More than stochastic parrots: understanding and reasoning in LLMs

The public release of the ChatGPT last year has spawned a flood of articles and books on how best to “leverage” the new technology. Majority of these provide little or no explanation of how Large Language Models (LLMs), such as ChatGPT, do what they do.

In this article, I discuss some of the surprising things that LLMs can do, with the intent of developing a rudimentary sense for how they “understand” meaning. I begin with Alan Turing’s classic paper, which will lead us on to a few demos of ChatGPT capabilities that might be considered unusual because they combine two or more very different skills. Following that I will touch upon some recent research on how LLMs are able to develop an understanding of meaning.

A caveat before we proceed: the question of how LLMs develop representations of concepts and meaning is still not well understood, therefore much of what I say in the latter part of this piece is tentative. Nevertheless, I offer it here for two reasons. Firstly, to show that it is not hard to understand the essence, if not the detail, of what is going on at the frontier of this exciting field. Secondly, that the mental models that come from such an understanding can help you use these tools in interesting and creative ways.

–x–

In his classic paper, Turing posed the question: can machines think?

Noting that the question, as posed, invites endless arguments about what constitutes a “machine” or what it means to “think,” he reframed it in terms of what he called an imitation game:

“[the game] is played with three people, a man (A), a woman (B), and an interrogator (C) who may be of either sex. The interrogator stays in a room apart [in] front [of] the other two [and cannot see either]. The object of the game for the interrogator is to determine which of the other two is the man and which is the woman. He knows them by labels X and Y, and at the end of the game he says either “X is A and Y is B” or “X is B and Y is A.” The interrogator is allowed to put questions to A and B thus:

C: Will X please tell me the length of his or her hair?

Now suppose X is actually A, then A must answer. It is A’s object in the game to try and cause C to make the wrong identification. His answer might therefore be:

“My hair is shingled, and the longest strands are about nine inches long.”

In order that tones of voice may not help the interrogator the answers should be written,or better still, typewritten.

…The object of the game for the third player (B) is to help the interrogator. The best strategy for her is probably to give truthful answers. She can add such things as “I am the woman, don’t listen to him!” to her answers, but it will avail nothing as the man can make similar remarks.

We now ask the question, “What will happen when a machine takes the part of A in this game?” Will the interrogator decide wrongly as often when the game is played like this as he does when the game is played between a man and a woman? These questions replace our original, “Can machines think?”

This is the basis of the well-known Turing Test.

In the paper, which is well worth a read, Turing proposes some specimen questions that one might ask the machine, along with responses from a hypothetical thinking machine:

Q: Please write me a sonnet on the subject of the Forth Bridge.

A: Count me out on this one. I never could write poetry.

Q: Add 34957 to 70764.

A: (Pause about 30 seconds and then give as answer) 105621.

….

Declining a difficult language task and making an error in simple arithmetic (was that intentional??) are very human reactions. Nevertheless, I think readers would agree with Turing about the suitability of the Q&A format as a probe of knowledge and reasoning capabilities of machines.

–x–

I thought it would be interesting to pose Turing’s questions to ChatGPT (v3.5). Here is how it responded to the first question:

User

Please write me a sonnet on the subject of the Forth bridge.

ChatGPT

Amidst the rolling waves, a structure bold,

The Forth Bridge emerges, a sight to hold.

Its iron arms outstretched, a feat of might,

Connecting lands, spanning the waters’ fight.

A symphony of steel, a dance of grace,

A testament to human skill and space.

High above the tides, it proudly stands,

A link between two shores, crafted by hands.

Against the winds that howl with fierce delight,

It stands unwavering through day and night.

Its crimson hue against the Scottish sky,

A beacon of connection soaring high.

Oh, Forth Bridge, a marvel of design,

A timeless bond ‘twixt land and sea’s confines.

That is surprisingly good! Unnaturally so, because it spat out a response in a few seconds, a far shorter timeframe than one in which human could produce a sonnet on demand.

I also learnt something that I did not know – that the bridge is red in colour. That gave me an angle to query ChatGPT further:

User

In the eleventh line of your sonnet which reads “Its crimson hue against the Scottish sky,” would not “a scarlet hue” do as well or better?

ChatGPT

Certainly, “a scarlet hue” would indeed work well in that line. Here’s the revised version of the sonnet:

…and it printed out the entire sonnet again with “crimson” replaced with “scarlet.” It is interesting that ChatGPT did not argue the point about the suitability of the hue. It appears to have been trained to be agreeable, something that others have commented on.

I pushed the point further, asking for its opinion on scarlet vs crimson:

User

Do you think that works better than the original version?

ChatGPT

Both versions have their own merits, and the choice between “crimson hue” and “scarlet hue” is largely a matter of personal preference and the imagery you want to convey. “Scarlet hue” does indeed evoke a vivid and intense image, emphasizing the boldness of the bridge’s color against the sky. On the other hand, “crimson hue” also paints a vibrant and rich picture, aligning with traditional descriptions of the bridge’s color. Ultimately, both options are valid, and the decision depends on the tone and imagery you want to convey in your sonnet.

