the actor from envisioning what it ought to look like (and indeed, most purposive actors will).

In a later paper Chia, wrote, , “…[complex transformations require] an implicit awareness that the potentiality inherent in a situation can be exploited to one’s advantage without adverse costs in terms of resources. Instead of setting out a goal for our actions, we could try to discern the underlying factors whose inner configuration is favourable to the task at hand and to then allow ourselves to be carried along by the momentum and propensity of things.”

Inspired by this, I think it is appropriate to reframe the Chia-Holt definition more positively, by rephrasing it as follows:

“Purposive action is action which exploits the inherent potential in a situation so as to increase the likelihood of positive outcomes for those who have a stake in the situation”

The above statement includes the Chia-Holt definition as such an action could be a moving away from a negative situation. However, it could also be an action that comes from recognising an opportunity that would otherwise remain unexploited.

–x–

And now, I can finally answer the question I raised at the start regarding anticipated unintended consequences. In brief:

A purposive action, as I have defined above, is one that invariably leads to anticipated unintended consequences.

Moreover, its consequences are often (usually?) positive, even though the specific outcomes are generally impossible to articulate at the start.

Purposive action is at the heart of emergent design, which is based on doing things that increase the probability of organisational success, but in an unobtrusive manner which avoids drawing attention. Examples of such low-key actions based on recognising the inherent potential of situations are available in the Chia-Holt book referenced above and in the book I wrote with Alex Scriven.

I should also point out that since purposive action involves recognising the potential of an unfolding situation, there is necessarily an improvisational aspect to it. Moreover, since this potential is typically latent and not obvious to all stakeholders, the action should be taken in a way that does not change the dynamics of the situation. This is why oblique or indirect actions tend to work better than highly visible, head-on ones. Developing the ability to act in such a manner is more about cultivating a disposition that tolerates ambiguity than learning to follow prescribed rules, models or practices.

–x–

So much for purposive action at the level of collectives. Does it, can it, play a role in our individual lives?

The short answer is: yes it can. A true story might help clarify:

“I can’t handle failure,” she said. “I’ve always been at the top of my class.”

She was being unduly hard on herself. With little programming experience or background in math, machine learning was always going to be hard going. “Put that aside for now,” I replied. “Just focus on understanding and working your way through it, one step at a time. In four weeks, you’ll see the difference.”

“OK,” she said, “I’ll try.”

She did not sound convinced but to her credit, that’s exactly what she did. Two months later she completed the course with a distinction.

“You did it!” I said when I met her a few weeks after the grades were announced.

“I did,” she grinned. “Do you want to know what made the difference?”

Yes, I nodded.

“Thanks to your advice, I stopped treating it like a game I had to win,” she said, “and that took the pressure right off. I then started to enjoy learning.”

–x–

And this, finally, brings me back to the collection of short stories written by my friend Ajit. The stories are about purposive actions taken by individuals and their unintended consequences. Consistent with my discussion above, the specific outcomes in the stories could not have been foreseen by the protagonists (all women, by the way), but one can well imagine them thinking that their actions would eventually lead to a better place.

That aside, the book is worth picking up because the author is a brilliant raconteur: his stories are not only entertaining, they also give readers interesting insights into everyday life in rural and urban India. The author’s note at the end gives some background information and further reading for those interested in the contexts and settings of the stories.

I found Ajit’s use of inset stories – tales within tales – brilliant. The anthropologist, Mary Catherine Bateson, once wrote, “an inset story is a standard hypnotic device, a trance induction device … at the most obvious level, if we are told that Scheherazade told a tale of fantasy, we are tempted to believe that she, at least, is real.” Ajit uses this device to great effect.

Finally, to support my claim that the stories are hugely entertaining, here are a couple of direct quotes from the book:

The line “Is there anyone here at this table who, deep down, does not think that her husband is a moron?” had me laughing out loud. My dear wife asked me what’s up. I told her; she had a good laugh too, and from the tone of her laughter, it was clear she agreed.

