Archive for the ‘Decision Making’ Category

From ambiguity to action – a paper preview

The powerful documentary The Social Dilemma highlights the polarizing effect of social media, and how it hinders our collective ability to address problems that impact communities, societies and even nations. Towards the end of the documentary, the technology ethicist, Tristan Harris, makes the following statement:

“If we don’t agree on what is true or that there’s such a thing as truth, we’re toast. This is the problem beneath all other problems because if we can’t agree on what is true, then we can’t navigate out of any of our problems.”

The central point the documentary makes is that the strategies social media platforms use to enhance engagement also tend to encourage the polarization of perspectives. A consequence is that people on two sides of a contentious issue become less likely to find common ground and build a shared understanding of a complex problem.

A similar dynamic plays out in organisations, albeit on a smaller and less consequential scale. For example, two departments – say, sales and marketing – may have completely different perspectives on why sales are falling. Since their perspectives are different, the mitigating actions they advocate may be completely different, even contradictory. In a classic paper, published half a century ago, Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber coined the term wicked problem to describe such ambiguous dilemmas.

In contrast, problems such as choosing the cheapest product from a range of options are unambiguous because the decision criteria are clear. Such problems are sometimes referred to as tame problems. As an aside, it should be noted that organisations often tend to treat wicked problems as tame, with less-than-optimal consequences down the line. For example, choosing the cheapest product might lead to larger long-term costs due to increased maintenance, repair and replacement costs.

The problem with wicked problems is that they cannot be solved using rational approaches to decision making. The reason is that rational approaches assume that a) the decision options can be unambiguously determined upfront, and b) that they can be objectively rated. This implicitly assumes that all those who are impacted by the decision will agree on the options and the rating criteria. Anyone who has been involved in making a contentious decision will know that these are poor assumptions. Consider, for example, management and employee perspectives on an organizational restructuring.

In a book published in 2016, Paul Culmsee and I argued that the difference between tame and wicked problems lies in the nature of uncertainty associated with the two. In brief, tame problems are characterized by uncertainties that can be easily quantified (e.g., cost or time in projects) whereas wicked problems are characterized by uncertainties that are hard to quantify (e.g., the uncertainties associated with a business strategy). One can think of these as lying at the opposite ends of an ambiguity spectrum, as shown below:

It is important to note that most real-world problems have both quantifiable and unquantifiable uncertainties and the first thing that one needs to do when one is confronted with a decision making situation is to figure out, qualitatively, where the problem lies on the ambiguity spectrum:

The key insight is that problems that have quantifiable uncertainties can be tackled using rational decision making techniques whereas those with unquantifiable uncertainties cannot. Problems of the latter kind are wicked, and require a different approach – one that focuses on framing the problem collectively (i.e., involving all impacted stakeholders) prior to using rational decision making approaches to address it. This is the domain of sensemaking, which I like to think of as the art of extracting or framing a problem from a messy situation.

Sensemaking is something we all do instinctively when we encounter the unfamiliar – we try to make sense of the situation by framing it in familiar terms. However, in an unfamiliar situation, it is unlikely that a single perspective on a problem will be an appropriate one. What is needed in such situations is for people with different perspectives to debate their views openly and build a shared understanding of the problem that synthesizes the diverse viewpoints. This is sometimes called collective sensemaking.

Collective sensemaking is challenging because it involves exactly the kind of cooperation that Tristan Harris calls for in the quote at the start of this piece.

But when people hold conflicting views on a contentious topic, how can they ever hope to build common ground? It turns out there are ways to build common ground, and although they aren’t perfect (and require diplomacy and doggedness) they do work, at least in many situations if not always. A technique I use is dialogue mapping which I have described in several articles and a book co-written with Paul Culmsee.

Regardless of the technique used, the point I’m making is that when dealing with ambiguous problems one needs to use collective sensemaking to frame the problem before using rational decision making methods to solve it. When dealing with an ambiguous problem, the viability of a decision hinges on the ability of the decision maker to: a) help stakeholders distinguish facts from opinions, b) take necessary sensemaking actions to find common ground between holders of conflicting opinions, and c) build a base of shared understanding from which a commonly agreed set of “facts” emerge. These “facts” will not be absolute truths but contingent ones. This is often true even of so-called facts used in rational decision making: a cost quotation does not point to a true cost, rather it is an estimate that depends critically on the assumptions made in its calculation. Such decisions, therefore, cannot be framed based on facts alone but ought to be co-constructed with those affected by the decision. This approach is the basis of a course on decision making under uncertainty that I designed and have been teaching across two faculties at the University of Technology Sydney for the last five years.

