Setting up an internal data analytics practice – some thoughts from a wayfarer

Introduction

This year has been hugely exciting so far: I’ve been exploring and playing with various techniques that fall under the general categories of data mining and text analytics. What’s been particularly satisfying is that I’ve been fortunate to find meaningful applications for these techniques within my organization.

Although I have a fair way to travel yet, I’ve learnt that common wisdom about data analytics – especially the stuff that comes from software vendors and high-end consultancies – can be misleading, even plain wrong. Hence this post in which I dispatch some myths and share a few pointers on establishing data analytics capabilities within an organization.

Busting a few myths

Let’s get right to it by taking a critical look at a few myths about setting up an internal data analytics practice.

- Requires high-end technology and a big budget: this myth is easy to bust because I can speak from recent experience. No, you do not need cutting-edge technology or an oversized budget. You can get started for with an outlay of 0$ – yes, that’s right, for free! All you need to is the open-source statistical package R (check out this section of my article on text mining for more on installing and using R) and the willingness to roll-up your sleeves and learn (more about this later). No worries if you prefer to stick with familiar tools – you can even begin with Excel.

- Needs specialist skills: another myth floating around is that you need Phd level knowledge in statistics or applied mathematics to do practical work in analytics. Sorry, but that’s plain wrong. You do need a PhD to do research in the analytics and develop your own algorithms, but not if you want to apply algorithms written by others.Yes, you will need to develop an understanding of the algorithms you plan to use, a feel for how they work and the ability to tell whether the results make sense. There are many good resources that can help you develop these skills – see, for example, the outstanding books by James, Witten, Hastie and Tibshirani and Kuhn and Johnson.

- Must have sponsorship from the top: this one is possibly a little more controversial than the previous two. It could be argued that it is impossible to gain buy in for a new capability without sponsorship from top management. However, in my experience, it is OK to start small by finding potential internal “customers” for analytics services through informal conversations with folks in different functions.I started by having informal conversations with managers in two different areas: IT infrastructure and sales / marketing. I picked these two areas because I knew that they had several gigabytes of under-exploited data – a good bit of it unstructured – and a lot of open questions that could potentially be answered (at least partially) via methods of data and text analytics. It turned out I was right. I’m currently doing a number of proofs of concept and small projects in both these areas. So you don’t need sponsorship from the top as long as you can get buy in from people who have problems they believe you can solve. If you deliver, they may even advocate your cause to their managers.

A caveat is in order at this point: my organization is not the same as yours, so you may well need to follow a different path from mine. Nevertheless, I do believe that it is always possible to find a way to start without needing permission or incurring official wrath. In that spirit, I now offer some suggestions to help kick-start your efforts

Getting started

As the truism goes, the hardest part of any new effort is getting started. The first thing to keep in mind is to start small. This is true even if you have official sponsorship and a king-sized budget. It is very tempting to spend a lot of time garnering management support for investing in high-end technology. Don’t do it! Do the following instead:

- Develop an understanding of the problems faced by people you plan to approach: The best way to do this is to talk to analysts or frontline managers. In my case, I was fortunate to have access to some very savvy analysts in IT service management and marketing who gave me a slew of interesting ideas to pursue. A word of advice: it is best not to talk to senior managers until you have a few concrete results that you can quantify in terms of dollar values.

- Invest time and effort in understanding analytics algorithms and gaining practical experience with them: As mentioned earlier, I started with R – and I believe it is the best choice. Not just because it is free but also because there are a host of packages available to tackle just about any analytics problem you might encounter. There are some excellent free resources available to get you started with R (check out this listing on the r-statistics blog, for example).It is important that you start cutting code as you learn. This will help you build a repertoire of techniques and approaches as you progress. If you get stuck when coding, chances are you will find a solution on the wonderful stackoverflow site.

