Posts Tagged ‘Philosophy’

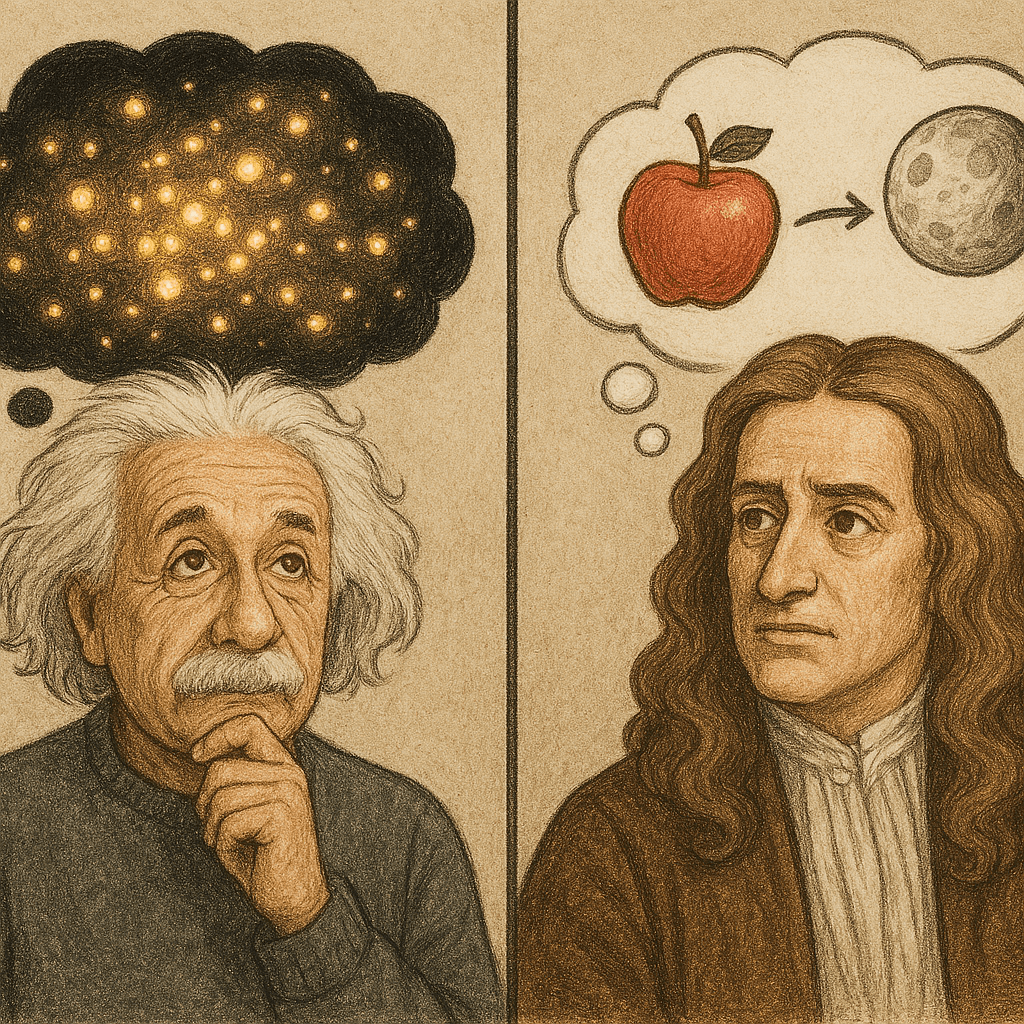

Newton’s apple and Einstein’s photons: on the role of analogy in human cognition

This is the first in a series of reflections on the contrasts between human and machine thinking. My main aim in the present piece is to highlight how humans make sense of novel situations or phenomena for which we have no existing mental models. The basic argument presented here is that we do this by making analogies to what we already know.

Mental models are simplified representations we develop about how the world works. For everyday matters, these representations work quite well. For example, when called upon to make a decision regarding stopping your car on an icy road, your mental model of the interaction between ice and rubber vs road and rubber tells you to avoid sudden braking. Creative work in physics (or any science) is largely about building mental models that offer footholds towards an understanding of the phenomenon being investigated.

So, the question is: how do physicists come up with mental models?

Short answer: By making analogies to things they already know.