In a paper, soon to be published in Management Decision, a leading journal on decision making in organisations, Natalia Nikolova and I describe the principles and pedagogy behind the course in detail. We also highlight the complementary nature of collective sensemaking and rational decision making, showing how the former helps in extracting (or framing) a problem from a situation while the latter solves the framed problem. We also make the point that decision makers in organisations tend to jump into “solutioning” without spending adequate time framing the problem appropriately.

Finally, it is worth pointing out that the hard sciences have long recognized complementarity to be an important feature of physical theories such as quantum mechanics. Indeed, the physicist Niels Bohr was so taken by this notion that he inscribed the following on his coat of arms: contraria sunt complementa (opposites are complementary). The integration of apparently incompatible elements into a single theory or model can lead to a more complete view of the world and hence, how to act in it. Summarizing the utility of our approach in a phrase: it can help decision makers learn how to move from ambiguity to action.

For copyright reasons, I cannot post the paper publicly. However, I’d be happy to share it with anyone interested in reading / commenting on it – just let me know via a comment below.

Note added on 13 May 2022:

The permalink to the published online version is: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/MD-06-2021-0804/full/html

Monte Carlo Simulation of Projects – an (even simpler) explainer

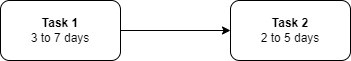

In this article I’ll explain how Monte Carlo simulation works using an example of a project that consists of two tasks that must be carried out sequentially as shown in the figure:

Task 1 takes 3 to 7 days

Task 2 takes 2 to 5 days

The two tasks do not have any dependencies other than that they need to be completed in sequence.

(Note: in case you’re wondering about “even simpler” bit in the title – the current piece is, I think, even easier to follow than this one I wrote up some years ago).

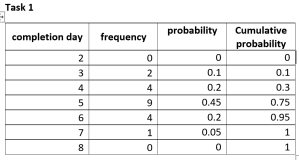

Assume the project has been carried a number of times in the past – say 20 times – and we have the data shown below for the two tasks. For each task, we have the frequency of completion by day. So, Task 1 was completed twice on day 3 , four times on day 4 and so on. Similarly, Task 2 was completed twice on the 2nd day after the task started and 10 times the 3rd day after the task started and so on.

Consider Task 1. Since it was completed 2 times on day 3 and 4 times on day 4, it is reasonable to assume that it twice as likely that it will finish on day 4 than on day 3. In other words, the number of times a task is completed on a particular day is proportional to the probability of finishing on that day.

One can therefore approximate the probability of finishing on a particular day by dividing the number of completions on that day by the total number of times the task was performed. So, for example, the probability of finishing task 1 on day 3 is 2/20 or 0.1 and the probability of finishing it on day 4 is 0.2.

It is straightforward to calculate the probability for each of the completion days. The tables displayed below show the calculated probabilities. The tables also show the cumulative probability – this is sum of all probabilities of completion prior to (and including) current completion day. This gives the probability of finishing by the particular day – that is, on that day or any day before it. This, rather than the probability, is typically what you want to know.

The cumulative probability has two useful properties

- It is an increasing function (that is, it increases as the completion day increases)

- It lies between 0 and 1

What this means is that if we pick any number between 0 and 1, we will be able to find the “completion day” corresponding to that number. Let’s try this for task one:

Say we pick 0.35. Since 0.35 lies between 0.3 and 0.75, it corresponds to a completion between day 4 and day 5. That is, the task will be completed by day 5. Indeed, any number picked between 0.3 and 0.75 will correspond to a completion by day 5.

Say we pick 0.79. Since 0.79 lies between 0.75 and 0.95, it corresponds to a completion between day 5 and day 6. That is, the task will be completed by day 6.

….and so on. It is easy to see that any random number between 0 and 1 corresponds to a specific completion day depending on which cumulative probability interval it lies in.

Let’s pick a thousand random numbers between 0 and 1 and find the corresponding completion days for each. It should be clear from what I have said so far that these correspond to 1000 simulations of task 1, consistent with the historical data that we have on the task.

We will do the simulations in Excel. You may want to download the workbook that accompanies this post and follow along.