- Evangelise, evangelise, evangelise: You are, in effect, trying to sell an idea to people within your organization. You therefore have to identify people who might be able to help you and then convince them that your idea has merit. The best way to do the latter is to have concrete examples of problems that you have tackled. This is a chicken-and-egg situation in that you can’t have any examples until you gain support. I got support by approaching people I know well. I found that most – no, all – of them were happy to provide me with interesting ideas and access to their data.

- Begin with small (but real) problems: It is important to start with the “low-hanging fruit” – the problems that would take the least effort to solve. However, it is equally important to address real problems, i.e. those that matter to someone.

- Leverage your organisation’s existing data infrastructure: From what I’ve written thus far, I may have given you the impression that the tools of data analytics stand separate from your existing data infrastructure. Nothing could be further from the truth. In reality, I often do the initial work (basic preprocessing and exploratory analysis) using my organisation’s relational database infrastructure. Relational databases have sophisticated analytical extensions to SQL as well as efficient bulk data cleansing and transport facilities. Using these make good sense, particularly if your R installation is on a desktop or laptop computer as it is in my case. Moreover, many enterprise database vendors now offer add-on options that integrate R with their products. This gives you the best of both worlds – relational and analytical capabilities on an enterprise-class platform.

- Build relationships with the data management team: Remember the work you are doing falls under the ambit of the group that is officially responsible for managing data in your organization. It is therefore important that you keep them informed of what you’re doing. Sooner or later your paths will cross, and you want to be sure that there are no nasty surprises (for either side!) at that point. Moreover, if you build connections with them early, you may even find that the data management team supports your efforts.

Having waxed verbose, I should mention that my effort is work in progress and I do not know where it will lead. Nevertheless, I offer these suggestions as a wayfarer who is considerably further down the road from where he started.

Parting thoughts

You may have noticed that I’ve refrained from using the overused and over-hyped term “Big Data” in this piece. This is deliberate. Indeed, the techniques I have been using have nothing to do with the size of the datasets. To be honest, I’ve applied them to datasets ranging from a few thousand to a few hundred thousand records, both of which qualify as Very Small Data in today’s world.

Your vendor will be only too happy to sell you Big Data infrastructure that will set you back a good many dollars. However, the chances are good that you do not need it right now. You’ll be much better off going back to them after you hit the limits of your current data processing infrastructure. Moreover, you’ll also be better informed about your needs then.

You may also be wondering why I haven’t said much about the composition of the analytics team (barring the point about not needing PhD statisticians) and how it should be organized. The reason I haven’t done so is that I believe the right composition and organizational structure will emerge from the initial projects done and feedback received from internal customers. The resulting structure will be better suited to the organization than one that is imposed upfront. Long time readers of this blog might recognize this as a tenet of emergent design.

Finally, I should reiterate that my efforts are still very much in progress and I know not where they will lead. However, even if they go nowhere, I would have learnt something about my organization and picked up a useful, practical skill. And that is good enough for me.

From inactivism to interactivism – managerial attitudes to planning

Introduction

Managers display a range of attitudes towards planning for the future. In an essay entitled Systems, Messes and Interactive Planning, the management guru/philosopher Russell Ackoff classified attitudes to organizational planning into four distinct types which I describe in detail below. I suspect you may recognise examples of each of these in your organisation…indeed, you might even see shades of yourself 🙂

Inactivism

This attitude, as its name suggests, is characterized by a lack of meaningful action. Inactivism is often displayed by managers in organisations that favour the status quo. These organisations are happy with the way things are, and therefore see no need to change. However, lack of meaningful action does not mean lack of action. On the contrary, it often takes a great deal of effort to fend off change and keep things the way they are. As Ackoff states:

Inactive organizations require a great deal of activity to keep changes from being made. They accomplish nothing in a variety of ways. First, they require that all important decisions be made “at the top.” The route to the top is deliberately designed like an obstacle course. This keeps most recommendations for change from ever getting there. Those that do are likely to have been delayed enough to make them irrelevant when they reach their destination. Those proposals that reach the top are likely to be farther delayed, often by being sent back down or out for modification or evaluation. The organization thus behaves like a sponge and is about as active…

The inactive manager spends a lot of time and effort in ensuring that things remain the way they are. Hence they act only when a stituation forces them to. Ackoff puts it in his inimitable way by stating that, “Inactivist managers tend to want what they get rather than get what they want.”