That’s pretty good: it gave me a reason for its choice, but also left me feeling that my suggestion is not entirely stupid. Very agreeable indeed!

From the above, one might say that ChatGPT3.5 aces Turing’s question. Ironically, what gives it away as a non-human is a) its speed, b) its extreme agreeability and b) the comprehensiveness of its responses. No human would respond so quickly, politely, and comprehensively to such a difficult query.

Note that ChatGPT4 does much better than the 3.x version on most tasks, so you may want to try the above if you have access to the 4.x version.

–x–

At this point you may be asking: what is ChatGPT doing…and why does it work? This question is partially answered in a highly readable article by Stephen Wolfram (also available as a book). I’ll leave you to read that article later, but I’d like to pick up on a point he makes in it: LLMs excel in linguistic tasks (like composing poetry) but are less proficient in dealing with questions that involve complex reasoning (such as logic puzzles or mathematical reasoning). That is true, but it should be noted that proficiency in the former also implies some facility with the latter, and I’ll make this point via a couple of examples towards the end of this piece.

LLMs’ proficiency in language makes sense: these models are trained on a huge quantity of diverse texts – ranging from fiction to poetry to entire encyclopedias – so they know about different styles of writing and can draw upon a significant portion of human knowledge when synthesizing responses.

However, can one claim that they have “learnt” the meaning of what they “talk” about?

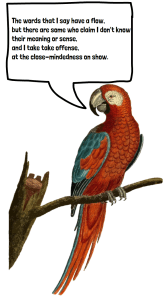

In an award-winning paper published in 2020, Emily Bender and Timothy Koller argued that “system[s] trained only on form [have] a priori no way to learn meaning” – in other words, models that are trained on vast quantities of text cannot have any “understanding” of meaning. In the conclusion they note that, “…large language models such as BERT do not learn “meaning”; they learn some reflection of meaning into the linguistic form which is very useful in applications.”

In a follow up paper, in which the now-famous term stochastic parrot was coined, Bender and her colleagues made the important point that, “Text generated by an LLM is not grounded in communicative intent, any model of the world, or any model of the reader’s state of mind. It can’t have been, because the training data never included sharing thoughts with a listener, nor does the machine have the ability to do that.” This is an important point to keep in mind as one converses with ChatGPT – that it cannot read intent as a human might be able to, all it can go by is the prompt it is given.

A few lines later, they note that, “Contrary to how it may seem when we observe its output, a [Language Model] is a system for haphazardly stitching together sequences of linguistic forms it has observed in its vast training data, according to probabilistic information about how they combine, but without any reference to meaning: a stochastic parrot.”

However, the responses that I got from ChatGPT seemed more coherent that “haphazardly stitched together” sequences of forms it has observed in the past. It seems like it is working off some kind of conceptual model.

Which begs the question: how does it do that?

–x–

To shed some light on this question, I will now discuss two papers presented at a recent (August 2023) meeting on LLMs held at UC Berkeley.

In a talk presented at the meeting, Steven Piantadosi argued that LLMs “understand” the meaning of words the same way that humans associate meanings with them: through the different concepts that words are used to express. This is called conceptual role semantics, and is based on the following two claims:

- The meanings of linguistic expressions are determined by the contents of the concepts and thoughts they can be used to express.

- The contents of concepts and thoughts are determined by their functional role in a person’s psychology.

Piantadosi’s argument (as I understand it) is that LLMs develop internal representations of the varied meanings of words and phrases in a manner analogous to humans – i.e., through repeated exposure to words / phrases used to express (and reason about) different concepts. To be sure, the representations in silico are very different from those in our wetware. However, the claim that the models might learn such representations in an emergent manner, as they are exposed to more and more text, is not unreasonable.

Those interested in exploring this idea further may want to check out Piantadosi’s paper.

At the same meeting, Sanjeev Arora gave a talk on a theory of skill emergence in LLMs. I did not follow the details of his arguments, so I won’t comment on them here. However, the point he made is that LLMs learn to combine multiple skills in ways that they are unlikely to have been exposed to in training – and that they are able to do so because the vast corpus they have been trained on contains many examples of multiple mixed skills (such as parsing questions, essay writing, reasoning etc). Through continued exposure to several diverse examples, it “learns” how to combine such skills inductively. If this does not sound plausible, recall that transfer learning is essentially a demonstration of the kind of inductive reasoning that Arora refers to.

A surprising prediction of Arora’s theory is that proficiency in different combinations of multiple skills arises in the same manner that proficiencies in single skills are developed. As he notes in the conclusion of the paper on which his talk was based:

“We have proposed a theoretical framework for understanding emergence of skills when language models are scaled up. A key insight is that reduction in excess cross entropy loss drives skill acquisition, together with the assumption that normal language —down to short paragraph level— already utilizes multiple skills, mixed up randomly. Need for mechanistic insight is sidestepped using Scaling Law, which quantifies a powerful inductive bias in pre-trained models…a concrete example of this inductive bias is that in our framework proficiency in combinations of skills arises just as naturally as proficiency in the individual skills themselves, and need not require seeing examples of all (or even most) of these combinations in the training set. This has relevance to the ongoing debate about the extent of “understanding” that current models have, and their ability to address novel settings.”