–x–

In an article published in 2001, Douglas Hofstadter made the following bold claim:

“One should not think of analogy-making as a special variety of reasoning (as in the dull and uninspiring phrase “analogical reasoning and problem-solving,” a long-standing cliché in the cognitive-science world), for that is to do analogy a terrible disservice. After all, reasoning and problem-solving have (at least I dearly hope!) been at long last recognized as lying far indeed from the core of human thought. If analogy were merely a special variety of something that in itself lies way out on the peripheries, then it would be but an itty-bitty blip in the broad blue sky of cognition. To me, however, analogy is anything but a bitty blip — rather, it’s the very blue that fills the whole sky of cognition — analogy is everything, or very nearly so, in my view.”

The key point he makes is that analogy-making comes naturally to us; we do it several times every day, most often without even being aware of it. For example, this morning when describing a strange odour to someone, I remarked, “It smelt like a mix of burnt toast and horse manure.”

Since analogy enables us to understand the unknown in terms of the known, it should be as useful in creative work as it is in everyday conversation. In the remainder of this article, I will discuss a couple of analogies that led to breakthroughs in physics: one well-known, the other less so.

–x–

Until recently, I had assumed the origin story of the Newton’s theory of gravitation – about a falling apple – to be a myth. I was put right by this very readable history on Newton’s apple tree. Apart from identifying a likely candidate for the tree that bore the fateful fruit, the author presents reminiscences from Newton’s friends and acquaintances about his encounter with the apple. Here’s an account by William Stukely, a close friend of Sir Isaac:

“… After dinner, the weather being warm we went into the garden and drank thea, under the shade of some apple trees, only he and myself. Amidst other discourses, he told me that he was just in the same situation, as when formally the notion of gravity came into his mind. It was occasioned by the fall of an apple, as he sat in a contemplative mood.”

It appears that the creative leap to universal theory of gravitation came from an analogy between a falling apple and a “falling” moon – both being drawn to the centre of the earth. Another account of the Stukely story corroborates this:

“…Amidst other discourse, he told me, he was just in the same situation, as when formerly, the notion of gravitation came into his mind. It was occasioned by the fall of an apple, as he sat in a contemplative mood. Why should that apple always descend perpendicularly to the ground, thought he to him self. Why should it not go sideways or upwards, but constantly to the earth’s centre ? Assuredly, the reason is, that the earth draws it. There must be a drawing power in matter: and the sum of the drawing power in the matter of the earth must be in the earth’s center, not in any side of the earth. Therefore dos this apple fall perpendicularly, or towards the center. If matter thus draws matter, it must be in proportion of its quantity. Therefore the apple draws the earth, as well as the earth draws the apple. That there is a power, like that we here call gravity, which extends its self thro’ the universe…”

Newton’s great of leap intuition was the realisation that what happens at the surface of the earth, insofar as the effect of matter on matter is concerned, is exactly the same as what happens elsewhere in the universe. He realized that both the apple and the moon tend to fall towards the centre of the earth, but the latter doesn’t fall because it has a tangential velocity which exactly counterbalances the force of gravity.

The main point I want to make here is well-summarised in this line from the first article I referenced above: “there can be little doubt that it was through the fall of an apple that Newton commenced his speculations upon the behaviour of gravity.”

–x–

The analogical aspect of the Newton story is easy to follow. However, many analogies associated with momentous advances in physics are not so straightforward because the things physicists deal with are hard to visualise. As Richard Feynman once said when talking about quantum mechanics, “we know we have the theory right, but we haven’t got the pictures [visual mental models] that go with the theory. Is that because we haven’t [found] the right pictures or is it because there aren’t any right pictures?“

He then asks a very important question: supposing there aren’t any right pictures [and the consensus is there aren’t], then is it possible to develop mental models of quantum phenomena?

Yes there is!

However, creating these models requires us to give up the requirement of visualisability: atoms and electrons cannot be pictured as balls or clouds or waves or anything else; they can only be understood through the equations of quantum mechanics. But writing down and solving equations is one thing, understanding their implications is quite another. Many (most?) physicists focus on the former because it’s easier to “shut up and calculate” than develop a feel for what is actually happening.

So, how does one develop an intuition for what is going on when it is not possible to visualise it?