Reactivism

Reactivist managers are a step worse than inactivists because they believe that disaster is already upon them. This is the type of manager who hankers after the “golden days of yore when things were much better than they are today.” As a result of their deep unease of where they are now, they may try to undo the status quo. As Ackoff points out, unlike inactivists, reactivists do not ride the tide but try to swim against it.

Typically reactivist managers are wary of technology and new concepts. Moreover, they tend to give more importance to seniority and experience rather than proven competence. They also tend to be fans of simplistic solutions to complex problems…like “solving” the problem of a behind-schedule software project by throwing more people at it.

Preactivism

Preactivists are the opposite of reactivists in that they believe the future is going to be better than the past. Consequently, their efforts are geared towards understanding what the future will look like and how they can prepare for it. Typically, preactive managers are concerned with facts, figures and forecasts; they are firm believers in scientific planning methods that they have learnt in management schools. As such, one might say that this is the most common species of manager in present day organisations. Those who are not natural preactivists will fly the preactivist flag when they’re asked for their opinions by their managers because it’s the expected answer.

A key characteristic of preactivist managers is that they tend to revel in creating plans rather than implementing them. As Ackoff puts it, “Preactivists see planning as a sequence of discrete steps which terminate with acceptance or rejection of their plans. What happens to their plans is the responsibility of others.”

Interactivism

Interactivists planners are not satisfied with the present, but unlike reactivists or preactivists, they do not hanker for the past, nor do they believe the future is automatically going to be better. They do want to make things better than they were or currently are, but they are continually adjusting their plans for the future by learning from and responding to events. In short, they believe they can shape the future by their actions.

Experimentation is the hallmark of interactivists. They are willing to try different approaches and learn from them. Although they believe in learning by experience, they do not want to wait for experiences to happen; they would rather induce them by (often small-scale) experimentation.

Ackoff labels interactivists as idealisers – people who pursue ideals they know cannot be achieved, but can be approximated or even reformulated in the light of new knowledge. As he puts it:

They treat ideals as relative absolutes: ultimate objectives whose formulation depends on our current knowledge and understanding of ourselves and our environment. Therefore, they require continuous reformulation in light of what we learn from approaching them.

To use a now fashionable term, interactivists are intrapreneurs.

Discussion

Although Ackoff shows a clear bias towards interactivists in his article, he does mention that specific situations may call for other types of planners. As he puts it:

Despite my obvious bias in my characterization of these four postures, there are circumstances in which each is most appropriate. Put simply, if the internal and external dynamics of a system (the tide) are taking one where one wants to go and are doing so quickly enough, inactivism is appropriate. If the direction of change is right but the movement is too slow, preactivism is appropriate. If the change is taking one where one does not want to go and one prefers to stay where one is or was, reactivism is appropriate. However, if one is not willing to settle for the past, the present or the future that appears likely now, interactivism is appropriate.

The key point he makes is that inactivists and preactivists treat planning as a ritual because they see the future as something they cannot change. They can only plan for it (and hope for the best). Interactivists, on the other hand, look for opportunities to influence events and thus potentially change the future. Although both preactivists and interactivists are forward-looking, interactivists tend to be long-term thinkers as compared to preactivists who are more concerned about the short to medium term future.

Conclusion

Ackoff’s classification of planners in organisations is interesting because it highlights the kind of future-focused attitude that managers ought to take. The sad fact, though, is that a significant number of managers are myopic preactivists, focused on this year’s performance targets rather than what their organisations might look like five or even ten years down the line. This is not the fault of individuals, though. The blame for the undue prevalence of myopic preactivism can be laid squarely on the deep-seated management dogma that rewards short-termism.

