Posts Tagged ‘Organizational Change’

On the velocity of organisational change

Introduction

Management consultants and gurus emphasise the need for organisations to adapt to an ever-changing environment. Although this advice is generally sound, change initiatives continue to falter, stumble and even fail outright. There are many reasons for this. One is that the unintended consequences of change may overshadow its anticipated benefits, a point that gurus/consultants are careful to hide when selling their trademarked change formulas. Another is that a proposed change may be ill-conceived (though it must be admitted that this often becomes clear only after a change has been implemented). That said, many changes initiatives that are well thought through still end up failing. In this post I discuss one of the main reasons why this happens and what one can do to address it.

Change velocity

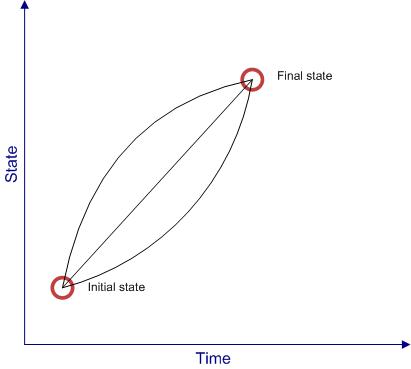

Let’s begin with a two dimensional grid as in Figure 1, with time on the horizontal axis and the state of the organisation along vertical axis (before going any further I should also mention that this model is grossly simplified – among other things it assumes that the state of the organisation can be defined by a single variable). We can represent the current state of a hypothetical organisation by the point marked as the “Initial state” in Figure 1.

Now imagine that the powers that be have decided that the organisation needs to change. Further, let’s imagine (…and this is hard) that they have good advisors who know what the organisation should look like after the change. This tells us the position of the final state along the vertical axis.

To plot the final state of the organisation on our grid we also need to fix its position along the horizontal (time) dimension- that is, we need to know by when the change will be implemented. The powers that be are so delighted by the consultants’ advice that they want the changes to be rolled out asap (sound familiar?). Plucking a deadline out of thin air, they decree it must be done by within a certain fixed (short!) period of time.

The end state of the organisation is thus represented by the point marked as the final state in Figure 1.

Let’s now consider some of the paths that by which the organisation can get from initial to the final state. Figure 2 shows some possible change paths – a concave curve (top), a straight line (middle) and a convex curve (bottom).

Insofar as this discussion is concerned, the important difference between these three curves is that each them describes a different “rate of change of change.” This is a rather clumsy and confusing term because the word change is used in two different senses. To simplify matters and avoid confusion, I will henceforth refer to it as the velocity of organisational change or simply, the velocity of change. The important point to note is that the velocity of change at any point along a change path is given by the steepness of the curve at that point.

Now for the paths shown in Figure 2:

- The concave path describes a situation in which the velocity of change is greatest at the start and then decreases as time goes on (i.e. the path is steepest at the start and then flattens out)

- The straight line path describes a situation in which the velocity of change is constant (i.e. the steepness is constant)

- The convex path describes a situation in which the velocity of change is smallest at the start and then increases with time. (i.e. the path starts out flat and then becomes steeper as the end state is approached)

To keep things simple I’ll assume that the change in our fictitious organisation happens at a constant velocity – i.e it can be described by the straight line. This is an oversimplification, of course, but not one that materially affects the conclusion.

What is clear is that by mandating the end date, the powers be have committed the organisation to a particular velocity of change. The key question is whether the required velocity is achievable and, more important, sustainable over the entire period in which the change is to be implemented.

An achievable and sustainable change velocity

Figuring out an achievable and sustainable velocity of change is no easy matter. It requires a deep understanding of how the organisation works at a detailed level. This knowledge is held by key people who work at the coalface of the organisation, and it is only by identifying and talking to them that management can get a good understanding of how long their proposed changes may take to implement and thus the actual path (i.e. curve) from the initial to the final state. Problem is, this is rarely done.