Another one: “…some days I’m the pigeon and some days I’m the statue. It’s just that on the days that I’m the pigeon, I try to remember what it is like to be the statue. And on the days that I’m the statue, I try not to think.” Great advice, which I’ve passed on to my two boys.

–x–

I called Ajit the other day and spoke to him for the first time in over 40 years; another unintended consequence of reading his book.

–x—x–

The Shot Tower – reflections on surprise and serendipity

A year on from my walk to the elusive arch, I found myself on another trail in Tasmania with my friend Daniel. This time around, we decided to do a more leisurely walk, with no particular destination or distance in mind. He suggested taking the Alum Cliffs Trail, a moderate grade coastal walk close to Hobart. As expected, there were some spectacular views along the way but the real surprise was the curious structure shown below:

“What’s that?” I asked, pointing at the tower.

“Oh, that’s the shot tower, ” replied Daniel.

That sounded vaguely familiar but I couldn’t be sure. “What’s it for?”

“No idea,” came the reply.

As we got closer, we saw that it was open.

We stepped in.

–x–

Science concerns itself with explanation. However, although explanations tell us why phenomena or events occur as they do, narratives tell us how they unfold. Both are concerned with sequences of events, but there is a world of difference in their aims – explanations are intended to be conclusive whereas narratives open up new possibilities. As James Carse noted in his book Finite and Infinite Games,

“Explanations settle issues, showing that matters must end as they have. Narratives raise issues, showing that matters do not end as they must but as they do. Explanation sets the need for further inquiry aside; narrative invites us to rethink what we thought we knew.”

If this is true, then science is [or ought to be] more about crafting narratives that provoke questions than finding explanations that resolve them. One of the dirty secrets of science is that no one really knows where good hypotheses come from. When asked, great scientists offer responses like the one below:

“The supreme task of the physicist is to arrive at those universal elementary laws from which the cosmos can be built up by pure deduction. There is no logical path to these laws; only intuition, resting on sympathetic understanding of experience, can reach them.”

These lines are from a 1918 lecture by Einstein.

–x–

Stepping into the shot tower was a step back in time, to thirty years ago when I had just started a PhD in Chemical Engineering.

Given my math and physics background, I gravitated towards the mathematically-oriented field of fluid dynamics, but I had a lot of reading and learning to do. I spent a few months trying to define a decent research problem but made little progress.

After about a year my supervisor decided to push. He suggested that I work on a practical problem linked to his consulting work. It had to do with improving a shot-making process for a mining company. Incidentally, shot is a term used to refer to spherical metal pellets.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, shot was commonly used as ammunition in various firearms. Ideally, shot pellets should be perfectly spherical. The key problem faced by shot-makers in the 18th century was the design of a manufacturing process that would enable the production of shot of acceptable quality (uniform size and sphericity) at scale.

William Watts solved this problem in the late 18th century using an ingenious idea: let uniformly sized drops of molten metal to free-fall from a height. While falling they will tend to form spheres due to the effect of surface tension (the force that the interior metal atoms exert on the surface atoms). Why spheres? Answer: because the most energetically favourable shape for a metal drop of a fixed volume is one that minimizes the surface area, and the 3d shape that has the smallest surface area for a given volume is a sphere.

This reasoning is what led Watts to add a three storey tower to his own house in the 1780s and start producing shot from his home factory.

–x–

As we made our way up the tower, the kids started asking questions.

“Why is there big bucket down there? Asked one, peering down the central shaft as we made our way up the narrow spiral stairway.

“What’s with the stove at the top – it’s a terrible place for a kitchen? Asked the other when we got to the top.

I was surprised at how their questions and observations reminded me of what I once knew well but had since forgotten:

“Molten lead would be dropped from the top of the tower. Like most liquids, surface tension makes drops of molten lead become near-spherical as they fall. When the tower is high enough, the lead droplets will solidify during the fall and thus retain their spherical form. Water is usually placed at the bottom of the tower, cooling the lead immediately upon landing.” – from the Wikipedia article on shot

And so on. There are several engineering challenges around ensuring uniform drop sizes. For example, as the shot size increases, the drops of molten metal needs to be released from a greater height.