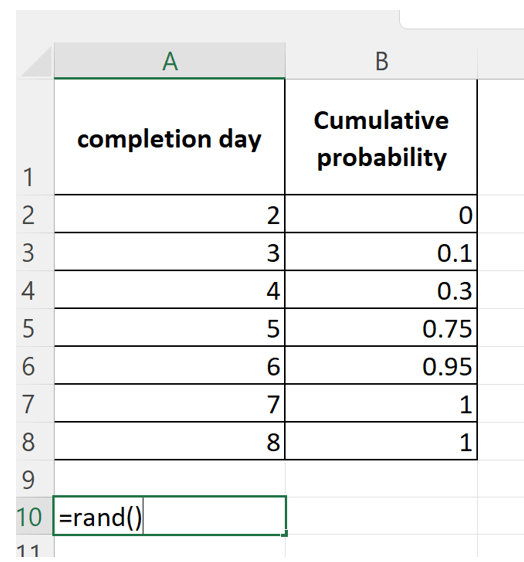

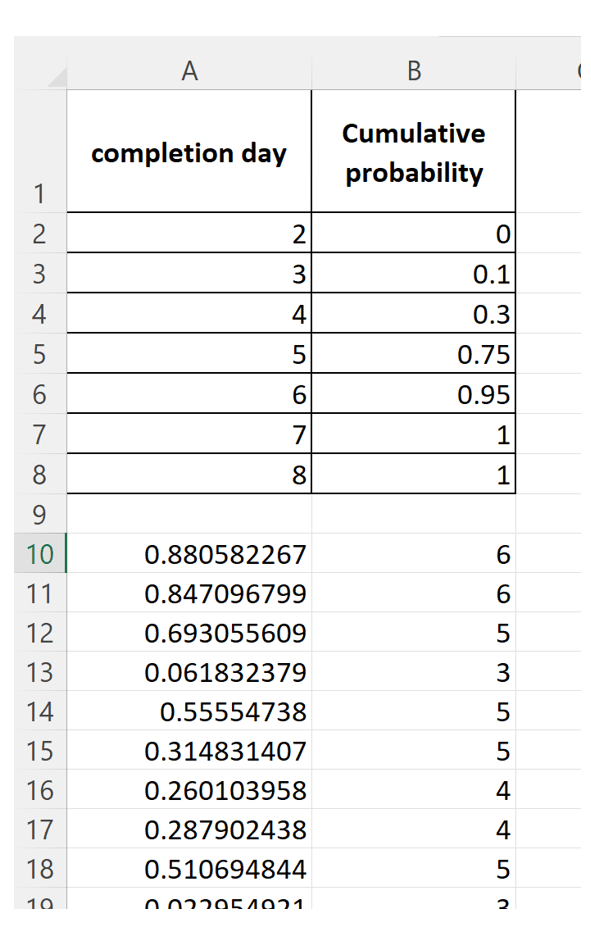

Enter the completion days and the cumulative probabilities corresponding to them in rows 1 through 8 of columns A and B as shown below.

Then enter the Excel RAND() function in cell A10 as shown in the figure below. This generates a random number between 0 and 1 (note that the random number you generate will be different from mine).

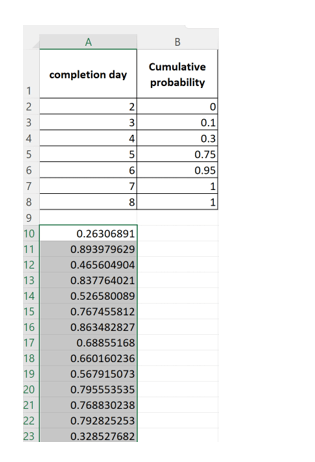

Next, fill down to cell A1009 to generate 1000 random numbers between 0 and 1 – see figure below ( again your random numbers will be different from mine)

Now in cell B10, input the formula shown below:

This nested IF() function checks which cumulative probability interval the random number lies in and returns the corresponding completion day. This is the completed by day corresponding to the inputted probability.

Fill this down to cell B1009. Your first few rows will look something like shown in the figure below:

You have now simulated Task 1 thousand times.