This question brings me to my second analogy. Although it is considerably more complex than Newton’s apple, I hope to give you a sense for the thinking behind it because it is a tour de force of scientific analogy-making.

–x–

The year 1905 has special significance in physics lore. It was the year in which Einstein published four major scientific papers that changed the course of physics.

The third and fourth papers in the series are well known because they relate to the special theory of relativity and mass-energy equivalence. The second builds a theoretical model of Brownian motion – the random jiggling of fine powder scattered on a liquid surface. The first paper of the series provides an intuitive explanation of how light, in certain situations, can be considered to be made up of particles which we now call photons. This paper is not so well-known even though it is the work for which Einstein received the 1921 Nobel Prize for physics. This is the one I’ll focus on as it presents an example of analogy-making par excellence.

To explain the analogy, I’ll first need to set some context around the state of physics at the turn of the last century.

(Aside: Although not essential for what follows, if you have some time I highly recommend you read Feynman’s lecture on the atomic hypothesis, delivered to first year physics students at Caltech in 1962)

–x–

Today, most people do not question the existence of atoms. The situation in the mid1800s was very different. Although there was considerable indirect evidence for the existence of atoms, many influential physicists, such as Ernst Mach, were sceptical. Against this backdrop, James Clerk Maxwell derived formulas relating microscopic quantities such as pressure and temperature of a gas in a container to microscopic variables such as the number of particles and their speed (and energy). In particular, he derived a formula predicting the probability distribution of particle velocities – that is the proportion of particles that have a given velocity. The key assumption Maxwell made in his derivation is that the gas consists of small, inert spherical particles (atoms!) that keep bouncing off each other elastically in random ways – a so-called ideal gas.

The shape of the probability distribution, commonly called the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution, is shown below for a couple of temperatures. As you might expect, the average speed increases with temperature.

I should point out that this was one of the earliest attempts to derive a quantitative link between a macroscopic quantity which we can sense directly and microscopic motions which are inaccessible to our senses. Pause and think about this for a minute. I hope you agree that it is amazing, not the least because it was derived at a time when the atomic hypothesis was not widely accepted as fact.

It turns out that the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution played a key role in Einstein’s argument that light could – in certain circumstances – be modelled as a collection of particles. But to before we get to that, we need to discuss some more physics.

–x–

In the late 19th century it was widely accepted that there are two distinct ways to analyse physical phenomena: as particles (using Newton’s Laws) or as waves (using Maxwell’s Equations for electromagnetic waves, for example).

Particles are localised in space – that is, they are characterised by a position and velocity. Consequently, the energy associated with a particle is localised in space. In contrast, waves are spread out in space and are characterised by a wavelength and frequency as shown in the figure below. Note that the two are inversely related – frequency increases as wavelength decreases and vice versa. The point to note is that, in contrast to particles, the energy associated with a wave is spread out in space.

In the early 1860s, Maxwell established that light is an electromagnetic wave. However visible light represents a very small part of the electromagnetic spectrum which ranges from highly energetic x-rays to low energy radio waves (see the figure below)

The energy of a wave is directly proportional to its frequency – so, high energy X-rays have higher frequencies (and shorter wavelengths) than visible light.

To summarise then, at the turn of the 20th century, the consensus was that light is a wave. This was soon to be challenged from an unexpected direction.

–x–

When an object is heated to a particular temperature, it radiates energy across the entire electromagnetic spectrum. Physically we expect that as the temperature increases, the energy radiated will increase – this is analogous to our earlier discussion of the relationship between the velocity/energy of particles in a gas and the temperature. A practical consequence of this relationship is that blacksmiths can judge the temperature of a workpiece by its colour – red being cooler than white (see chart below).

Keep in mind, though, that visible light is a very small portion of the electromagnetic spectrum: the radiation that a heated workpiece emits extends well beyond the violet and red ends of the visible part of the spectrum.

In the 1880s physicists experimentally established that for a fixed temperature, the distribution of energy emitted by a heated body as a function of frequency is unique. That is – the frequency spread of energy absorbed and emitted by a heated body depends on the temperature alone. The composition of the object does not matter as long as it emits all the energy that it absorbs (a so-called blackbody). The figure below shows the distribution of energy radiated by such an idealised object.

Does the shape of this distribution remind you of something we have seen earlier?