On our way out, we spent some time browsing the photographs and artefacts in the small museum at the base of the tower. I launched into an impromptu lecture on the physics of jet breakup, again surprised at how much I could recall.

“Interesting,” said Daniel politely, “so is this what your Phd was about? Shot-making?”

“No,” I said, “I ended up working on another related problem, and that’s another story.”

And as I said that, I realised the unforeseen and unplanned turn my research took thirty odd years ago was not so different from what had happened on our walk that day.

–x–

One October evening 1995, about a year into my shot-making project, I was washing up after dinner when I noticed a curious wave-like structure on the thin jet that emerged from the kitchen sink tap and fell onto a plate an inch or two below the tap (the dishes had piled up that day). The wave pattern was stationary and rather striking.

The phenomenon is one that countless folks have seen. Indeed, I had noticed it before but never paid it much attention until that October evening when I saw the phenomenon with new eyes. Being familiar with the physics of jet breakup, I realised, at once, that the pattern had the same underlying cause. Wondering if anyone had published papers on it, I dashed off to the library to do a literature search (Google Scholar and decent search engines were still a few years away). Within a few hours I knew I’d stumbled on a phenomenon that would change the direction of my research.

The next day, I told my supervisor about it. He was just as excited about it as I was and was more than happy for me to switch topics. I worked feverishly on the problem and within a few months had a theory that related the wavelength of the waves to jet velocity and properties of the fluid. The work was not a major innovation, but it was novel enough to get me a degree and a couple of papers.

–x–

Here’s the thing, though. I came upon the phenomenon by accident. There was nothing planned about it, neither was there anything in my training that prepared me for it.

Much is made of the importance of having well-defined goals, both in scientific research and business. You know the spiel: without goals there can be no plans; to map out a route, you must know the destination etc.

However, it is all too easy to become fixated on achieving goals or arriving at a destination to the point where one ceases to pay attention to the journey. Much of the fun and learning is not in reaching one’s goal but in the events and encounters along the way. If we’d been fixated on the walk, we might have missed the opportunity to explore the tower.

As they say, it is the journey that matters, not the destination. Carse put it beautifully when he wrote,

“Copernicus was a traveler who…[dared] to look again at all that is familiar in the hope of vision. What we hear in this account is the ancient saga of the solitary wanderer… who risks anything for the sake of surprise. True, at a certain point he stopped to look and may have ended his journey…But what resounds most deeply in the life of Copernicus is the journey that made knowledge possible and not the knowledge that made the journey successful.”

A journey that seeks surprise necessarily involves taking paths to destinations unknown in preference to those that have been mapped out clearly. Our visit to the shot tower was not planned- indeed, I didn’t even know of its existence before that morning – but the half hour we spent there is what made our walk interesting and memorable.

–x–

A final word before I go, once again prompted by Carse:

“To be prepared against surprise is to be trained. To be prepared for surprise is to be educated. Education discovers an increasing richness in the past, because it sees what is unfinished there. Training regards the past as finished and the future as to be finished. Education leads toward a continuing self-discovery; training leads toward a final self-definition. Training repeats a completed past in the future. Education continues an unfinished past into the future.”

If Carse is right – and I think he is – our education system is all about training, not education. The many years I spent at universities taught me skills I could use to solve problems that were given to me, but not how to look at the world in wonder and find problems of my own. It was only towards the end of my time in university that I learnt the latter, and the irony is that I did so serendipitously.

–x–x–

Towards a public understanding of AI – notes from an introductory class for a general audience

There is a dearth of courses for the general public on AI. To address this gap, I ran a 3-hour course entitled “AI – A General Introduction” on November 4th at the Workers Education Association (WEA) office in Sydney. My intention was to introduce attendees to modern AI via a historical and cultural route, from its mystic 13th century origins to the present day. In this article I describe the content of the session, offering some pointers for those who would like to run similar courses.