A gentle introduction to cluster analysis using R

Introduction

Welcome to the second part of my introductory series on text analysis using R (the first article can be accessed here). My aim in the present piece is to provide a practical introduction to cluster analysis. I’ll begin with some background before moving on to the nuts and bolts of clustering. We have a fair bit to cover, so let’s get right to it.

A common problem when analysing large collections of documents is to categorize them in some meaningful way. This is easy enough if one has a predefined classification scheme that is known to fit the collection (and if the collection is small enough to be browsed manually). One can then simply scan the documents, looking for keywords appropriate to each category and classify the documents based on the results. More often than not, however, such a classification scheme is not available and the collection too large. One then needs to use algorithms that can classify documents automatically based on their structure and content.

The present post is a practical introduction to a couple of automatic text categorization techniques, often referred to as clustering algorithms. As the Wikipedia article on clustering tells us:

Cluster analysis or clustering is the task of grouping a set of objects in such a way that objects in the same group (called a cluster) are more similar (in some sense or another) to each other than to those in other groups (clusters).

As one might guess from the above, the results of clustering depend rather critically on the method one uses to group objects. Again, quoting from the Wikipedia piece:

Cluster analysis itself is not one specific algorithm, but the general task to be solved. It can be achieved by various algorithms that differ significantly in their notion of what constitutes a cluster and how to efficiently find them. Popular notions of clusters include groups with small distances [Note: we’ll use distance-based methods] among the cluster members, dense areas of the data space, intervals or particular statistical distributions [i.e. distributions of words within documents and the entire collection].

…and a bit later:

…the notion of a “cluster” cannot be precisely defined, which is one of the reasons why there are so many clustering algorithms. There is a common denominator: a group of data objects. However, different researchers employ different cluster models, and for each of these cluster models again different algorithms can be given. The notion of a cluster, as found by different algorithms, varies significantly in its properties. Understanding these “cluster models” is key to understanding the differences between the various algorithms.

An upshot of the above is that it is not always straightforward to interpret the output of clustering algorithms. Indeed, we will see this in the example discussed below.

With that said for an introduction, let’s move on to the nut and bolts of clustering.

Preprocessing the corpus

In this section I cover the steps required to create the R objects necessary in order to do clustering. It goes over territory that I’ve covered in detail in the first article in this series – albeit with a few tweaks, so you may want to skim through even if you’ve read my previous piece.

To begin with I’ll assume you have R and RStudio (a free development environment for R) installed on your computer and are familiar with the basic functionality in the text mining ™ package. If you need help with this, please look at the instructions in my previous article on text mining.

As in the first part of this series, I will use 30 posts from my blog as the example collection (or corpus, in text mining-speak). The corpus can be downloaded here. For completeness, I will run through the entire sequence of steps – right from loading the corpus into R, to running the two clustering algorithms.

Ready? Let’s go…

The first step is to fire up RStudio and navigate to the directory in which you have unpacked the example corpus. Once this is done, load the text mining package, tm. Here’s the relevant code (Note: a complete listing of the code in this article can be accessed here):

[1] “C:/Users/Kailash/Documents”

#set working directory – fix path as needed!

setwd(“C:/Users/Kailash/Documents/TextMining”)

#load tm library

library(tm)

Loading required package: NLP

Note: R commands are in blue, output in black or red; lines that start with # are comments.

If you get an error here, you probably need to download and install the tm package. You can do this in RStudio by going to Tools > Install Packages and entering “tm”. When installing a new package, R automatically checks for and installs any dependent packages.