The emergence of proficiency in multiple skills is interesting, and sort of “explains” ChatGPT’s surprisingly good Forth Bridge Sonnet. So, I thought it would be interesting to end this piece with a test that combines yet another set of skills, which I hope you will find even more surprising: composing verse and mathematical reasoning.

–x–

User

Can you give me a proof that the square root of two is irrational in sonnet form?

ChatGPT

Amidst the realm of numbers, set and firm,

Lies sqrt(2), a mystery to discern.

Suppose, with hope, a fraction could express,

Its form a/b, where a and b impress.

In seeking simplest terms, we strive to find,

GCD, their common divisor kind.

Yet let us dream that a and b stand free,

No common factors bind, with certainty.

Now, let’s assume it’s true, and so proceed,

With algebraic steps, our wits to feed.

Squared a/b, and two, a match we chase,

Equation thus: a^2 = 2 * b^2 in space.

Now a must be even, so we glean,

For if odd, a^2, odd too, is seen.

Then b must follow suit, an even mate,

Else b^2 odd, a contradiction’s gate.

But wait, contradiction further unfurls,

2 * b^2 even, as math whirls.

Thus a^2 even, a even, we derive,

Contradicting a’s oddness, math does strive.

This contradiction shows our first intent,

A fraction’s claim, by logic, is rent.

The square root of two, irrational true,

Its proof in sonnet form, now stands to view.

Which is a reasonably accurate, though admittedly confusing, description of Euclid’s proof of the irrationality of the square root of 2 in (not so good!) verse.

–x–

Finally, to close the loop, I asked ChatGPT a couple of math problems, starting with Turing’s elementary arithmetic question:

User

Add 34957 to 70764.

ChatGPT

The sum of 34957 and 70764 is 105721.

Unsurprisingly, it gets that right.

What about more complex mathematical reasoning? I pulled out a word problem from a Year 6 maths book:

User

Zach buys two hot dogs and three drinks for $14. Drinks cost $2 each. How much does one hot dog cost?

ChatGPT

Let’s denote the cost of one hot dog as “H” dollars.

Given that Zach buys two hot dogs and three drinks for $14, we can set up the equation:2H + 3(2) = 14Simplify the equation:

2H + 6 = 14

Subtract 6 from both sides:

2H = 8

Now, divide both sides by 2:

H = 4

Therefore, one hot dog costs $4.

That blew me away. Not only did it get the answer right, it presented the reasoning behind it.

Understanding reasoning capabilities of LLMs is a new but very active area of research and I’ll just point readers to two recent papers in this area:

In this paper, Nikunj Saunshi and Vivek Gaur explore the capabilities of LLM to do symbolic reasoning – i.e., to convert math word problems to equations and solve them, much as in the example above.

In this mammoth paper (which I’m yet to go through in detail), Sebastien Bubeck and his colleagues investigate GPT-4’s ability to solve novel and difficult tasks that span mathematics, coding, vision, medicine, law, psychology and more, without needing any special prompting.

I should mention that we have little knowledge at present as to how LLMs reason. However, in view of the examples above (and many more in the referenced papers), it seems reasonable to conclude that state-of-the-art LLMs are more than stochastic parrots.

–x–

In this article I have touched upon the question of how these models “understand meaning,” starting from Turing’s original imitation game to a couple of examples drawn from current research. I think he would have been impressed by the capabilities of current LLMs…and keep in mind that state-of-the-art models are even better than the ones I have used in my demos.

It seems appropriate to close this piece with some words on the implications of machines that “understand meaning.” The rapid improvements in LLM capabilities to comprehend is disconcerting, and provokes existential questions such as: how much better (than us) might these tools become? what implications does that have for us? Or, closer home: what does it mean for me and my job? All these are excellent questions that have no good answers at the moment. The only thing that is clear is the genie is out in the wild and our world has forever changed. How can we thrive in the new world where machines understand meaning better than we do? I hope to explore this question in future articles by sketching out some thoughts on how these tools can be used in ways that enhance rather than diminish our own capabilities.

[…] reason symbolically, tell stories, plan, pretend…and even (appear to) empathise. Indeed, so fascinating and surprising are their properties that they evoke comparisons with legends and myths of […]

LikeLike

Of golems and LLMs | Eight to Late

November 15, 2023 at 6:06 am

[…] enables them to do some pretty mind-blowing things that look like reasoning. See my post, More Than Stochastic Parrots, for some examples of this and keep in mind they are from a much older version of […]

LikeLike

Seeing through AI hype – some thoughts from a journeyman | Eight to Late

May 29, 2024 at 5:14 am

[…] the ability to combine different skills or to solve puzzles / math problems using reasoning (see this post for examples of these). Before dealing with the latter, I provide a brief introduction to […]

LikeLike

Towards a public understanding of AI – notes from an introductory class for a general audience | Eight to Late

November 19, 2024 at 4:00 am