Einstein noticed that the blackbody radiation curve strongly resembles the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution. It is reasonable to assume that others before him would have noticed this too. However, he took the analogy seriously and used it develop a plausibility argument that light could be considered to consist of particles. Although the argument is a little technical, I’ll sketch it out in brief below. Before I do so, I will need to introduce one last physical concept.

–x–

Left to themselves, things tend to move from a state of order to disorder. This applies just as much to atoms as it does to our everyday lives – my workspace tends to move from a state of tidiness to untidiness unless I intervene. In the late 1800s physicists invented a quantitative measure of disorder called entropy. The observation that things tend to become disordered (or messy) if left alone is enshrined in the second law of thermodynamics which states that the entropy of the universe is increasing.

To get a sense for the second law, I urge you to check out this simulation which shows how two gases (red and green) initially separated by a partition tend to mix spontaneously once the partition is removed. The two snapshots below show the initial (unmixed) and equilibrium (mixed) states.

Snapshot 1: Time=0, ordered state, low entropy

Snapshot 2: Time = 452 seconds, disordered (mixed) state, high entropy

The simulation gives an intuitive feel for why a disordered system will never go back to an ordered state spontaneously. It is the same reason that sugar, once mixed into your coffee will never spontaneously turn into sugar crystals again.

Why does the universe behave this way?

The short answer is that there are overwhelmingly more disordered states in the universe than ordered ones. Hence, if left to themselves, things will end up being more disordered (or messy) than they were initially. This is as true of my desk as it is of the mixing of two gases.

Incidentally, the logic of entropy applies to our lives in other ways too. For example, it explains why we have far fewer successes than failures in our lives. This is because success typically requires many independent events to line up in favourable ways, and such a confluence is highly unlikely. See my article on the improbability of success for a deeper discussion of this point.

I could go on about entropy as it is fertile topic, but I ‘ll leave that for another time as I need to get back to my story about Einstein’s photons and finish up this piece.

–x–

Inspired by the similarity between the energy distribution curves of blackbody radiation and an ideal gas, Einstein made the bold assumption that the light bouncing around inside a heated body consisted of an ideal gas of photons. As he noted in his paper, “According to the assumption to be contemplated here, when a light ray is spreading from a point, the energy is not distributed continuously over ever-increasing spaces, but consists of a finite number of energy quanta that are localized in points in space, move without dividing, and can be absorbed or generated only as a whole.“

In essence he assumed that the energy associated with electromagnetic radiation is absorbed or emitted in discrete packets akin to particles. This assumption enabled him to make an analogy between electromagnetic radiation and an ideal gas. Where did the analogy itself come from. The physicist John Rigden notes the following in this article, “what follows comes from Einstein’s deep well of intuition; specifically, his quantum postulate emerges from an analogy between radiation and an ideal gas.” In other words, we have no idea!

Anyway, with the analogy assumed, Einstein compared the change in entropy when an ideal gas consisting of particles is compressed from a volume

to volume

at a constant temperature

(or energy

) to the change in entropy when a “gas of electromagnetic radiation” of average frequency

undergoes a similar compression.

Entropy is typically denoted by the letter , and a change in any physical quantity is conventionally denoted by the Greek letter

, so the change in entropy is denoted by

. The formulas for the two changes in entropy mentioned in the previous paragraph are:

The first of the two formulas was calculated from physics that was well-known at the time (the same physics that led to the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution). The second was based on the analogy that Einstein made between an ideal gas and electromagnetic radiation.

Comparing the exponents in the two formulas, we get:

Which basically tells us that the light contained in the heated container consists of discrete particles that have an energy proportional to the frequency

. The formula relates a wave characteristic (frequency) to the energy of a photon. In Einstein’s original derivation, the quantity denoted by

had a more complicated expression, but he recognised that it was identical to a universal constant identified by Max Planck some years earlier. It is important to note that the connection to Planck’s prior work provided weak evidence for the validity of Einstein’s analogy, but not a rigorous proof.