The next step is to load the collection of documents into an object that can be manipulated by functions in the tm package.

docs <- Corpus(DirSource("C:/Users/Kailash/Documents/TextMining"))

#inspect a particular document

writeLines(as.character(docs[[30]]))

…

The next step is to clean up the corpus. This includes things such as transforming to a consistent case, removing non-standard symbols & punctuation, and removing numbers (assuming that numbers do not contain useful information, which is the case here):

docs <- tm_map(docs,content_transformer(tolower))

#remove potentiallyy problematic symbols

toSpace <- content_transformer(function(x, pattern) { return (gsub(pattern, " ", x))})

docs <- tm_map(docs, toSpace, "-")

docs <- tm_map(docs, toSpace, ":")

docs <- tm_map(docs, toSpace, "‘")

docs <- tm_map(docs, toSpace, "•")

docs <- tm_map(docs, toSpace, "• ")

docs <- tm_map(docs, toSpace, " -")

docs <- tm_map(docs, toSpace, "“")

docs <- tm_map(docs, toSpace, "”")

#remove punctuation

docs <- tm_map(docs, removePunctuation)

#Strip digits

docs <- tm_map(docs, removeNumbers)

Note: please see my previous article for more on content_transformer and the toSpace function defined above.

Next we remove stopwords – common words (like “a” “and” “the”, for example) and eliminate extraneous whitespaces.

docs <- tm_map(docs, removeWords, stopwords("english"))

#remove whitespace

docs <- tm_map(docs, stripWhitespace)

writeLines(as.character(docs[[30]]))

flexibility eye beholder action increase organisational flexibility say redeploying employees likely seen affected move constrains individual flexibility dual meaning characteristic many organizational platitudes excellence synergy andgovernance interesting exercise analyse platitudes expose difference espoused actual meanings sign wishing many hours platitude deconstructing fun

At this point it is critical to inspect the corpus because stopword removal in tm can be flaky. Yes, this is annoying but not a showstopper because one can remove problematic words manually once one has identified them – more about this in a minute.

Next, we stem the document – i.e. truncate words to their base form. For example, “education”, “educate” and “educative” are stemmed to “educat.”:

Stemming works well enough, but there are some fixes that need to be done due to my inconsistent use of British/Aussie and US English. Also, we’ll take this opportunity to fix up some concatenations like “andgovernance” (see paragraph printed out above). Here’s the code:

docs <- tm_map(docs, content_transformer(gsub), pattern = "organis", replacement = "organ")

docs <- tm_map(docs, content_transformer(gsub), pattern = "andgovern", replacement = "govern")

docs <- tm_map(docs, content_transformer(gsub), pattern = "inenterpris", replacement = "enterpris")

docs <- tm_map(docs, content_transformer(gsub), pattern = "team-", replacement = "team")

The next step is to remove the stopwords that were missed by R. The best way to do this for a small corpus is to go through it and compile a list of words to be eliminated. One can then create a custom vector containing words to be removed and use the removeWords transformation to do the needful. Here is the code (Note: + indicates a continuation of a statement from the previous line):

+ "also","howev","tell","will",

+ "much","need","take","tend","even",

+ "like","particular","rather","said",

+ "get","well","make","ask","come","end",

+ "first","two","help","often","may",

+ "might","see","someth","thing","point",

+ "post","look","right","now","think","’ve ",

+ "’re ")

#remove custom stopwords

docs <- tm_map(docs, removeWords, myStopwords)

Again, it is a good idea to check that the offending words have really been eliminated.

The final preprocessing step is to create a document-term matrix (DTM) – a matrix that lists all occurrences of words in the corpus. In a DTM, documents are represented by rows and the terms (or words) by columns. If a word occurs in a particular document n times, then the matrix entry for corresponding to that row and column is n, if it doesn’t occur at all, the entry is 0.

Creating a DTM is straightforward– one simply uses the built-in DocumentTermMatrix function provided by the tm package like so:

#print a summary

dtmNon-/sparse entries: 13312/110618

Sparsity : 89%

Maximal term length: 48

Weighting : term frequency (tf)

This brings us to the end of the preprocessing phase. Next, I’ll briefly explain how distance-based algorithms work before going on to the actual work of clustering.

An intuitive introduction to the algorithms

As mentioned in the introduction, the basic idea behind document or text clustering is to categorise documents into groups based on likeness. Let’s take a brief look at how the algorithms work their magic.