–x–

First some general remarks about the session:

- The course was sold out well ahead of time – there is clearly demand for such offerings.

- Although many attendees had used ChatGPT or other similar products, none had much of an idea of how they worked or what they are good (and not so good) for.

- The session was very interactive with lots of questions. Attendees were particularly concerned about social implications of AI (job losses, medical applications, regulation).

- Most attendees did not have a technical background. However, judging from their questions and feedback, it seems that most of them were able to follow the material.

The biggest challenge in designing a course for the public is the question of prior knowledge – what one can reasonably assume the audience already knows. When asked this question, my contact at WEA said I could safely assume that most attendees would have a reasonable familiarity with western literature, history and even some philosophy, but would be less au fait with science and tech. Based on this, I decided to frame my course as a historical / cultural introduction to AI.

–x–

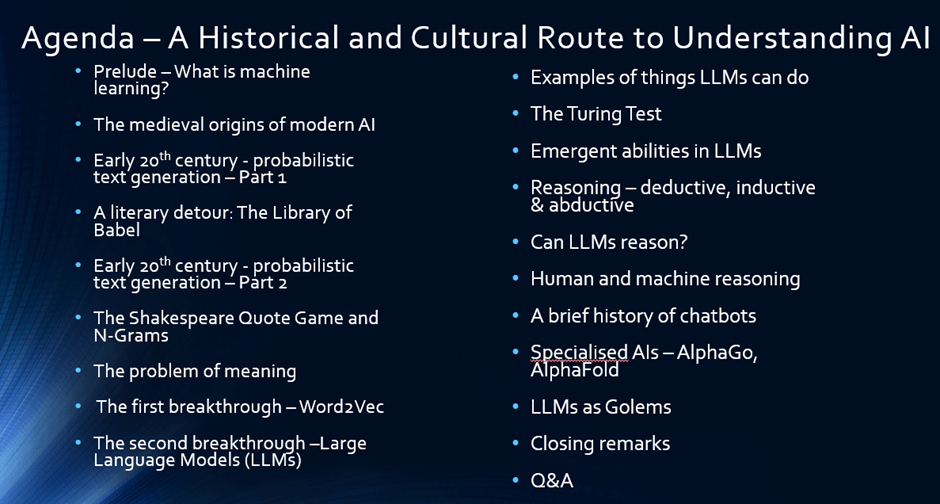

The screenshot below, taken from my slide pack, shows the outline of the course

Here is a walkthrough the agenda, with notes and links to sources:

- I start with a brief introduction to machine learning, drawing largely on the first section of this post.

- The historical sections, which are scattered across the agenda (see figure above), are based on this six part series on the history of natural language processing (NLP) supplemented by material from other sources.

- The history starts with the Jewish mystic Abraham Abulafia and his quest for divine incantations by combining various sacred words. I also introduce the myth of the golem as a metaphor for the double-edgedness of technology, mentioning that I will revisit it at the end of the lecture in the context of AI ethics.

- To introduce the idea of text generation, I use the naïve approach of generating text by randomly combining symbols (alphabet, basic punctuation and spaces), and then demonstrate the futility of this approach using Jorge Luis Borges famous short story, The Library of Babel.

- This naturally leads to more principled approaches based on the actual occurrence of words in text. Here I discuss the pioneering work of Markov and Shannon.

- I then use a “Shakespeare Quote Game” to illustrate the ideas behind next word completion using n-grams. I start with the first word of a Shakespeare quote and ask the audience to guess the quote. With just one word, it is difficult to figure out. However, as I give them more and more consecutive words, the quote becomes more apparent.

- I then illustrate the limitations of n-grams by pointing out the problem of meaning – specifically, the issues associated with synonymy and polysemy. This naturally leads on to Word2Vec, which I describe by illustrating the key idea of how rolling context windows over large corpuses leads to a resolution of the problem. The basic idea here is that instead of defining the meaning of words, we simply consider multiple contexts in which they occur. If done over large and diverse corpuses, this approach can lead to an implicit “understanding” of the meanings of words.