The foregoing discussion suggests a rather obvious way to address the issue –reduce the velocity of change or, to put it in simple terms, slow the pace of change. There are two benefits that come from doing this:

- First, the obvious one – a slower pace means that it is less likely that people will be overwhelmed by the work involved in making the change happen.

- The organisation can make changes incrementally, observe its effects and decide on next steps based on actual observations rather than wishful thinking.

- The organisation has enough time to absorb and digest the changes before the next instalment comes through. Implementing changes too fast will only result in organisational indigestion.

Problem is, the only way to do this is to allow a longer time for the change to be implemented (see Figure 3). The longer the time allotted, the lower the velocity of change (or steepness) and the more likely it is that the velocity will be achievable and sustainable.

Of course, there is nothing radical or new about this, It is intuitively obvious that the more time one allows for a change to be implemented, the more likely it is to be successful. Proponents of iterative and incremental change have been saying this for years – Barbara Czarniawska’s wonderful book, A Theory of Organizing, for example.

Summarising

Many well-intentioned organisational change initiatives fail because they are implemented in too short a time. When changes are implemented are too fast, there is no time to reflect on what’s happening and/or fix problems. The way to avoid this is clear: slow down. As in a real journey, this will give you time to appreciate the scenery and, more important, you’ll be better placed to deal with unforeseen events and hazards.

On the shortcomings of cause-effect based models in management

Introduction

Business schools perpetuate the myth that the outcomes of changes in organizations can be managed using models that are rooted in the scientific-rational mode of enquiry. In essence, such models assume that all important variables that affect an outcome (i.e. causes) are known and that the relationship between these variables and the outcomes (i.e. effects) can be represented accurately by simple models. This is the nature of explanation in the hard sciences such as physics and is pretty much the official line adopted by mainstream management research and teaching – a point I have explored at length in an earlier post.

Now it is far from obvious that a mode of explanation that works for physics will also work for management. In fact, there is enough empirical evidence that most cause-effect based management models do not work in the real world. Many front-line employees and middle managers need no proof because they have likely lived through failures of such models in their organisations- for example, when the unintended consequences of organisational change swamp its intended (or predicted) effects.

In this post I look at the missing element in management models – human intentions – drawing on this paper by Sumantra Ghoshal which explores three different modes of explanation that were elaborated by Jon Elster in this book. My aim in doing this is to highlight the key reason why so many management initiatives fail.

Types of explanations

According to Elster, the nature of what we can reasonably expect from an explanation differs in the natural and social sciences. Furthermore, within the natural sciences, what constitutes an explanation differs in the physical and biological sciences.

Let’s begin with the difference between physics and biology first.

The dominant mode of explanation in physics (and other sciences that deal with inanimate matter) is causal – i.e. it deals with causes and effects as I have described in the introduction. For example, the phenomenon of gravity is explained as being caused by the presence of matter, the precise relationship being expressed via Newton’s Law of Gravitation (or even more accurately, via Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity). Gravity is “explained” by these models because they tell us that it is caused by the presence of matter. More important, if we know the specific configuration of matter in a particular problem, we can accurately predict the effects of gravity – our success in sending unmanned spacecraft to Saturn or Mars depends rather crucially on this.

In biology, the nature of explanation is somewhat different. When studying living creatures we don’t look for causes and effects. Instead we look for explanations based on function. For example, zoologists do not need to ask how amphibians came to have webbed feet; it is enough for them to know that webbed feet are an adaptation that affords amphibians a survival advantage. They need look no further than this explanation because it is consistent with the Theory of Evolution – that changes in organisms occur by chance, and those that survive do so because they offer the organism a survival advantage. There is no need to look for a deeper explanation in terms of cause and effect.

In social sciences the situation is very different indeed. The basic unit of explanation in the social sciences is the individual. But an individual is different from an inanimate object or even a non-human organism that reacts to specific stimuli in predictable ways. The key difference is that human actions are guided by intentions, and any explanation of social phenomena ought to start from these intentions.