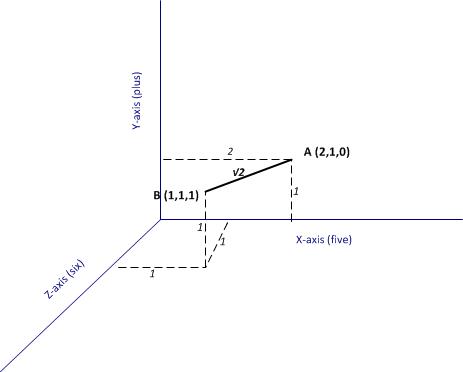

Consider the structure of the DTM. Very briefly, it is a matrix in which the documents are represented as rows and words as columns. In our case, the corpus has 30 documents and 4131 words, so the DTM is a 30 x 4131 matrix. Mathematically, one can think of this matrix as describing a 4131 dimensional space in which each of the words represents a coordinate axis and each document is represented as a point in this space. This is hard to visualise of course, so it may help to illustrate this via a two-document corpus with only three words in total.

Consider the following corpus:

Document A: “five plus five”

Document B: “five plus six”

These two documents can be represented as points in a 3 dimensional space that has the words “five” “plus” and “six” as the three coordinate axes (see figure 1).

Now, if each of the documents can be thought of as a point in a space, it is easy enough to take the next logical step which is to define the notion of a distance between two points (i.e. two documents). In figure 1 the distance between A and B (which I denote as )is the length of the line connecting the two points, which is simply, the sum of the squares of the differences between the coordinates of the two points representing the documents.

Generalising the above to the 4131 dimensional space at hand, the distance between two documents (let’s call them X and Y) have coordinates (word frequencies) and

, then one can define the straight line distance (also called Euclidean distance)

between them as:

It should be noted that the Euclidean distance that I have described is above is not the only possible way to define distance mathematically. There are many others but it would take me too far afield to discuss them here – see this article for more (and don’t be put off by the term metric, a metric in this context is merely a distance)

What’s important here is the idea that one can define a numerical distance between documents. Once this is grasped, it is easy to understand the basic idea behind how (some) clustering algorithms work – they group documents based on distance-related criteria. To be sure, this explanation is simplistic and glosses over some of the complicated details in the algorithms. Nevertheless it is a reasonable, approximate explanation for what goes on under the hood. I hope purists reading this will agree!

Finally, for completeness I should mention that there are many clustering algorithms out there, and not all of them are distance-based.

Hierarchical clustering

The first algorithm we’ll look at is hierarchical clustering. As the Wikipedia article on the topic tells us, strategies for hierarchical clustering fall into two types:

Agglomerative: where we start out with each document in its own cluster. The algorithm iteratively merges documents or clusters that are closest to each other until the entire corpus forms a single cluster. Each merge happens at a different (increasing) distance.

Divisive: where we start out with the entire set of documents in a single cluster. At each step the algorithm splits the cluster recursively until each document is in its own cluster. This is basically the inverse of an agglomerative strategy.

The algorithm we’ll use is hclust which does agglomerative hierarchical clustering. Here’s a simplified description of how it works:

- Assign each document to its own (single member) cluster

- Find the pair of clusters that are closest to each other and merge them. So you now have one cluster less than before.

- Compute distances between the new cluster and each of the old clusters.

- Repeat steps 2 and 3 until you have a single cluster containing all documents.

We’ll need to do a few things before running the algorithm. Firstly, we need to convert the DTM into a standard matrix which can be used by dist, the distance computation function in R (the DTM is not stored as a standard matrix). We’ll also shorten the document names so that they display nicely in the graph that we will use to display results of hclust (the names I have given the documents are just way too long). Here’s the relevant code:

m <- as.matrix(dtm)

#write as csv file (optional)

write.csv(m,file="dtmEight2Late.csv")

#shorten rownames for display purposes

rownames(m) <- paste(substring(rownames(m),1,3),rep("..",nrow(m)),

+ substring(rownames(m), nchar(rownames(m))-12,nchar(rownames(m))-4))

#compute distance between document vectors

d <- dist(m)

Next we run hclust. The algorithm offers several options check out the documentation for details. I use a popular option called Ward’s method – there are others, and I suggest you experiment with them as each of them gives slightly different results making interpretation somewhat tricky (did I mention that clustering is as much an art as a science??). Finally, we visualise the results in a dendogram (see Figure 2 below).