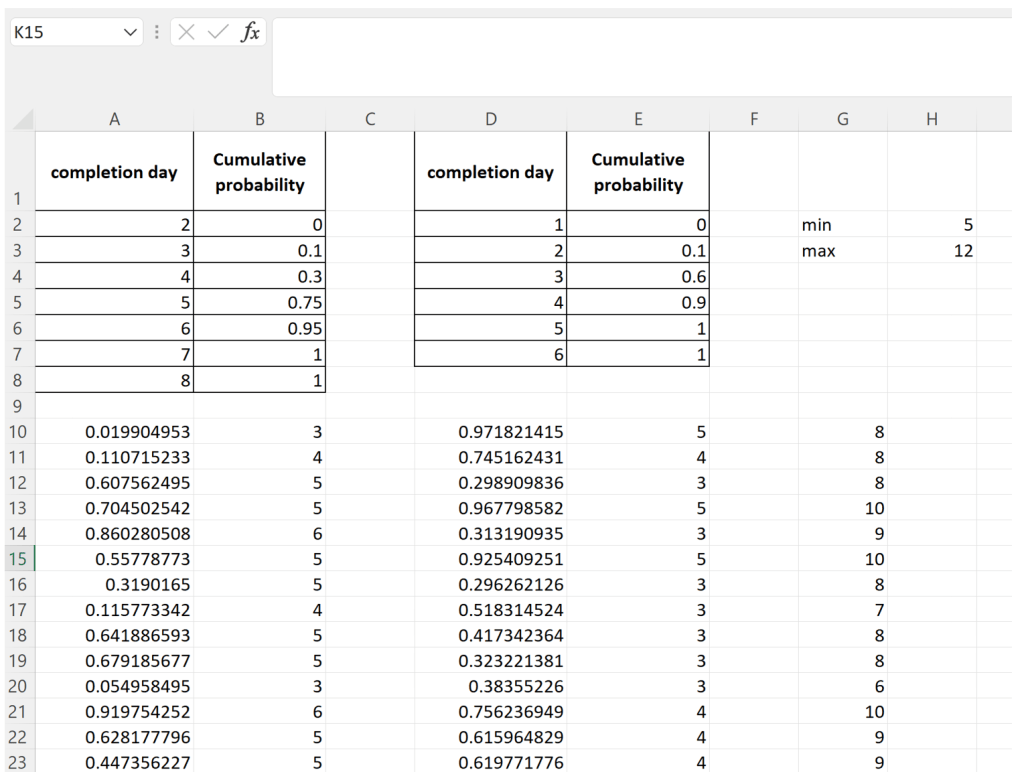

Next, enter the data for task 2 in columns D and E (from rows 1 through 7) and follow a similar procedure to simulate Task 2 thousand times. When you’re done, you will have something like what’s shown below (again, your random numbers and hence your completed by days will differ from mine):

Each line from row 10 to 1009 corresponds to a simulation of the project. So, this is equivalent to running the project 1000 times.

We can get completion times for each simulation by summing columns B and E, which will give us 1000 project completion times. Let’s do this in column G.

Using the MIN() and MAX() functions over the range G10:G1009, we see that the earliest and latest days for project completion are day 5 and day 12 respectively.

Using the simulation results, we can now get approximate cumulative probabilities for each of the possible completion days (i.e days 5 through 12).

Pause for a minute and have a think about how you would do this.

–x–

OK, so here’s how you would do it for day 5

Count the number of 5s in the range G10:G1009 using the COUNTIF() function. To estimate the probability of completion on day 5, divide this number by the total number of simulations.

To get the cumulative probability you would need to add in the probabilities for all prior completion days. However, since day 5 is the earliest possible completion day, there is no prior day.

Let’s do day 6

Count the number of 6s in the range G10:G1009 using the COUNTIF() function. To estimate the probability of completion on day 6, divide this number by the total number of simulations.

To get the cumulative probability you would need to add the estimated probability of completion for day 5 to the estimated probability of completion for day 6.

…and so on.

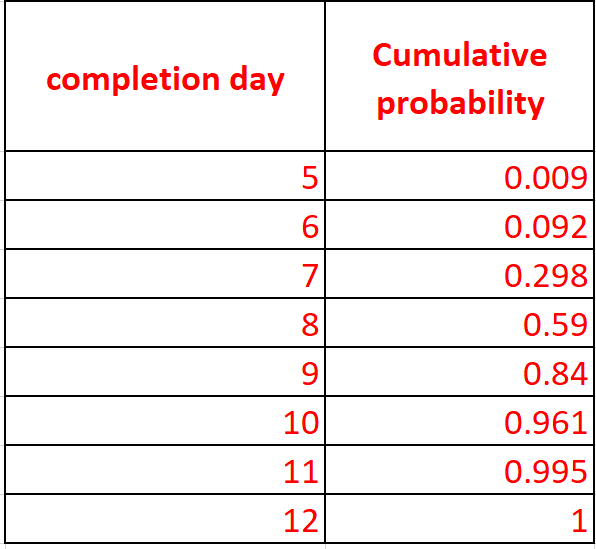

The resulting table, show below, is excerpted from columns J and K of the Excel workbook linked to above. Your numbers will differ (but hopefully by not too much) from the ones shown in the table.

Now that we have done all this work, we can make statements like:

- It is highly unlikely that we will finish before day 7.

- There’s an 80% chance that we will finish by day 9.

- There’s a 95% chance we’ll finish by day 10.

…and so on.

And that’s how Monte Carlo simulations work in the context of project estimation

Before we close, a word or two about data. The method we have used here assumes that you have detailed historical completion data for the tasks. However, you probably know from experience that it is rarely the case that you have this.

What do you do then?

Well, one can develop probability distributions based on subjective probabilities. Here’s how: ask the task performer for a best guess earliest, most likely and latest completion time. Based on these, one can construct triangular probability distributions that can be used in simulations. It would take me far too long to explain the procedure here so I’ll point you to an article instead.

And that’s it for this explainer. I hope it has given you a sense for how Monte Carlo simulations work.