–x–

As Rigden notes, “Einstein’s “revolutionary” paper has the strange word “heuristic” in the title. This word means that the “point of view” developed – that is, the light particle – is not in itself justified except as it guides thinking in productive ways. Therefore, at the end of his paper, Einstein demonstrated the efficacy of light quanta by applying them to three different phenomena. One of these was the photoelectric effect [which to this day remains] the phenomenon that demonstrated the efficacy of Einstein’s light quantum most compellingly.” (Note: I have not described the other two phenomena here – read Rigden’s article for more about them)

Einstein’s could not justify his analogy theoretically, which is why he resorted to justification by example. Even so many prominent physicists remained sceptical. As Rigden notes, “Einstein’s big idea was universally rejected by contemporary physicists; in fact, Einstein’s light quantum was derisively rejected. When Max Planck, in 1913, nominated Einstein for membership of the Prussian Academy of Science in Berlin, he apologized for Einstein by saying, “That sometimes, as for instance in his hypothesis on light quanta, he may have gone overboard in his speculations should not be held against him.” Moreover, Robert Millikan, whose 1916 experimental data points almost literally fell on top of the straight line predicted for the photoelectric effect by Einstein’s quantum paper, could not accept a corpuscular view of light. He characterized Einstein’s paper as a “bold, not to say reckless, hypothesis of an electro-magnetic light corpuscle of energy hν, which…flies in the face of thoroughly established facts of interference…In his 1922 Nobel address, Niels Bohr rejected Einstein’s light particle. “The hypothesis of light-quanta”, he said, “is not able to throw light on the nature of radiation.” It was not until Arthur Compton’s 1923 X-ray scattering experiment, which showed light bouncing off electrons like colliding billiard balls, that physicists finally accepted Einstein’s idea.”

It took almost twenty years for the implications of Einstein’s bold analogy to be accepted by physicists!

–x–

Perhaps you’re wondering why I’ve taken the time to go through these two analogies in some detail. My reason is simple: I wanted to illustrate the kind of lateral and innovative thinking that humans are uniquely capable of.

I will refrain from making any remarks about whether LLM-based AIs are capable of such thinking. My suspicion – and I’m in good company here – is that the kind of thinking which leads to new insights involves a cognitive realm that has little do with formal reasoning. To put it plainly, although we may describe our ideas using language, the ideas themselves – at least the ones that are truly novel – come from another kind of logic. In the next article in this series, I will speculate on what that logic might be. Then, in a following piece, I will discuss its implications for using AI in ways that augment our capabilities rather than diminish them.

–x—x–

Acknowledgements: the above discussion of Einstein’s analogy are based on this lecture by Douglas Hofstadter and this article by John Rigden. I’d also like to acknowledge Michael Fowler from the University of Virginia for his diffusion simulation (https://galileoandeinstein.phys.virginia.edu/more_stuff/Applets/Diffusion/diffusion.html) which I have used for the entropy explanation in the article.

More than just talk: rational dialogue in project environments

Prologue

The meeting had been going on for a while but it was going nowhere. Finally John came out and said it, “There is no way I can do this in 2 days,” he said. “It will take me at least a week.”

There it was, the point of contention between the developer and his manager. Now that it was out in the open, the real work of meeting could begin; the two could start talking about a realistic delivery date.

The manager, let’s call him Jack, was not pleased, “Don’t tell me a simple two-page web app – which you have done several times before I should add – will take you a week to do. ”

“OK, let me walk you through the details,” said John.

….and so it went for another half hour or so, Jack and John arguing about what would be a reasonable timeframe for completing the requested work.

Dialogue, rationality and action

Most developers, designers and indeed most “doers” on project teams– would have had several conversations similar to the one above. These folks spend a fair bit of time discussing matters relating to the projects they work on. In such discussions, the aim is to come to a shared understanding of the issue under discussion and a shared commitment on future action. In the remainder of this post I’ll take a look at project discussions from a somewhat philosophical perspective, with a view to understanding some of the obstacles to open dialogue and how they can be addressed.

When we participate in discussions we want our views to be taken seriously. Consequently, we present our views through statements that we hope others will see as being rational – i.e. based on sound premises and logical thought. One presumes that John – when he made his claim about the delivery date being unrealistic – was willing to present arguments that would convince Jack that this was indeed so. The point is that John is judged (by Jack and others in the meeting) based on the validity of the statements he (John) makes. When Jack’s validity claims are contested, debate ensues with the aim of getting to some kind of agreement.