#run hierarchical clustering using Ward’s method

groups <- hclust(d,method="ward.D")

#plot dendogram, use hang to ensure that labels fall below tree

plot(groups, hang=-1)

A few words on interpreting dendrograms for hierarchical clusters: as you work your way down the tree in figure 2, each branch point you encounter is the distance at which a cluster merge occurred. Clearly, the most well-defined clusters are those that have the largest separation; many closely spaced branch points indicate a lack of dissimilarity (i.e. distance, in this case) between clusters. Based on this, the figure reveals that there are 2 well-defined clusters – the first one consisting of the three documents at the right end of the cluster and the second containing all other documents. We can display the clusters on the graph using the rect.hclust function like so:

rect.hclust(groups,2)

The result is shown in the figure below.

The figures 4 and 5 below show the grouping for 3, and 5 clusters.

I’ll make just one point here: the 2 cluster grouping seems the most robust one as it happens at large distance, and is cleanly separated (distance-wise) from the 3 and 5 cluster grouping. That said, I’ll leave you to explore the ins and outs of hclust on your own and move on to our next algorithm.

K means clustering

In hierarchical clustering we did not specify the number of clusters upfront. These were determined by looking at the dendogram after the algorithm had done its work. In contrast, our next algorithm – K means – requires us to define the number of clusters upfront (this number being the “k” in the name). The algorithm then generates k document clusters in a way that ensures the within-cluster distances from each cluster member to the centroid (or geometric mean) of the cluster is minimised.

Here’s a simplified description of the algorithm:

- Assign the documents randomly to k bins

- Compute the location of the centroid of each bin.

- Compute the distance between each document and each centroid

- Assign each document to the bin corresponding to the centroid closest to it.

- Stop if no document is moved to a new bin, else go to step 2.

An important limitation of the k means method is that the solution found by the algorithm corresponds to a local rather than global minimum (this figure from Wikipedia explains the difference between the two in a nice succinct way). As a consequence it is important to run the algorithm a number of times (each time with a different starting configuration) and then select the result that gives the overall lowest sum of within-cluster distances for all documents. A simple check that a solution is robust is to run the algorithm for an increasing number of initial configurations until the result does not change significantly. That said, this procedure does not guarantee a globally optimal solution.

I reckon that’s enough said about the algorithm, let’s get on with it using it. The relevant function, as you might well have guessed is kmeans. As always, I urge you to check the documentation to understand the available options. We’ll use the default options for all parameters excepting nstart which we set to 100. We also plot the result using the clusplot function from the cluster library (which you may need to install. Reminder you can install packages via the Tools>Install Packages menu in RStudio)

kfit <- kmeans(d, 2, nstart=100)

#plot – need library cluster

library(cluster)

clusplot(as.matrix(d), kfit$cluster, color=T, shade=T, labels=2, lines=0)

The plot is shown in Figure 6.

The cluster plot shown in the figure above needs a bit of explanation. As mentioned earlier, the clustering algorithms work in a mathematical space whose dimensionality equals the number of words in the corpus (4131 in our case). Clearly, this is impossible to visualize. To handle this, mathematicians have invented a dimensionality reduction technique called Principal Component Analysis which reduces the number of dimensions to 2 (in this case) in such a way that the reduced dimensions capture as much of the variability between the clusters as possible (and hence the comment, “these two components explain 69.42% of the point variability” at the bottom of the plot in figure 6)

(Aside Yes I realize the figures are hard to read because of the overly long names, I leave it to you to fix that. No excuses, you know how…:-))

Running the algorithm and plotting the results for k=3 and 5 yields the figures below.