- I also explain the ideas behind word embeddings and vectors using a simple 3d example. Then using vectors, I provide illustrative examples of how the word2vec algorithm captures grammatical and semantic relationships (e.g., country/capital and comparative-superlative forms).

- From word2vec, I segue to transformers and Large Language Models (LLMs) using a hand-wavy discussion. The point here is not so much the algorithm, but how it is (in many ways) a logical extension of the ideas used in early word embedding models. Here I draw heavily on Stephen Wolfram’s excellent essay on ChatGPT.

- I then provide some examples of “good” uses of LLMs – specifically for ideation, explanation and a couple of examples of how I use it in my teaching.

- Any AI course pitched to a general audience must deal with the question of intelligence – what it is, how to determine whether a machine is intelligent etc. To do this, I draw on Alan Turing’s 1950 paper in which he proposes his eponymous test. I illustrate how well LLMs do on the test and ask the question – does this mean LLMs are intelligent? This provokes some debate.

- Instead of answering the question, I suggest that it might be more worthwhile to see if LLMs can display behaviours that one would expect from intelligent beings – for example, the ability to combine different skills or to solve puzzles / math problems using reasoning (see this post for examples of these). Before dealing with the latter, I provide a brief introduction to deductive, inductive and abductive reasoning using examples from popular literature.

- I leave the question of whether LLMs can reason or not unanswered, but I point to a number of different approaches that are popularly used to demonstrate reasoning capabilities of LLMs – e.g. chain of thought prompting. I also make the point that the response obtained from LLMs is heavily dependent on the prompt, and that in many ways, an LLM’s response is a reflection of the intelligence of the user, a point made very nicely by Terrence Sejnowski in this paper.

- The question of whether LLMs can reason is also related to whether we humans think in language. I point out that recent research suggests that we use language to communicate our thinking, but not to think (more on this point here). This poses an interesting question which Cormac McCarthy explored in this article.

- I follow this with a short history of chatbots starting from Eliza to Tay and then to ChatGPT. This material is a bit out of sequence, but I could not find a better place to put it. My discussion draws on the IEEE history mentioned at the start of this section complemented with other sources.

- For completeness, I discuss a couple of specialised AIs – specifically AlphaFold and AlphaGo. My discussion of AlphaFold starts with a brief explanation of the protein folding problem and its significance. I then explain how AlphaFold solved this problem. For AlphaGo, I briefly describe the game of Go, why its considered far more challenging than chess. This is followed by high level explanation of how AlphaGo works. I close this section with a recommendation to watch the brilliant AlphaGo documentary.

- To close, I loop back to where I started – the age old human fascination with creating machines in our own image. The golem myth has a long history which some scholars have traced back to the bible. Today we are a step closer to achieving what medieval mystics yearned for, but it seems we don’t quite know how to deal with the consequences.

I sign off with some open questions around ethics and regulation – areas that are still wide open – as well as some speculations on what comes next, emphasising that I have no crystal ball!

–x–

A couple of points to close this piece.

There was a particularly interesting question from an attendee about whether AI can help solve some of the thorny dilemmas humankind faces today. My response was that these challenges are socially complex – i.e., different groups see these problems differently – so they lack a commonly agreed framing. Consequently, AI is unlikely to be of much help in addressing these challenges. For more on dealing with socially complex or ambiguous problems, see this post and the paper it is based on.

Finally, I’m sure some readers may be wondering how well this approach works. Here are some excerpts from emails I received from few of the attendees:

“What a fascinating three hours with you that was last week. I very much look forward to attending your future talks.”

“I would like to particularly thank you for the AI course that you presented. I found it very informative and very well presented. Look forward to hearing about any further courses in the future.”

“Thank you very much for a stimulating – albeit whirlwind – introduction to the dimensions of artificial intelligence.”

“I very much enjoyed the course. Well worthwhile for me.”

So, yes, I think it worked well and am looking forward to offering it again in 2025.

–x–x–

Copyright Notice: the course design described in this article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/)