For completeness I should mention that functional and causal explanations are sometimes possible within the social sciences and management. Typically functional explanations are possible in tightly controlled environments. For example, the behaviour and actions of people working within large bureaucracies or assembly lines can be understood on the basis of function. Causal explanations are even rarer, because they are possible only when focusing on the collective behaviour of large, diverse populations in which the effects of individual intentions are swamped by group diversity. In such special cases, people can indeed be treated as molecules or atoms.

Implications for management

There a couple of interesting implications of restoring intentionality to its rightful place in management studies.

Firstly, as Ghoshal states in his paper:

Management theories at present are overwhelmingly causal or functional in their modes of explanation. Ethics or morality, however, are mental phenomena. As a result they have had to be excluded from our theories and from the practices that such theories have shaped. In other words, a precondition for making business studies a science as well as a consequence of the resulting belief in determinism has been the explicit denial of any role of moral or ethical considerations in the practice of management

Present day management studies exclude considerations of morals and ethics, except, possibly, as a separate course that has little relation to the other subjects that form a part of the typical business school curriculum. Recognising the role of intentionality restores ethical and moral considerations where they belong – on the centre-stage of management theory and practice.

Secondly, recognizing the role of intentions in determining peoples’ actions helps us see that organizational changes that “start from where people are” have a much better chance of succeeding than those that are initiated top-down with little or no consultation with rank and file employees. Unfortunately the large majority of organizational change initiatives still start from the wrong place – the top.

Summing up

Most management practices that are taught in business schools and practiced by the countless graduates of these programs are rooted in the belief that certain actions (causes) will lead to specific, desired outcomes (effects). In this article I have discussed how explanations based on cause-effect models, though good for understanding the behaviour of molecules and possibly even mice, are misleading in the world of humans. To achieve sustainable and enduring outcomes in organisation one has to start from where people are, and to do that one has to begin by taking their opinions and aspirations seriously.

The paradoxes of organisational change

Introduction

It is a truism that organisations are in a constant state of change. It seems that those who run organisations are rarely satisfied with the status quo, and their unending quest to improve products, performance, sales or whatever makes change an inescapable fact of organizational life.

Many decision makers and managers who implement change take a somewhat naïve view of the process: they focus on what they want rather than all the things that could happen. This is understandable because change projects are initiated and plans made when all the nitty-gritty details that may cause problems are not yet in view. Given that it is impossible to surface all significant details at the start. is there anything that decision-makers and managers can do to address the inevitable ambiguity of change?

One of the underappreciated facets of organizational change is that it is inherently paradoxical. For example, although it is well known that such changes inevitably have unintended consequences that are harmful, most organisations continue to implement change initiatives in a manner that assumes complete controllability with the certainty of achieving solely beneficial outcomes.

It is my contention that an understanding of the paradoxes that operate in the day-to-day work of change might help managers in developing a more realistic picture of how a change initiative might unfold and some of the problems that they might encounter. In this post, I look at the paradoxes of organizational change drawing on a paper entitled, The social construction of organizational change paradoxes.

Paradoxes are social constructs

More often than not, the success of an organizational change hinges on the willingness of people to change their attitudes, behaviour and work practices. In view of this it is no surprise that many of the difficulties of organizational change have social origins.

Change makes conflicting demands on people: for example, managerial rhetoric about the need to improve efficiency is often accompanied by actions that actually decrease it. As a result, many of the obstacles to change arise from elements that seem sensible when considered individually, but are conflicting and contradictory when taken together. This results in paradox. As the authors of the paper state:

We propose that paradox is constructed when elements of our thoughts, actions and emotions that seemed logical when considered in isolation, are juxtaposed, appearing mutually exclusive. The result is often an experience of absurdity or paralysis.

Again it is important to note that change-related paradoxes have social origins – they are caused by the actions of certain individual or groups and their effects or perceived effects on others.

Paradoxes of organizational change

The authors describe three paradoxes of organizational change: paradoxes of performing, belonging and organizing. I describe each of these below, but before I do so, it is worth noting that paradoxes are often exacerbated by people’s reactions to them. In particular, those affected by a change tend to interpret it using frames of reference that accentuate negative effects. For example, employees may view a change initiative as a threat rather than an opportunity to improve performance. Paradoxically, their perceptions may become a self-fulfilling reality because their (negative) reactions to the change may reinforce its undesirable effects.