Choosing k

Recall that the k means algorithm requires us to specify k upfront. A natural question then is: what is the best choice of k? In truth there is no one-size-fits-all answer to this question, but there are some heuristics that might sometimes help guide the choice. For completeness I’ll describe one below even though it is not much help in our clustering problem.

In my simplified description of the k means algorithm I mentioned that the technique attempts to minimise the sum of the distances between the points in a cluster and the cluster’s centroid. Actually, the quantity that is minimised is the total of the within-cluster sum of squares (WSS) between each point and the mean. Intuitively one might expect this quantity to be maximum when k=1 and then decrease as k increases, sharply at first and then less sharply as k reaches its optimal value.

The problem with this reasoning is that it often happens that the within cluster sum of squares never shows a slowing down in decrease of the summed WSS. Unfortunately this is exactly what happens in the case at hand.

I reckon a picture might help make the above clearer. Below is the R code to draw a plot of summed WSS as a function of k for k=2 all the way to 29 (1-total number of documents):

#look for “elbow” in plot of summed intra-cluster distances (withinss) as fn of k

wss <- 2:29

for (i in 2:29) wss[i] <- sum(kmeans(d,centers=i,nstart=25)$withinss)

plot(2:29, wss[2:29], type="b", xlab="Number of Clusters",ylab="Within groups sum of squares")

…and the figure below shows the resulting plot.

The plot clearly shows that there is no k for which the summed WSS flattens out (no distinct “elbow”). As a result this method does not help. Fortunately, in this case one can get a sensible answer using common sense rather than computation: a choice of 2 clusters seems optimal because both algorithms yield exactly the same clusters and show the clearest cluster separation at this point (review the dendogram and cluster plots for k=2).

The meaning of it all

Now I must acknowledge an elephant in the room that I have steadfastly ignored thus far. The odds are good that you’ve seen it already….

It is this: what topics or themes do the (two) clusters correspond to?

Unfortunately this question does not have a straightforward answer. Although the algorithms suggest a 2-cluster grouping, they are silent on the topics or themes related to these. Moreover, as you will see if you experiment, the results of clustering depend on:

- The criteria for the construction of the DTM (see the documentation for DocumentTermMatrix for options).

- The clustering algorithm itself.

Indeed, insofar as clustering is concerned, subject matter and corpus knowledge is the best way to figure out cluster themes. This serves to reinforce (yet again!) that clustering is as much an art as it is a science.

In the case at hand, article length seems to be an important differentiator between the 2 clusters found by both algorithms. The three articles in the smaller cluster are in the top 4 longest pieces in the corpus. Additionally, the three pieces are related to sensemaking and dialogue mapping. There are probably other factors as well, but none that stand out as being significant. I should mention, however, that the fact that article length seems to play a significant role here suggests that it may be worth checking out the effect of scaling distances by word counts or using other measures such a cosine similarity – but that’s a topic for another post! (Note added on Dec 3 2015: check out my article on visualizing relationships between documents using network graphs for a detailed discussion on cosine similarity)

The take home lesson is that is that the results of clustering are often hard to interpret. This should not be surprising – the algorithms cannot interpret meaning, they simply chug through a mathematical optimisation problem. The onus is on the analyst to figure out what it means…or if it means anything at all.

Conclusion

This brings us to the end of a long ramble through clustering. We’ve explored the two most common methods: hierarchical and k means clustering (there are many others available in R, and I urge you to explore them). Apart from providing the detailed steps to do clustering, I have attempted to provide an intuitive explanation of how the algorithms work. I hope I have succeeded in doing so. As always your feedback would be very welcome.

Finally, I’d like to reiterate an important point: the results of our clustering exercise do not have a straightforward interpretation, and this is often the case in cluster analysis. Fortunately I can close on an optimistic note. There are other text mining techniques that do a better job in grouping documents based on topics and themes rather than word frequencies alone. I’ll discuss this in the next article in this series. Until then, I wish you many enjoyable hours exploring the ins and outs of clustering.

Note added on September 29th 2015:

If you liked this article, you might want to check out its sequel – an introduction to topic modeling.