The philosophy underlying such a process of discourse (which is simply another word for “debate” or “dialogue”) is described in the theory of communicative rationality proposed by the German philosopher Jurgen Habermas. The basic premise of communicative rationality is that rationality (or reason) is tied to social interactions and dialogue. In other words, the exercise of reason can occur only through dialogue. Such communication, or mutual deliberation, ought to result in a general agreement about the issues under discussion. Only once such agreement is achieved can there be a consensus on actions that need to be taken. Habermas refers to the latter as communicative action, i.e. action resulting from collective deliberation.

[Note: Just to be clear: I have not read Habermas’ books, so my discussion is based entirely on secondary sources: papers by authors who have studied Habermas in detail. Incidentally, the Wikipedia article on the topic is quite good, and well worth a read.]

Validity Claims

Since the objective in project discussions is to achieve shared understanding of issues and shared commitment on future action, one could say that such discussions are aimed at achieving communicative action. The medium through which mutual understanding is achieved is speech – i.e. through statements that a speaker makes based on his or her perceptions of reality. Others involved in the dialogue do the same, conveying their perceptions (which may or may not match the speaker’s).

Now, statements made in discussions have implicit or explicit validity claims – i.e. they express a speaker’s belief that something is true or valid, at least in the context of the dialogue. Participants who disagree with a speaker are essentially contesting claims. According to the theory of communicative action, every utterance makes the following validity claims:

- It makes a claim about objective (or external) reality. John’s statement about the deadline being impossible refers to the timing of an objective event – the delivery of working software. Habermas refers to this as the truth claim.

- It says something about social reality – that is, it expresses something about the relationship between the speaker and listener(s). The relationship is typically defined by social or workplace norms, for example – the relationship between a manager and employee as in the case of John and Jack. John’s statement is an expression of disagreement with his manager. Of course, he believes his position is justified – that it ought to take about a week to deliver the software. Habermas refers to this as the rightness claim.

- It expresses something about subjective reality – that is, the speaker’s personal viewpoint. John believes, based on his experience, intutition etc., that the deadline is impossible. For communication to happen, Jack must work on the assumption that John is being honest – i.e. that John truly believes the deadline is impossible, even though Jack may not agree. Habermas refers to this as the truthfulness claim.

The validity claims and their relation to rationality are nicely summed up in the Wikipedia article on communicative rationality, and I quote:

By earnestly offering a speech act to another in communication, a speaker claims not only that what they say is true but also that it is normatively right and honest . Moreover, the speaker implicitly offers to justify these claims if challenged and justify them with reasons. Thus, if a speaker, when challenged, can offer no acceptable reasons for the normative framework they implied through the offering of a given speech act, that speech act would be unacceptable because it is irrational.

When John says that the task is going to take him a week, he implies that he can justify the statement (if required) in three ways: it will take him a week (objective), that it ought to take him a week (normative – based on rightness) and that he truly believes it will take him a week (subjective).

In all dialogues validity claims are implied, but rarely tested; we usually take what people say at face value, we don’t ask them to justify their claims. Nevertheless, it is assumed that they can offer justifications should we ask them to. Naturally, we will do so only when we have reason to doubt the validity of what they say. It is at that point that discourse begins. As Wener Ulrich puts it in this paper:

In everyday communication, the validity basis of speech is often treated as unproblematic. The purpose consists in exchanging information rather than in examining validity claims. None of the three validity claims is then made an explicit subject of discussion. It is sufficient for the partners to assume (or anticipate, as Habermas likes to say) that speakers are prepared to substantiate their claims if asked to do so, and that it is at all times possible for the participants to switch to a different mode of communication in which one or several validity claims are actually tested. Only when validity claims do indeed become problematic, as one of the participants feels compelled to dispute either the speaker’s sincerity or the empirical and/or normative content of his statements, ordinary communication breaks down and discourse begins.

Progress in project discussions actually depends on such breakdown in “ordinary communication” – good project decisions emerge from open deliberation about the pros and cons of competing approaches. Only once this is done can one move to action.

Conditions for ideal discourse

All this sounds somewhat idealistic, and it is. Habermas noted five prerequisites for open debate. They are:

- Inclusion: all affected parties should be included in the dialogue.

- Autonomy: all participants should be able to present and criticise validity claims independently.

- Empathy: participants must be willing to listen to and understand claims made by others.