That said let’s look at the three paradoxes of organizational change as described in the paper.

Paradoxes of performing

A change initiative is invariably accompanied by restructuring that results in wholesale changes in roles and responsibilities across the organisation. Moreover, since large-scale changes take a long time to implement, there is a longish transition period in which employees are required to perform tasks and activities associated with their old and new roles. During this period, employees may have to deal with competing, even conflicting demands. This, quite naturally, causes stress and anxiety.

Paradoxes of performing relate to contradictions in employees’ self understanding of their identities and roles within the organisation. As such, these paradoxes are characterized by mixed messages from management. As the authors state, people faced with such paradoxes often express feelings of rising frustration with/distrust of management, doubt (inability to choose) or nihilism (futility of choice). This paradox isparticularly common when organisations transition from a traditional (functional) management hierarchy to a matrix structure.

Paradoxes of belonging

Another consequence of organizational restructuring is that old hierarchies and workgroups are replaced by new ones. Adjusting to this requires employees to shift allegiances and develop new work relationships. Leaving the safety of a known group can be extremely stressful. Moreover, since the new structures are rarely defined in detail, at least at the start, there is a great deal of ambiguity as to what it really stands for. It is no surprise, therefore, that some employees attempt to maintain the status quo or even leave while others benefit from the change.

At the heart of this paradox is a double bind where a desire to maintain existing relationships competes with the realization that it is necessary to develop new ones. People react to this differently, depending on their values, motivations and (above all) their ability to deal with ambiguity. Inevitably, such situations are characterized by antagonistic attitudes that accentuate differences and/or peoples’ defensive attitudes that provoke defensiveness in others.

Paradoxes of organizing

The fact that organisations consist of people who have diverse backgrounds, motivations and interests suggests that the process of organizing – which, among things, involves drawing distinctions between groups of people based on their skills – is inherently paradoxical. The authors quote a couple of studies that support this contention. One study described how, “friendly banter in meetings and formal documentation [promoted] front-stage harmony, while more intimate conversations and unit meetings [intensified] backstage conflict.” Another spoke of a situation in which, “…change efforts aimed at increasing employee participation [can highlight] conflicting practices of empowerment and control. In particular, the rhetoric of participation may contradict engrained organizational practices such as limited access to information and hierarchical authority for decision making…”

As illustrated by the two examples quoted in the prior paragraph, a manifestation of a paradox of organizing is that the (new) groups created through the process of organizing can accentuate differences that would not otherwise have mattered. These differences can undermine the new structures and hence, the process of organizing itself.

As the authors suggest, paradoxes of organizing are an inevitable side effects of the process of organizing. The best (and perhaps the only) solution lies in learning to live with ambiguity.

Conclusion

In the end, the paradoxes discussed above arise because change evokes feelings of fear, uncertainty and doubt within individuals and groups. When such emotions dominate, it is natural that people will not be entirely open with each other and may do things that undermine the aims of the change, often even unconsciously.

An awareness of the paradoxes of organizing may tempt one to look for solutions. For example, one might think that they might be resolved by “better communication” or “more clarity regarding expectations and roles.” This is exactly what professional “Change Managers” have (supposedly) been doing for years. Yet these paradoxes remain, which suggests that they are natural consequences of change that cannot be “managed away”; those who must undergo the process of change must also suffer the angst and anxiety that comes with it. If this is so, the advice offered by the authors in the final lines of the paper is perhaps apposite. Quoting from Mihalyi Czikszentmihalyi’s book Finding Flow, they state:

Act always as if the future of the universe depended on what you did, while laughing at yourself for thinking that whatever you do makes any difference . . . It is this serious playfulness, this combination of concern and humility, that makes it possible to be both engaged and carefree at the same time.

…and that is perhaps the best advice I have heard in a long time.