- Power neutrality: power differences (levels of authority) between participants should not affect the discussion.

- Transparency: participants must not indulge in strategic actions (i.e. lying!).

In this paper Bent Flyvbjerg adds a sixth point: that the group should be able to take as long as it needs to achieve consensus – Flyvbjerg calls this the requirement of unlimited time.

From this list it is clear that open discourse (or communicative rationality) is an ideal that is difficult to achieve in practice. Nevertheless, because it is always possible to improve the quality of dialogue on projects, it behooves us as project professionals to strive towards the ideal. In the next section I’ll look at one practical way to do this.

Boundary judgements

Most times in discussions we jump straight to the point, without bothering to explain the assumptions that underpin our statements. By glossing over assumptions, however, we leave ourselves open to being misunderstood because others have no means to assess the validity of our statements. Consequently it becomes difficult for them to empathise with us. For example, when John says that it is impossible to finish the work in less than a week, he ought to support his claim by stating the assumptions he makes and how these bear on his argument. He may be assuming that he has to do the work in addition to all the other stuff he has on his plate. On the other hand, he may be assuming too much because his manager may be willing to reassign the other stuff to someone else. Unless this assumption is brought out in the open, the two will continue to argue without reaching agreement.

Werner Ulrich pointed out that the issue of tacit assumptions and unstated frameworks is essentially one of defining the boundaries within which one’s claims hold. He coined the term boundary judgement to describe facts and norms that a speaker deems relevant to his or her statements. A boundary judgement determines the context within which a statement holds and also determines the range of validity of the statement. For example, John is talking about the deadline being impossible in the context of his current work situation; if the situation changed, so might his estimate. Ulrich invented the notion of boundary critique to address this point. In essence, boundary critique is a way to uncover boundary judgements by asking the right questions. According to Ulrich, such boundary questions probe the assumptions made by various stakeholders. He classifies boundary questions into four categories. These are:

- Motivation: this includes questions such as:

- Why are we doing this project?

- Who are we doing it for?

- How will we measure the benefits of the project once it is done?

- Power: this includes questions such as:

- Who is the key decision-maker regarding scope?

- What resources are controlled by the decision-maker?

- What are the resources that cannot be controlled by the decision-maker (i.e. what are the relevant environmental factors)?

- Knowledge: This includes:

- What knowledge is needed to do this work?

- Who (i.e which professionals) have this knowledge?

- What are the key success factors – e.g. stakeholder consensus, management support, technical soundness etc?

- Legitimation: This includes:

- Who are the stakeholders (including those that are indirectly affected by the project)?

- How do we ensure that the interests of all stakeholders are taken into account?

- How can conflicting views of project objectives be reconciled?

The questions above are drawn from a paper by Ulrich. I have paraphrased them in a way that makes sense in project environments.

Many of these questions are difficult to address openly, especially those relating to power and legitimation. Answers to these often bump up against organisational politics or power. The point, however, is that once these questions are asked, such constraints become evident to all. Only after this happens can discourse proceed in the full knowledge of what is possible and what isn’t.

Before closing this section I’ll note that there are other techniques that do essentially the same thing1, but I won’t discuss them here as I’ve already exceeded a reasonable word count.

Conclusion

Someone recently mentioned to me that the problem in project meetings (and indeed any conversation) is that participants see their own positions as being rational, even when they are not. Consequently, they stick to their views, even when faced with evidence to the contrary. According to the theory of communicative rationality, however, such folks aren’t being rational because they do not subject their positions and views to “trial by argumentation”. Rationality lies in dialogue, not in individual statements or positions. A productive discussion is one in which validity claims are continually challenged until they converge on an optimal decision. The best (or most rational) position is one that emerges from such collective deliberation.

In closing, a caveat is in order – a complete discussion of dialogue in projects (or organisations) would take an entire book and more. My discussion here has merely highlighted a few issues (and a technique) that I daresay are rarely touched upon in management texts or courses. There are many more tools and techniques that can help improve the quality of discourse within organisations. Paul Culmsee and I discuss some of these in our book, The Heretic’s Guide to Best Practices.

1 Those familiar with soft systems methodology (SSM) will recognise the parallels between Ulrich’s approach and the CATWOE checklist of SSM. CATWOE is essentially a means of exposing boundary judgements.